DELETE: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age

Helen Lock reviews Viktor Mayer-Schönberger's analysis of the internet's influence over storage of our data

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, the author of Delete, is Oxford University's professor of Internet Governance and Regulation at the Oxford Internet Institute, so he should be well placed to comment on growing concerns about data and privacy online. But, nowadays I think this is a topic that everyone has an opinion on. In Delete, he documents how the ability of humans to retain information has developed over time and how the presence of the internet now has eroded the possibility of some information (that which appears on the net) of ever truly disappearing. It is an interesting book which benefits from taking a multidisciplinary approach to analysing the digital age, borrowing from history, law, anthropology, science and psychology to give us a comprehensive view.

I read this book out of curiosity and it lead me to be curious about a whole plethora of internet issues and also to a greater understanding of the internet's power. I had been using the internet (and technology in general) fairly blindly for some time and decided that I ought to start being more aware and stop being so frivolous. As a history student I was well-practiced at analysing the impact new technologies had on past society but I had been paying little attention to what has been going around me, to developments occurring in my lifetime. This sounds odd now I've written it but I think when you grow up with new technologies rapidly being invented and you don't have a strong practical interest in how it all works, this often means simply learning to use technology but not stopping to reflect on its cultural effects. Delete can be recommended because of its ability to do this without scare-mongering or being didactic.

Arguably young people should be more astute and knowledgeable about the internet than those who did not grow up with it. But as a teenager I think I was a perfect example of how many in my generation have reacted to technology. For example as a precedent to how I used the internet, I was careless with all my belongings; in one year I might have got through four mobile phones, two wallets and at least five keys. I also happily uploaded hundreds of photos to Facebook and Myspace, shopped online, bought tickets online and opened online banking as a student. I once spent £60 on gig tickets from a fake website, which made me realise I needed to be more careful purchasing online and I finally changed my privacy settings on Facebook when someone I no longer wished to be in contact with started messaging me and appeared to know everything about me. Neither of these incidents were grave or had dramatic repercussions, but not every internet user has been so lucky with their lack of care.

Mayer-Schönberger pivots his book on examples of times when the permanency of information on the internet has dramatically effected people's lives. He starts by talking about the case of Stacy Synder. She had just completed her teacher training in America, but was denied her qualification because of a photo she had posted on her Myspace page of her drinking at a fancy dress party. She was told that it was 'unprofessional' and 'might expose pupils to a photo of a teacher drinking alcohol'. Stacy was 25 and a mother of two, so was old enough and responsible enough to be drinking at a private party and was certainly drinking legally, but the damage was done.

Mayer-Schönberger argues that this example illustrates 'the importance of forgetting' and that this should be noticed now considering that humans have being trying to improve their ability to record and remember information for millennia. He argues that forgetting is not just individual behaviour, but there such a thing as 'societal' forgetting and this 'gives people who have failed a second chance.' He is also concerned about the psychological impact of such perfect memory, arguing that people who have naturally photographic memories find it hard to make decisions. He is concerned that totally comprehensive external digital memory may have a similar effect. When people are more aware of their past it tangles with the present, making it harder to move on, be decisive or have abstract thoughts.

Nowadays we quite regularly hear of cases where people using social media like Facebook and Twitter have embarrassed or incriminated themselves, or generally impeded their life, the most serious or humorous of which often get in to the news. Delete analyses a common, unsympathetic reaction to these cases, which is: No one should complain of the consequences when they have voluntarily made information public. This argument has intuitive logic to it, people are voluntarily putting information online, they probably should be aware of what that means. But is that fair? Delete asks the question, should everyone who discloses information lose control of that information forever and have no say about whether or when the internet forgets this information? And will the inability to forget lead to an inability to forgive? As more cases of information being misinterpreted and used against people appear, will people start to self-censor and therefore the original freedom of conversation facilitated by the internet could start to become more constrained? All of which makes for a very interesting debate.

In future, as our awareness grows, perhaps a code of conduct will develop over private and public definitions online. Internet education has developed far slower than the rate of how people use the internet has developed so perhaps this will improve too. Mayer-Schönberger offers potential solutions to the dilemma at the back of the book, such as negotiating expiry dates and perfect contextualisation (so making sure the context of comments and events are remembered to avoid confusion) which provide food for thought. At times the book is quite arduous, but it has moments of genius, and the validity and immediacy of the debate keeps you reading. After all the more information is shared and stored forever the more we need to adapt to this situation with clarity and understanding.

Image:

Review: The Revolution will be Digitised by Heather Brooke

Laura MacPhee follows the investigative journalist's account of the "Information War".

