Three things I learned at the Turing Festival

Milena Popova condenses a weekend of talks at Turing Festival, Edinburgh's International Technology Festival in a report for ORGzine.

Governments are not in the business of defending freedom

To seasoned digital rights campaigners this is probably not news, but it’s definitely something worth reminding ourselves of. It was certainly a theme that ran through the “Freedom and Security” session at the Turing Festival in Edinburgh on Saturday morning.

Cambridge Security Engineering Professor Ross Anderson gave a bleak view of our rapidly eroding privacy and the Draft Communications Data Bill and its potential consequences. While in the 1990s and early 2000s we may have consoled ourselves with the option of encrypting our communications to protect ourselves from government intrusion, more recently cryptography has become less useful. With most of us now using services like Gmail or Facebook as our primary communication methods, it is no longer safe to assume that the endpoints of a message are controlled by the user. At the same time, anyone interested in the content of our communication can get the vast majority of what they need from so-called communications data - information about who we have communicated with, how, and when. The scope of the Draft Communications Data Bill is both vast and vague - a point also picked up on by ORG’s very own Jim Killock in his overview of the digital rights landscape. It may give the state unprecedented powers to automatically access our communications data from our Internet Service Providers, our mobile operators or even services such as Gmail, Yahoo and Facebook. As Professor Anderson rightly pointed out, we urgently need to have a national debate on whether we want an internal electronic surveillance agency and if so how we should structure and govern it. In the meantime though we need to continue the campaign against the draft bill, getting Labour, pro-civil-liberties Tory MPs and the Liberal Democrats on side. As Ross Anderson said, if the Lib Dems support this Bill then we need to ask ourselves what the Liberal Democrat party is for.

A similarly dire view of surveillance and government disregard for civil liberties in the digital space on the other side of the Atlantic was presented by the founder of the Calyx Institute Nicholas Merrill, who in the mid-2000s found himself having to challenge the constitutionality of parts of the US Patriot Act. Served with National Security Letter asking him to provide data on users of his ISP and banning him from speaking out about this, Mr Merrill sued the federal government which eventually led to the National Security Letters provisions of the Patriot Act being ruled unconstitutional. The lawsuit also exposed the extent of the issue: over the course of three to four years in the mid-2000s over 300,000 such letters were sent to US citizen. By conservative estimates at least one in every 1,000 Americans will have been affected by them. Outraged by the fact that most telecommunications companies will comply with government requests for user data, no questions asked, Nicholas Merrill is now working on a project to create an ISP with user privacy at the core.

As a media lawyer and New Statesman legal correspondent, David Allen Green’s view of both law making and the legal system is perhaps unsurprisingly cynical. To illustrate both the conspiracy and (in his words) the cock-up theory of law making, he took the audience through the history of the criminalisation of homosexuality in the UK, the Twitter Joke Trial as well as parts of the Communications Data Bill. Perhaps his most chilling comment also illustrates the key difference between the US and UK legal traditions: the UK, says Green, does not have a tradition of rights-based law. Where in the US you can challenge something like the Patriot Act for being unconstitutional, in the UK arguing a case on human rights grounds is “a sign to the judge that you are desperately waving a white flag”. This in turn makes David Allen Green’s call to action to all of us even more important: we increasingly have the tools to influence law making - from following the progress of a bill and various throw-away amendments with potentially disastrous unforeseen consequences through Parliament, to writing to our MPs and holding them accountable for their actions. We need to use those tools to ensure our rights are not infringed at the law making stage, as arguing them in court later is likely to be more difficult and less successful.

Your digital music, film and book collection dies with you

Dr Wendy Moncur from the School of Computing at the University of Dundee researches the intersections between technology and the milestones of our lives - including what happens to our complex digital lives when we die. Did you know that your Flickr account expires on death? Let’s hope your family has a back-up of all your lovely photos. Terms of service vary widely across the many digital services we use, and there is little in the way of legal framework to enable us to bequeath our digital assets to someone. Your family may not be aware of the existence of an account, may have problems proving that it was your account in the first place, or may find that once you put the content online you lost ownership of it. Depending on your needs, you may find that a digital executor or a digital estate service could be useful for you. None of these will help, however, when it comes to your digital content collections. The music, films and books you are giving Apple and Amazon hundreds of pounds for are often not your property and not a heritable asset. This is because you don’t actually purchase the content, but only a license to use it. Buyer beware.

