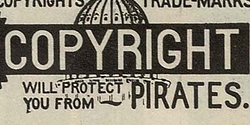

The long arm of copyright

Don't scroll down for more - all copyrights to content below the fold are reserved.

Image: CC-AT-SA Flickr: biwook (Ioan Sameli)

The High Court in England and Wales has just delivered a somewhat surprising judgement that sees copyright reach much further than many previously thought.

The case was brought by almost all major UK newspapers (besides News Corp titles and the FT) and their copyright licensing umbrella body, Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd (NLA ltd), against the users of a media monitoring service run by Meltwater Holding BV.

Meltwater operates a commercial site-scraping service that delivers newspaper headlines and the first few words of an article, according to keywords you give it. This helps keep track of your business' brand or your name as and when the media covers it.

Let's be clear: they aren't competing with newspapers for audiences using copyrighted content; this isn't destroying the newspapers' commercial incentive to write stories. Yet somewhat amazingly, the judge in the case held that under UK law, copying newspaper headlines is an activity that is in breach of copyright unless you are licensed to reproduce them or benefit from one of copyright's ever-shrinking exemptions. And weirdly, the judge seems to have ruled that this even applies to the copies created when you share, forward, commercially store ("in the course of business") or even open an email in your inbox.

Once upon a time, copyright used to only apply to substantial literary works, not short things like slogans or brand names. But according to the judge, under UK law, headlines are also protected. By the same logic, would reading a Metro headline aloud to your co-workers, or copy-pasting headlines into an email to a friend, make you a pirate unless you can rely on an exemption?

Worse still, it makes digital readers pirates. Incredibly, the judge in the case held that "the temporary copies exception is solely concerned with incidental and intermediate copying so that any copy which is ‘consumption of the work’, whether temporary or not, requires the permission of the copyright holder. A person making a copy of a webpage on his computer screen will not have a defence under s. 28A CDPA simply because he has been browsing."

On the point of whether scraping and/or caching websites without permission is an act in breach of copyright, the following was stated:

101. When an End User receives an email containing Meltwater News, a copy is made on the End User's computer and remains there until deleted. Further, when the End User views Meltwater News via Meltwater's website on screen, a copy is made on that computer.

102. Therefore the End User makes copies of the headline and the text extract in those two situations and there is prima facie [copyright] infringement.

103. When an End User clicks on a Link a copy of the article on the Publisher's website which appears on the website accessible via that Link is made on the End User's computer. (...) it seems to me that in principle copying by an End User without a licence through a direct Link is more likely than not to infringe copyright.

104. An End User who uses the share function to forward a headline Link (and, a fortiori, an End User who simply forwards an email) to a client will make further copies and thus further infringe. Such forwarding will also be issuing a copy to the public under s. 18 CDPA.

Previously, Google's caching of websites was covered by a copyright exception protecting temporary, incidental copies. Yet this judgement says that under UK copyright law, from the moment the content is "consumed" by a viewer/listener, a copy isn't incidental or temporary, and copyright is breached by a person using a digital device that "copied" the work to show/play it to to them:

111. The exception cannot be used to render lawful activities which would otherwise be unlawful. On the contrary, the purpose of Articles 2 and 3 is to ensure that copyright is protected against all forms of electronic copying unless falling within the narrow scope of the exceptions in Article 5.

Because I made it clear that I reserved all rights to this content at the beginning of this article, I'm afraid by bringing this sentence up on your monitor you are in fact in breach of UK copyright law, and a pirate, equivalent to a video or music pirate (see para 110 of the judgement). Unless you can rely on one of the other ever-diminishing exceptions, that is.

Needless to say, when the Government Minister for Intellectual Property, said "An IP system created in the era of paper and pen may not fit the age of broadband and satellites. We must ensure it meets the needs of the digital age" - when copyright now apparently applies to opening websites on your monitor, the upcoming review of copyright law is wholeheartedly welcomed. The last government granted rights-holders new rights to punish copyright infringement after its IP review. Let's see what this one does.

Now away with you, foul pirate.

Share this article

Comments

Comments (2)

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.

nigel salt:

Dec 16, 2010 at 04:31 PM

If enforced this would make a lot of RSS feeds either illegal themselves or illegal to read. Http links would have to have popup warning that you are breaking the law by following them. It is ridiculous.

Jim Killock:

Dec 16, 2010 at 04:56 PM

I guess the question is, how much attention will a judgement like this gain? Will it have a legal impact, or will the judge just find their judgement getting a lot of unexpected attention?