There is no doubt that 2011 has been a momentous year. The previously unimaginable scale and force of the Arab Spring has ensured that this will be viewed as a year of revolution. This is what makes the publication of Heather Brooke’s latest book so timely. The Revolution Will Be Digitised explores the role which technology has to play in the dissemination of information and the consequential empowerment of citizens.

Access to information has been a subject of contention for decades. Indeed, Radio 4 recently launched a successful programme entitled One Hundred Years of Secrecy which looked at how information has been controlled over the past century. So it is not the “Information War” that is new, but the battlefield, to extend that metaphor.

Much has been made of the role of technology, and social media in particular, in spreading information and encouraging democracy. Nonetheless, Brooke’s contribution to the debate is exceptionally valuable for a number of reasons, not least because she herself became integral to the plot in the process of researching it. As she explained at a meeting of Westminster Skeptics, she began this project as a detached and critical observer, before she realised how caught up she would become. This has allowed her to offer a unique insight into life on the front lines of the Information War.

This is not to say, of course, that the issue is exclusively a combative one. Heather Brooke speaks equally of the “Information Enlightenment” and explores the great opportunities available “where knowledge flows freely, beyond national boundaries”. The goal of this information exchange, she claims, is to discover “truths about the way we live, about politics and power.” Public confidence in each of these is so low that calls for greater transparency were almost inevitable. That is part of what makes The Revolution will be Digitised so appealing. Brooke adopts a narrative style, which makes the book especially engaging and accessible. This also allows her to explore the human stories behind the technological activity and political events. In the first chapter, she describes a young “kid” who becomes disillusioned whilst working in military intelligence in Iraq. This is a sympathetic tale which allows the reader to appreciate how someone in that position could be driven to leak secret information. Although he is not identified as Bradley Manning, Brooke acknowledges that there are distinct similarities.

She goes on to examine Manning’s plight explicitly in later chapters, but she achieves maximum impact by explaining the background first. She sets up the situation by introducing the phenomenon of hackerspaces. These are areas where technologically adept activists meet to experiment and explore the possibilities open to them. As Brooke explains: “Hackers want to deconstruct systems to figure out how they work.” This notion and its systematic implementation are vital to the progression of the book.

This is the story of the now infamous Collateral Murder footage, which shows a US Apache helicopter opening fire on Iraqi citizens. Brooke’s analysis takes us from Iceland (where public disenchantment with the banks sparked an appetite for transparency) to Norway, where she first encountered Julian Assange at a meeting of investigative journalists. She describes her relationship with Julian Assange in a way which reveals Assange in a strikingly intimate - and not altogether flattering - light. It is only after she explains how Assange chose to reveal and publicise the video footage that she introduces Manning’s arrest.

The plotline offers Brooke extensive scope to examine the opportunities and threats posed by the new channels open to both citizens and the government. She develops these points eloquently and reveals the complex and intricate web of rules which dictates how much the public know. Understanding how this works is just the first part of the process, as Brooke rightly points out. We must now figure out how to reduce the risk of censorship and maximise the benefits of increased openness. The potential gains are exceptional. As Brooke notes: “The greatest achievement isn’t in producing technology, but using it to re-define the boundaries of what is possible.”

Image: CC-BY-3.0 Heather Brooke The Revolution will be Digitised

Review: Barefoot into Cyberspace by Becky Hogge

Jonathan Kent celebrates Becky Hogge's personal journey through the chasms of cyberspace and beyond!

There’s a rule of thumb that ‘the more you know, the more you know you don’t know’ and there are few areas in which it’s stood me in better stead than in writing and broadcasting about the hacking scene. It was something I fell into as a reporter based in SE Asia. Back in 2004 I heard on the grapevine about a hacking conference taking place in Kuala Lumpur and arranged to interview the legendary Captain Crunch; John Draper.

In the early days hackers get-togethers were primarily a source of good stories, but over the years I’ve come to look forward to catching up with a hugely interesting collection of people some of whom have become good friends. And while I’ve come to realise how much I don’t know about the hacking scene I’ve also become acutely aware of just how much complete tosh is written about it by the media; even by tech journalists who really should know better.

Which is why (former ORG Executive Director) Becky Hogge’s new book ‘Barefoot into Cyberspace’ is all the more refreshing and indeed valuable.

Hogge takes us on something of a personal journey into the world of hacktivism in the company of such luminaries as 60s ‘Merry Prankster’ turned net pioneer Stewart Brand, Dutch hacktivist Rop Gonggrijp, Global Voices co-founder Ethan Zuckerman, author Cory Doctorow and Wikileaks frontman Julian Assange.