The Raspberry Pi was created to solve a problem with Cambridge Computing Science admissions

Eben Upton, one of the creators of the Raspberry Pi was the highlight of the “Education and the Web” session on Saturday afternoon. Among the many revelations he shared with the audience was that, a passion for getting kids into coding aside, as a former Computing Science admissions tutor at Cambridge he had an ulterior motive for creating a small cheap piece of hardware that could be used to teach programming. Over the last decade, reports Mr Upton, both the number and the quality of applicants to Computing Science courses at Cambridge has fallen dramatically. Whereas in the late 1990s applicants would routinely come in able to program in Assembly language these days they are more likely to have done web pages. “And I don’t mean PHP,” Upton adds. “I mean HTML.” Ultimately, creating the Raspberry Pi was about countering the trend of having to make an active choice to code (as with pretty much every device since early dedicated games consoles and PCs) as opposed to having to make an active choice not to code (as with the BBC Micro and similar devices that kids in the 1980s grew up with).

The design principles behind the Raspberry Pi - cheap, robust, fun for things other than coding and bundled with every development tool under the sun - are pretty much the exact opposite to the design principles behind another piece of technology increasingly used in education - the iPad. While we may question the wisdom of giving £300 per device from the education budget to the world’s most valuable company, there is a trend in schools towards including iPads in classroom activity. Kate Ho from Tigerface Games shared some key insights on the use of the gadgets in schools - from basic concept reinforcement and numeracy and literacy practice for very young children to creating multimedia presentations in middle school. She also touched on the disadvantages of the iPad, including cost, pressure on parents to buy the devices and a reinforcement of privilege structures as an abundance of educational apps aimed at pre-school-age children gives those from wealthier backgrounds a head start.

Morna Simpson, founder of the education social network FlockEdu gave us a sneak preview of the future of adult education, and Jim Thompson, Managing Director of CogBooks gave us some insights into personalised adaptive learning A lively audience debate followed the “Education and the Web” session, where we talked about our wishlist for the new ICT curriculum, broadening the appeal of technology and other STEM subjects to a more diverse group of kids, and the renewed focus on adult education and lifelong learning that we need to see to equip our society with the skills necessary for this century.

Milena is an economics & politics graduate, an IT manager, and a campaigner for digital rights, electoral reform and women's rights. She is also a member of ORG's board and continues to write for the ORGzine in a personal capacity. She tweets as @elmyra

Image: Ross Anderson at Turing Festival CC-BY-SA Flickr: jimkillock

Murdoch –Up the Creek without a Paddle?

Following the News of the World scandal, Ibrahim Hasan offers a legal analysis of Sky News' hacking admittance

Is the Sky about to fall in on Rupert Murdoch?

On 1st May 2012, the Culture Committee delivered its report into the phone hacking scandal at the News of World. It questioned journalists and bosses at the now-closed News of the World, as well as police and lawyers for hacking victims. Its report has concluded that Mr Murdoch exhibited "wilful blindness" to what was going on in News Corporation and "is not a fit person to exercise the stewardship of a major international company.”

But it’s not just what went on at the News of the World which has caused concern. Another of the news outlets owned by the Murdoch empire stands accused of breaking the law in the pursuit of a good story. Where will it end? On 5th April 2012, Sky News admitted in a statement that it had hacked emails belonging to members of the public on two separate occasions.

One incident involved targeting the accounts of a suspected paedophile and his wife. The other one involved the “dead canoeist” John Darwin. His wife Anne collected more than £500,000 in life insurance payouts while he hid in their marital home. The pair were found guilty of the deception in 2008. In the run-up to the trial former Sky News managing editor Simon Cole agreed North of England correspondent Gerard Tubb could hack into Darwins’ Yahoo! email account. The full story can be read on the Guardian website.