If there’s a theme running through the book it’s the clash between governmental and corporate interests on the one hand and the idealists who in great measure laid the foundations for the net we have today on the other. Starting and finishing her narrative at successive Chaos Computer Club annual congresses in Berlin, she touches on a range of issues such as copyright (and copyleft), personal privacy and surveillance, freedom of information, censorship and the commercial takeover of the net.

In and out of this she weaves another story; that of Wikileaks, whose travails through 2010 she watched from a ringside seat. If it has a fault, ‘Barefoot into Cyberspace’ doesn’t quite manage to tie all its themes together into a coherent whole. None of the issues that Hogge touches on are covered comprehensively. The focus is up close. Much of the book is reportage rather than a rounded survey of some big topics. However Hogge could fairly argue that it’s the most honest way to approach the subject.

Anyone, particularly any journalist, who claims to have an encompassing overview of hacktivism, let alone the wider hacking scene in its infinite variety, risks being 'called out'. I'm not persuaded that such an 'expert' exists. Hogge simply writes what she’s seen, recounts the conversations she’s had and tries to put them into some kind of context.

And it’s that context for which I am most grateful. Her account, much of it centring on Stewart Brand, of hacking’s (and to a great extent the Net’s) countercultural roots is an undertold story that explains this digital duality – part hippy idealism, part alternative, conflicted but voracious entrepreneurialism.

Frankly anyone who can build the movie Easy Rider into her story, quote Steppenwolf lyrics and name-check the great Enlightenment radical Tom Paine deserves to be read. Just as Paine grasped the great issues of liberty of his day, Hogge is tackling the great issues of liberty of ours and for anyone who cares about our freedom's future this is a must-read.

You can read Barefoot into Cyberspace by downloading it or by buying a paperback copy on Amazon.

Jonathan Kent is a professional troublemaker who has reported for the BBC, NPR, ABC, CBC, Newsweek, Reuters and the Daily Telegraph among others. He lives in Sussex, writes extensively about technology from a mildly tech-sceptic viewpoint, and is busy building a treehouse.

The Tunnel - reviewed

Jag Bahra reviews The Tunnel, a film you can watch for free on VODO that could revolutionise the way films are shared online

I was asked to review The Tunnel because of the groundbreaking approach that was taken in order to finance and market the film. A crowd-sourced model was used to raise the funds for the project - viewers may buy original film cells for $1 each. The film was released completely for free via bittorrent, and hosted on VODO – a free distribution platform for independent filmmakers. If you haven't checked out VODO yet you really should, they host some seriously quality content and it's all for free - you are encouraged to make a donation if you like what you see.

The Tunnel shows no signs of being a 'low budget' film. In this dark tale investigative journalist Natasha Warner becomes suspicious after government plans to renovate a network of disused underground tunnels are quietly abandoned. After hearing rumours of mysterious goings on and people going missing, it becomes clear that the government are hiding something. Determined to find out what is really going on, Natasha and her film crew break into the tunnels and investigate for themselves.

The film is presented via Blair Witch-style 'found footage' taken by the film crew in the tunnels - interspersed with documentary-style interviews with the lead characters. This unusual style makes for interesting viewing, helping to set the initial scene and then building tension gradually as the plot thickens. The underground setting is truly haunting and creates a dark, claustrophobic tone which is somewhat reminiscent of The Descent (2005). The air of eerie suspense soon descends into terrified chaos as the crew realise what is unfolding around them.

The acting is solid throughout, creating a genuinely human dynamic between the crew which conveys camaraderie and underlying resentment in equal measure. Particularly strong performances come from Steve Davis (Steve) and James Caitlin (homeless man Trevor).

As with all the best horror films, we never quite know what it is the characters are up against - the viewer only catches fleeting glimpses in the darkness. Whatever it is, the demonic adversary is cunning, sadistic, and master of its underground environment.

Horror fans should definitely give this a go. The Tunnel is nasty and gritty but with a subtlety that many big-budget Hollywood productions seem incapable of. Despite the inevitable comparisons with Blair Witch et al, The Tunnel is original, edgy and above all highly entertaining.

Download the torrent for free at http://vo.do/thetunnel . If you enjoy it, consider making a small donation (or even a large one) and help filmmakers to continue to make quality content. Progressive approaches like this could change attitudes to filesharing within the film industry.

Jag Bahra is a law graduate, civil liberties & copyleft enthusiast

Image: CC-AT-NC Flickr: Pro-Zak

Curtis over-simplifies in episode two of AWOBMOLG

Alasdair Thompson reviews episode two of Adam Curtis' 'All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace' and argues that Curtis over-reaches in his conclusions

An unrealistic view of nature as a self-regulating system, constantly in balance and which always returns swiftly to equilibrium after any disturbance has distracted us from a real examination of the structures of power in our society. Or so, at least, says Adam Curtis in part two of All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace.

Tracing a history that begins with the botanist Arthur Tansley and field marshal, prime minister of South Africa and designer of the League of Nations Jan Smuts, in the aftermath of World War 1, Curtis describes how we came to see nature as a system, an ecosystem, of energy flows and feedback loops that would maintain itself at a static equilibrium, where every part had its own place. A fantasy version of nature which could be drawn out, and even built, as circuit diagrams of feedback which we could measure and determine when to intervene to maintain balance.

Curtis shows how these ideas influenced and informed politics through the twentieth century; on the one hand it inspired a generation of lifestyle anarchists to believe in a self-organsing anti-politics, where they could cooperate as autonomous individuals, free from traditional forms of hierarchy, while on the other it provided an apparently scientific basis for power elites to maintain the status quo.

Smuts' holism saw every person as having their own place in society, as every animal and plant had their part in the ecosystem. Jay Forrester, a professor at MIT and founder of System Dynamics, thought he could map these systems of feedback loops and in the '70s, with the think-tank the Club of Rome, created a computer model that predicted imminent ecological collapse and led to the Club's neo-Malthusian Limits to Growth report.

But Forrester's work left out any space for politics. There were no feedback loops for changing the economic system. The system itself was taken as static, all we could do was alter the flows slightly within it, to intervene to restore balance. The environmental movement at the time said exactly that, and though Curtis notes this fact, he never investigates further what they proposed by way of alternative. It's a frustrating element of his work that he seems at times to pick an choose which movements and individuals to examine precisely in order to support his narrative.

He tells us that self-organised networks are incapable of dealing with power, but the only political examples he recounts are these which are avowedly apolitical. The hippy communes where politics was banned and no forms of collective organising were allowed, or the technocratic utopianism of Fuller or distopianism Forrester. If Curtis really wants to make the case that self-organised non-hierarchical organisation is unsuitable to take on power elites, he needs to engage with its political interpretations.

Towards the end of the programme he looks at the colour revolutions in Eastern Europe and criticises them for having no ideology beyond individual autonomy. Without an ideological underpinning there was nothing to support the revolutions and though the self-organising model was successful at overthrowing the old order, it had nothing to replace it with and was quickly replaced itself. Yanukovych is back in power in Ukraine and Georgia is less free now, in press terms at least, than it was before the revolution. In lacking an analysis of power the revolutions could not organise collectively to protect their newly won freedom.

Curtis ends by saying "[i]f we see ourselves as components in a system, it is very difficult to change the world. It is a very good way of organising things, even rebellions, but it offers no ideas on what comes next."

But that seems too simple a dismissal. Curtis is quite correct to say that without an ideological underpinning sustained change cannot happen, and that the lifestyle individualist anarchist idea of dropping out and building your own system independent of any power structure is impossible. But by failing to differentiate that there do exist non-hierarchical forms of organisation that recognise power and the need for collective organisation Curtis implies, by mistake or deliberate omission, that these forms are all equally useless for social change.

There's long been a tension in libertarian and anarchist thinking between a individualist autonomy and collectivist social freedom, but he ignores the history from Kropotkin, to the CNT-FAI to Bookchin and on to focus on individualism as the only outcome of non-hierarchy, and hence to reject the whole idea.

If all Curtis wants to say is that politics is important, that we don't live in a post-ideological age but that we are governed by very definite power structures and that we can only change them if we recognise their existence and organise collectively, then he should say that. By trying to tie in the organisational structure within which we challenge that power he undermines the more important point, and has earnt himself a lot of potentially unnecessary criticism.

A longer version of this article can be found on Bright Green from June 2nd

Alasdair Thompson is a PhD student at Edinburgh University. You can follow him at @agthompson

Image: CC-AT-NC Flickr: IsraelMFA

Review - All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

Alasdair Thompson reviews Adam Curtis' new series 'All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace'

If there was a fault with the first episode of Adam Curtis' All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, which aired Monday night, it was his analysis of the eponymous machines. In an hour long programme which was by turns brilliant, visionary, terrifying, and just a little frustrating, Curtis zipped from Ayn Rand's Objectivism to the New Economy bubble, the Credit Crunch and a barn full of people playing a collective game of Pong.

Curtis' thesis, that computers were meant to liberate us from traditional forms of hierarchy, government, and, if we believe Rand, the need even for altruism, but have instead provided false comfort and in fact helped to concentrate and consolidate power has some validity, and, as always, Curtis makes the case with considerable aplomb.

But it's not the computers themselves that made us slaves, it's the financial and governmental elites who utilised them. That might seem like a slight point, but Curtis' repeated claims that is was computers that created the financial models that failed, risks absolving those who wrote the programmes, interpreted (or misinterpreted) the results and failed to adequately manage or regulate their implementation.