The interesting aspect, from a legal perspective, is the legal repercussions for Sky News. It has stated:

“We stand by these actions as editorially justified and in the public interest.”

Note that it says editorially justified, not legally. As will be explained below, the offences involved do not contain a public interest defence.

Accessing a person’s computer (directly or remotely) without their consent to read their emails is a criminal offence under the Computer Misuse Act 1990 which is punishable with a fine or a term of imprisonment of up to 12 months. Section 1 (1) of the Act contains the elements of the offence:

(1) A person is guilty of an offence if—

(a) he causes a computer to perform any function with intent to secure access to any program or data held in any computer or to enable any such access to be secured ;

(b) the access he intends to secure or to enable to be secured is unauthorised;

and

(c) he knows at the time when he causes the computer to perform the function that that is the case.

There is no public interest defence in the Computer Misuse Act. However section 11 states that no proceedings can be brought for a section 1 offence more than three years after the commission of the offence. Darwin’s emails were accessed in 2008 and therefore a prosecution under S.1 is not possible.

Sky may also have committed a criminal offence under Section 1 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000(RIPA). Here there is not time limit for a prosecution. The Guardian reports:

“The broadcaster also published a voicemail message on its website, dated 19 May 2007, in which Anne Darwin is clearly heard leaving a message for her husband. The voicemail, part of an interactive graphic, ends with her saying “I’ll try and catch you tomorrow. Love you,” which the broadcaster said showed “she was doing as much of the running as he was”.”

Section 1 makes it a criminal offence to intercept a communication in the course of transmission. The listening to stored voicemails as well as accessing stored e mails all potentially fall into this category. The maximum penalty for such an offence is two years imprisonment. Again there is no public interest defence.

Once again this case bring into focus the highly dubious tactics of the media when trying to obtain information “in the public interest”. The setting up of the Leveson Inquiry and the inquiry by the House of Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sportmeant that at first the primary concern was about allegations of phone hacking by the News of the World. However it has now become clear that hacking phones was just one part of the unscrupulous journalist’s toolkit. It also included buying information from the police, blagging sensitive personal information from public and private sector organisations and the hacking politicians’ computers to gain access to their e mails.

There is now a very strong case for tougher regulation of the media especially when it comes to covert surveillance activities. My view is that, amongst other things, they should be subject to more of the RIPA regime as at present they only have to comply with certain aspects (Part 1 Chapter 1 – Interception of Communications). (read my blog for more).

This is a difficult time for the Murdochs and Sky News. The broadcaster’s parent company, BSkyB, is subject to a “fit and proper” investigation being conducted by the communications regulator, Ofcom, in the wake of the News of the World phone-hacking scandal. Cleveland police say that enquiries are ongoing into how the emails were obtained.

No doubt there is much more to come. As Kay Burley would say, “Stay with us…”

Ibrahim Hasan is a solicitor and director of Act Now Training which provides expert training in Data Protection, Freedom of Information and Surveillance Law.

Image: Rupert Murdoch - World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2009 CC-BY-SA World Economic Forum (Full Name) CC-BY-SA

Filters are not the answer

Jamie Bartlett, Head of the Violence and Extremism Programme at Demos, responds to the ORG / LSE Media Policy Project report 'Mobile Internet censorship'.

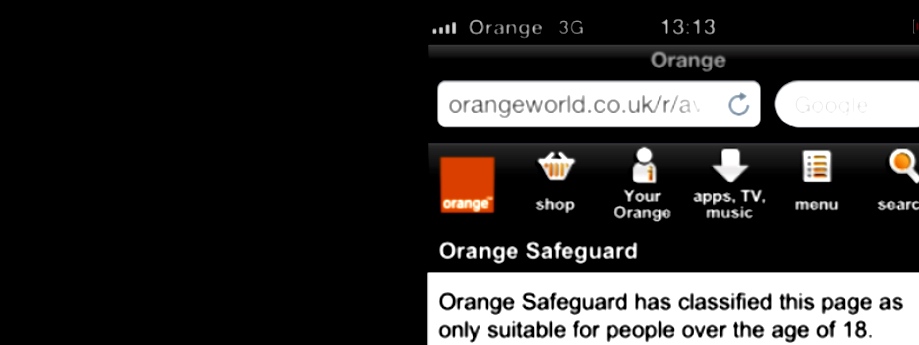

Today the Open Rights Group released a new report on default mobile internet filters. These filters are default blocks on certain sites set by Internet Service Providers, which prevent access to them.

Although the report is specifically about mobile filters, the broader argument is about internet censorship. Much of the debate about censorship comes down how we can protect children from inappropriate content - especially pornographic material - while maintaining internet freedom.

But as this new report argues, default internet filters are not a good way to tackle the problem. They tend to be unworkable, partly because the technology changes so fast. Because of linguistic and semantic problems, any default filters also result in legitimate sites being blocked.

I have a more fundamental problem with default filters and blocks. In an age of ubiquitous, accessible material, parents need to take greater responsibility for what and how their children consume online. As we argued in Truth, Lies and the Internet, there is much more on the internet to be concerned about than sexual content.

But parents think that the digital world is alien to them – a mysterious place inhabited by their digital native children. Rubbish. Parents need to become more familiar with various aspects of internet functionaility as part of their children’s general education; and impart the importance of critical thinking, and careful use.

Relinquishing this responsibility and handing it lazily over to ISPs, dulls the senses, and ultimately denudes us of our own duties. In the long-run, that will not help anyone.

This post originally appeared on the Demos blog. Jamie Bartlett is Head of the Violence and Extremism Programme at Demos.

Image:

Mobile Broadband Group response to ORG / LSE mobile censorship report

This is the first in a series of responses to the new report 'Mobile Internet censorship: what's happening and what to do about it', published today by Open Rights Group and LSE Media Policy Project.

How to offer appropriate protection to children on the Internet is a challenge that policy makers have been wrestling with for many years. It is necessary to navigate a path that does not unnecessarily restrict personal freedoms, is technically simple for customers to implement (or remove), can be executed via numerous distribution channels, across a range of devices, and can be applied with reasonable accuracy and consistency across hundreds of millions of web sites.

The mobile operators in the UK have been working in this field since 2002, when the first 3G mobile devices started to become available. In those times only a very small proportion of children accessed the Internet through their mobile device. In anticipation of significant growth in use by children, the UK’s mobile operators, under the auspices of the Mobile Broadband Group, published a code of practice in 2004, with a view to offering a safe browsing experience for children.

The Code has a number of elements. For the purposes of today’s discussion the most relevant relates to content available on the Internet, where operators have no control over what is available. A filter to the mobile operator’s Internet access service is therefore provided so that the content thus accessible can be restricted for children. The filter is set at a level that is intended to filter out content approximately equivalent to commercial content (Commercial content – means content provided by commercial content providers (encompassing own brand and third party providers) to their mobile customers) with a classification of 18, as determined by the Independent Mobile Classification Body, a body appointed by the operators under one of the commitments in the Code.

The Mobile Broadband Group Code has a strong claim to be one of the most successful in its field. The Code was the first of its kind and was used as the template for similar codes throughout the European Union. That said, child protection remains a very challenging policy area. It is not possible to achieve total perfection in a very dynamic environment – customers do not always have strong technical knowledge, children can be adept at finding ways round the protection systems and there are now supposed to be 644,275,754 active websites to classify.

There are no official benchmarks for classification accuracy. The BSI some years ago attempted to create a Publicly Available Standard for filtering systems, which required 99.99% filtering accuracy. If a ‘Six Sigma’ manufacturing standard were to be used a 99.99966% degree of accuracy would be required (in the context of 644m websites, 2,190 misclassified websites). Even allowing for the ORG missing a few, 60 misclassified websites does not amount to anything that could reasonably be described as ‘censorship’, particularly when mobile operators are happy to remove the filters when customers show they are over 18 and will re-classify websites when misclassifications are pointed out to them. This is how the small handful of web sites that get referred to mobile operators each year are already dealt with.

We believe that the vast majority of customers recognise the need for solutions in this area for the greater good – just as people are happy to show ID in off licences if they look under 25 (I would just be happy to be asked!).