The financial crisis wasn't caused by machines, it was caused by the greed and hubris of men. Of course, all that isn't to say that machines, and perhaps more importantly, our perception of what they could achieve, didn't play a significant role, and it's worth examining that in a little more detail.

Finance changed dramatically over the last thirty years. As markets were deregulated, and computing power increased, new assets into which money could flow were created. Securitisation became ever more complex and products more exotic. And as this happened new models were needed to keep track of all this information.

Managers, who still came from business rather than science backgrounds, began to believe that these new quantitative analysts could create models that would guarantee them profits they could only have dreamed of in the past. And behind all of this was the belief of the Objectivists that markets were rational and efficient.

The efficient market hypothesis (EBM) states, at its strongest, that all information about an asset is already in the price. What that means is that events that have already occurred cannot affect the future price of an asset, be that a share, a security or a piece of property. So if shares in a company have been increasing for the last month, that should have no bearing on what the price does tomorrow, because the events that led to those rises have already been taken into account.

So how does the EBM fit in financial modelling? Well, while the EBM says we can't simply extrapolate future prices from past prices it does tell us, formally, that asset prices should be what are known mathematically as Markov processes. That is they should be stochastic (random) processes where to predict (probabilistically) the future state of the system we need only know the current state, not the whole history of the price. This makes the maths much easier, and opens up the possibility of utilising decades of work in mathematics and physics to calculate the statistical properties of the market.

It makes it possible for complex financial models to put numbers on the risk of prices increasing or decreasing, and, hence, for traders to hedge against their transactions and, hopefully, eliminate those risks. If the EBM is right and the market behaves itself (there are no external shocks or crises) traders should be able to virtually guarantee not to lose money.

Of course the EBM isn't true. Markets are not efficient. A cursory examination of the historical data reveals that there is short term positive and long term negative correlation in prices. If a share has been increasing in price for a week, it probably will go up tomorrow, though only on average and to a small extent, while over a longer period it will revert back to the mean. Knowing when it is likely to switch is, unfortunately, almost impossible.

For all that, these failures only mattered so much because we believed them, because the regulators and managers, who often didn't understand the models or the risks, failed. If we blame the models, we risk thinking that if only we can get the model right, everything will be fine. In fact, the problem lies much deeper, in an economic and philosophical system that believes society can be perfected through rationality, that politics isn't important and if only markets were freer everything work itself out. If nothing else, the events of the last three years should have laid that belief to rest. Depressingly, they haven't.

A longer version of this article can be found on Bright Green from May 26th

Alasdair Thompson is a PhD student at Edinburgh University. You can follow him at @agthompson

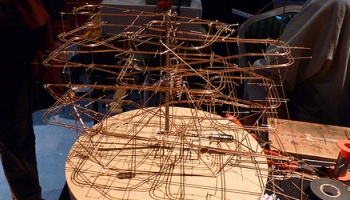

Maker Faire 2011

Milena Popova reports from the Maker Faire UK 2011 in Newcastle

Maker Faire UK is a two-day celebration of creativity, sharing and the pure joy of making things, which took over Newcastle’s two main science venues, the Centre for Life and the Discovery Museum, over the weekend of March 12th and 13th. It’s an event with a long tradition in the US, and this year saw its third UK incarnation.

This year’s fashion item were clearly 3D printers. You couldn’t move without bumping into one. We had 3D printers printing trinkets, 3D printers printing helicopters, and even 3D printers printing other 3D printers!

Once you got over that though, the other striking thing about Maker Faire was the sheer variety of exhibits. The Faire’s tagline lists 'robots, bicycles, cars, electronics, alternative energy, circuit boards, crafts, photography, synths, knitting, wood working', and I reckon there were a fair few other things there too.

Exhibitors ranged from commercial companies selling electronics kits and silicon goo, to people and groups who were purely there to share and showcase some of the cool stuff they had made. I asked Emily Toop, who was exhibiting some very cute miniature robots and other gadgets with partner Ian Ozsvald, why she was there. “In my day job, I’m a software developer,” she said. “It’s brilliant to be able to actually do something physical, make something that physically interacts with the world, like my robots. And it’s great to be able to show that off to the public.”

I spoke to Lizzie Taylor, contributor to the free online sharing community Instructables and inventor of the giant knitted Lego brick. I asked Lizzie what prompted her to share the patterns and instructions for her creations for free on the internet. Copyright, she said, was one factor: with something like a knitted Lego brick, selling it is not an option as Lego would probably come after you. There is less chance of that if you’re giving the pattern away for free.

Commercial viability was another - to make as much from her craft as she does from her day job, Lizzie would need to price her creations in a way that would put them out of reach of most people; the alternative would be to sell at a loss, which would undercut people who really make their living from craft, and she didn’t feel was fair. Ultimately, though, what Lizzie really hoped to do was to inspire others to make things.

I asked Martin, another Instructables contributor, how he got involved with maker culture. He started out making an external camera flash for his photography project. “It cost me about £2 in parts, or I could have bought it much more expensively from a shop. I wanted to share that with others, to show them how to make things cheaply and be creative.” He also thought it was important for people to understand how, for instance, their various gadgets and devices worked. “Once you’ve bought something, it should not be a black box to you, you should be able to understand it and retain control of it. I like enabling people to do that.”

Martin also introduced me to the magic of The Great Internet Migratory Box of Electronics Junk - a fantastic resource for makers of an electronics persuasion. It’s simple: you have a box, it’s full of electronics stuff; when you get it, you can take anything that you like and can use, and you can put components in that you no longer need. Then you send it on to the next person on the list. It’s a somewhat haphazard but at the same time inspiring way of obtaining parts for your projects - and generating new project ideas!

I also ran into the guys from London Hackspace who were doing all sorts of exciting things with the Kinect. Most of the projects they were showcasing at Maker Faire had actually been put together during the event, often collaborating with other exhibitors. Similarly to Martin, they too felt that it was important for people to be in control of their devices and not the other way round. Maybe that was why last I saw them, they were off to work on their Evil Genius Simulator, allowing them to control some quite impressive devices with the wave of a hand. (Go on, follow the link, you won’t regret it!)

Newcastle local Alistair MacDonald, inspired by the Live London Tube Map, has put together something similar for Tyneside Metro. Currently the project only runs on timetables rather than live data. Alistair is still hoping to get access to the live data from Nexus, following the success of the London version. “London Underground didn’t lose anything by making that data available,” he says, “but allowed a massive benefit for the public to be created. If we get the live data from Nexus, people will be able to take one look at the website and decide when to leave the house to catch the next metro.”

As the day was nearing its end and the Faire started winding down, I stopped at one final exhibit and met Stuart Childs from the Leeds-based Jam Jar Collective.

I asked him why he was at Maker Faire. “It’s the best event I attend!” he said. “You meet so many new and different people, there are the übergeeks showing off their projects, and families and the general public - those two groups would never normally mix! I meet lots of great people here, make friends and start off new projects with new collaborators.” Unlike most other exhibitors I met, who are either commercial or purely there for the fun of it, the Jam Jar Collective combine the two. Their creations - hardware, software, and art - are shared in an open and accessible way.

At the same time, they run paid-for workshops, take commissions, and sell DIY electronics kits. Stuart says, “When we work with clients, we make it very clear to them up front that we will want to openly share the design or source for whatever it is we make for them. Some are scared off by that, but then we probably wouldn’t want to work with them. It takes a while to get something like this to the point where it makes money, and I do often eat beans on toast for weeks on end, but I love being part of a community, sharing things, and being able to give back to the community too.”

I came away from Maker Faire cheerful and inspired. There are so many people out there not just making things but openly sharing, showing and teaching others how to do the same. The maker community is open and welcoming to anyone, so go find a fun project on Instructables or get yourself down to your nearest Hackspace and start making!

All photos courtesy of elmyra under Creative Commons license BY-NC-SA

Milena is an economics & politics graduate, an IT manager, and a campaigner for digital rights, electoral reform and women's rights. She tweets as @elmyra

Image: CC-AT-NC-SA Flickr: elmyra

New World Symphony: George Szell 1934

Czech composer Dvořák is a pretty easy to listen to, and there are plenty of recordings you can buy. His 1893 New World Symphony is one his best known.

The Symphony has a filmic sense of drama and tension. It’s well known and loved. The final act was famously lifted for Star Wars, and one of the best known tunes became popularised by HT Burleigh as a negro spiritual ‘Goin’ home’.

So why turn back to an old performance from 1934, apart from the fact it’s free? Well, I’m not an expert, but this recording seems to me to have extraordinary life and atmosphere. It really jumps out to me, despite the obvious technical flaws and imperfections.

There could be several reasons why. It might be due to the need in the 1930s to record in single takes. It may be that the conductor George Szell, a Hungarian, had a special feel for his music. It may be that as the recording was close to the period of the original composition – some forty years on – the performers were closer to the intended style, or perhaps to the optimism and fascination generated by the new American world.

On the other hand, it may simply be that the 1930s performance style is very engaging and strongly evocative of the many b-movie scores that were generated in imitation of composers like Dvořák down the line.

Take your pick.

Dvořák died in 1904, so his compositions have long been out of copyright. So older recordings of his works like this are entirely free from copyright restrictions, which means you can potentially use them for video remixes, mashups, whatever you like. The excellent archive.org has a digitized copy that you can download for free. You can buy the same recording from iTunes if you like.

Image: Carl Van Vechten

For nostalgia's sake

We may love them for what they once were, but Iman Qureshi argues that Radiohead's highly anticipated album fundamentally lacks heart

After much “is it Friday?” – “is it Saturday?” – “can I change my shift this late?” panic on the Twitterverse, Radiohead’s devotees were given a little treat: the new The King of Limbs album a day early.

So far there have been few grumbles of downloads stalling or people not being able to access the website – it seems Radiohead have got their techies in gear.

Now my Radiohead-heads, down to the nitty-gritty. The album kicks off with the underwhelming Bloom – but not to fret, the album that gave us Bulletproof, Black Star, Just, and Fake Plastic Trees began with the slightly clumsy anthem Planet Telex.

With its short plinky-plinky piano intro, quickly verging into the dubstep that is so familiar to Thom Yorke’s solo album Eraser, Bloom does not seem to settle into a clear course – an off-beat tempo, horns erratically thrown in and Yorke’s voice staying uncharacteristically apathetic for the most, it leaves something to be desired.

Never fear – coming to the album’s rescue is the gloriously angst-ridden and indignant Morning Mr Magpie. “You got some nerve coming here / You stole it all, give it back,” Yorke accuses sharply, while I punch fists in the air, delighted to hear again the bleak wry lyricism that keeps me falling in love with the band, time and time again.

And there is thankfully much more of that from the rest of the album, with the following Little by Little, featuring the catchy lyrics “little by little by hook or by crook” and “I’m such a tease and you’re such a flirt”.

But the slight momentum which the first half of the album picks up is soon shot by the redundant interlude Feral, which adds nothing to the development of the album. The ensuing single Lotus Flower thankfully pulls its weight, and provides an adequate relaunch after Feral’s downer.

This melodic poppy tune, together with the balladic Codex which follows, will be the album’s redeemer for many of Radiohead’s closeted Katy Perry fans – yes, I am one such. These two are without a doubt—and if twitter trends are anything to go by—the album’s climax. They give glimpses of what we so loved about In Rainbows.

But the thrills are short lived, and as the album ends with the sufficiently haunting but anti-climactic Give up The Ghost and the highly unmemorable finale Separator, I can’t helped but feel betrayed.

Perhaps the saddest fact about this album is that our investment in it—what we may like about it—is based on a nostalgic love. We hear remnants of Kid A or The Bends and are reminded of how these albums once blew our minds. Studio tricks and technical complexities it may have, but the album fundamentally lacks heart.

Radiohead, having continually presented us with new-fangled ways of playing and hearing music, have perhaps, dare I say, run out of ideas? And not only does the album offer nothing ‘new’, but nor does it elevate, shock or challenge. Being a perfectly pleasing album is The King of Limbs' very failure, and the strongest emotion I experienced while listening to this album, by far, was disappointment.

Iman Qureshi is a freelance journalist and currently editor of ORGZine. She tweets as @ImanQureshi.

Tweet-a-revolution?

It's roughly ten years since the “dot com bubble” collapsed, taking with it more than a few panglossian assumptions about the nature of online business. Now, according to Belarusian web critic and Foreign Policy contributing editor Evegny Morozov, we are seeing a re-run of that imbalance between expectation and reality. This time round, however, it is occurring in the minds of policy-makers, not investors

“How Not to Liberate the World” is an apt subheading for Morozov’s book – a critique of the growing trend in western foreign policy to put oodles of faith in the internet. The basic premise is that the western world's approach to promoting democracy among the oppressed has become mired in “the net delusion”. This, Morozov explains, is a false appreciation of the internet’s efficacy for spreading freedom, resulting in the over-promotion and over-use of technology for this purpose.

The titular net delusion starts with the assumption that the web has a strong propensity to effect positive change in authoritarian regimes – “cyber utopianism” as it is pithily coined. This leads to “internet centrism” – an over-reliance on the internet to achieve this end. Morozov lays out his argument over 12 chapters, subdivided into sections, all of which are highly readable. Although the book is largely a critique of a theory, the final chapter promotes an approach grounded in 'cyber-realism', but offers generalised suggestions, rather than definitive solutions.

The origin of the net delusion appears to be the end of the cold war, and Morozov makes a good case for the intellectual hangover of that era's global liberation paradigm polluting the mindset of modern statesmen and policy wonks alike. The Soviet Union collapsed, so it goes, when its people realised what a bad deal they were getting (via Radio Free Europe and samizdat propaganda). Information wot won it seems to have been the foregone conclusion, which now substantiates the utopian view of the web.

The influence and prevalence of this thinking is debatable, and Morozov encourages a re-assessment of our ideas on why authoritarian regimes fall. If our liberation blueprint is based on the fall of communism, and the reasons for that are misconceived, then we're in a precarious situation before the internet is even mentioned.

Our perception of authoritarian regimes is also called into question. Morozov suggests that we tend to see dictators as cartoon villains, appreciating their danger and brutality, yet simultaneously viewing them as bumbling Luddites. The resulting assumption is that Web 2.0 tools such as Facebook and Twitter will not be effectively appropriated by such regimes, who instead stick exclusively to the tried and tested tear gas and torture.

This is an important point in an era where we hail Facebook activists and Twitter revolutionaries. Are those who evangelise on these technologies—now including George W. Bush—“misunderestimating” a dictator's ability to utilise such resources as tools of oppression? Morozov makes the point that activists need to function in this section of the online world in order to be effective; however, this can pose huge risks when their authoritarian opponents can share the same level of access.

It is important to recognise that the real world power dynamic between individuals and corporations, activists and governments, does not shift as substantially as we might hope once that relationship is taken online. Consistently in my lifetime, as in Morozov's—we were both born in the 80s—popular culture has tossed up recurring examples of the archetypical lone hacker; confounding and defeating the techno-goliath (Wargames, The Net, Hackers, The Matrix, Tron, et. al.). The reality is that the established players (governments, multinationals, intelligence services) can and do achieve a significant strategic advantage online, which must be acknowledged.

The key point made is that the internet is a component, a facet, of the wider dynamic of authoritarian systems. It must therefore be viewed in a context unique to each environment in which we use it to promote freedom. Iran is not China, China is not Egypt, Syria is not the Soviet Union. To suggest that this is a new concept to all activists, NGOs and governments of all stripes, is patently false. Nonetheless, the risk that a “dot com bubble” style optimism prevails in our use of the web for liberation, as it did for prosperity, justifies a vigorous counterpoint.

The question, then, is: how deluded are we? Is the net delusion endemic in communities of activists, policy-makers and experts, or is there more to this then a cyber-utopian/cyber-realist axis? I would suggest that, as Morozov demonstrates the diversity of authoritarian applications of the web, he somewhat understates a similar diversity amongst those pushing the web as the key tool of reform.

Internet centrism and cuber-utopianism are useful as categories for some intellectual approaches, but they don't hold so well when used to categorise people. For some, the progressive power of the web is merely a sound-bite, rattled off with great conviction and little thought; for others it is the conclusion of years of analysis and critical thought.

That Creative Commons licensing is not a workable methodology for many content producers does not necessarily invalidate it altogether – it may just be waiting for its time. Likewise, the idea that the internet is central to the progressive political endeavour, and that it could significantly improve the balance of power in favour of the oppressed, could—and probably will—become more real in the next few decades. There is a risk here of condemning potentially useful concepts (and their proponents) on the basis of current utility. We should expect a more internet-centric future, although not necessarily a utopian one.

In “cyber-utopians”, one feels that Morozov has created a reductionist construct that best fits the unrealistic, intellectually lazy and generally ignorant mindset that he is opposing. Although I agree that this mindset does exist, and is prevalent in some areas, it only represents part of a wider picture.

The analysis is also somewhat selective and tends to drown the very real capabilities activists can gain from mass communication technologies. Again, the book provides a useful counterpoint in an ongoing debate, but should not be used as an alternate philosophy in itself – it's nowhere near broad enough. This might seem obvious, and I don't consider it to be the goal of the author; however, the debunking of myths should not be used to support an antithetical argument to cyber-utopianism, that the net is irrelevant and infective. We must instead use it to strengthen the debate, and in doing this, enhance our ability to see this technology through to its emancipatory potential.

Needless to say, believers in liberal democracy are not entitled to superior internet liberties. It can and does cut both ways, and as technology evolves, it will become harder to establish what the net (no pun intended) effects will be. We post links to WikiLeaks on our Facebook profiles, as Facebook, in turn, sells us to online advertisers. How do we interpret the risks and opportunities of such interactions?

If we fail to understand these risks, we will draw a distorted understanding of the political internet. Morozov's analysis, at the very least, can help guard against that. Failing to remedy unbridled optimism with effective debate could place the internet’s status as tool for liberation at the heart of an intellectual bubble, the bursting of which will hit more than just tech stocks.

Rich Millington is an amateur documentarian and a volunteer for the Open Rights Group. He has previously worked for ITV and Ofcom.

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.