In conclusion, I would like to emphasise the areas of agreement between the ORG and the MBG. The ORG agrees that giving safer access to children is a worthwhile goal. The MBG as well as the ORG would also like to see greater availability of filtering systems for mobile devices themselves – but the market is just not there yet. The MBG has also been working on a more comprehensive filtering framework for the mobile Internet and will announce developments on that front later in 2012.

The MBG will ensure that any misclassifications reported are corrected and will consider the ORG’s report carefully. We welcome stakeholder input from all points of view (and the ORG will be aware that many hold strong opposing views to theirs) and we will continue to develop appropriate child safety policy for an ever changing environment.

Hamish MacLeod is Chair of the Mobile Broadband Group. He is writing in response to the new report 'Mobile Internet censorship: what's happening and what to do about it', published today by Open Rights Group and LSE Media Policy Project.

Image:

The Wrong Number!

Ibrahim Hasan from Act Now offers an expert legal take on the new Government communications surveillance proposals

The Coalition Agreement states that the government "will end the storage of internet and e mail records without good reason." More recently Theresa May, the Home Secretary, when announcing the Protection of Freedoms Bill, said:

"The first duty of the state is the protection of its citizens, but this should never be an excuse for the government to intrude into peoples' private lives. Snooping on the contents of families' bins and security checking school-run mums are not necessary for public safety and this Bill will bring them to an end. I am bringing common sense back to public protection and freeing people to go about their daily lives without a fear that the state is monitoring them."

These pious commitments are now in tatters as, according to recent media reports, the Government wants the power to be able to monitor the calls, emails, texts and website visits of everyone in the UK. Whilst we are still waiting for the details, some have suggested that the proposals are directed not only at monitoring the use of new instant communication tools (e.g. Twitter, Blackberry Messenger etc.) but also at loosening the current restrictions on accessing communications data.

A new law, which may be announced in the forthcoming Queen's Speech in May, will require communications service providers (CSPs) to give intelligence agency, GCHQ, access to communications on demand, in real time. However it will not allow GCHQ to access the content of emails, calls or messages without a warrant. At present CSPs are obliged to keep details of users' web access, email and phone calls for 12 months, under the EU Data Retention Directive 2009. While they also keep a limited amount of other data on their own subscribers for billing and commercial purposes, the new law will require them to store a much bigger volume of third party data such as that from Google Mail, Twitter, Skype and Facebook that crosses their servers every day.

Civil liberties groups, including Liberty and Big Brother Watch, have condemned this move as an unacceptable invasion of privacy. This is not the first time this idea has been floated. In October 2010, the Government announced its intention to introduce the Interception Modernisation Programme (IMP), at a cost of £2billion. This was a rehash Labour's abandoned proposal (which was heavily criticised by the Coalition partners at the time) to require communications service providers (CSPs) to collect and store the traffic details of all internet and mobile phone use, initially in a central database. This latest announcement seems to be the same IMP project but renamed "the Communications Capabilities Development Programme (CCDP)".

The Law

Access to Communications Data in the UK is already governed by Part 1 Chapter 2 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) (sections 21-25). This sets out who can access what type of communications data and for what purposes. This includes the police and security services as well as councils, government departments and various quangos. The legislation restricts access to the different types of communications data depending on the nature of the body requesting it and the reason for doing so.

The definition of "communications data" includes information relating to the use of a communications service (e.g. telephone, internet and postal service) but does not include the contents of the communication itself. Such data is broadly split into three categories: "traffic data" i.e. where a communication was made from, to whom and when; "service data" i.e. the use made of the service by any person e.g. itemized telephone records; "subscriber data" i.e. any other information that is held or obtained by an operator on a person they provide a service to.

Some public bodies already get access to all types of communications data e.g. police, security service, ambulance service, customs and excise. Local authorities are restricted to subscriber and service use data and even then only where it is required for the purpose of preventing or detecting crime or preventing disorder.

At present access to communications data is granted through a system of self authorisation. There are forms to complete (signed by a senior officer) and tests of necessity and proportionality to satisfy. Notices have to be served on the CSP requesting the data. From time to time, the Interception of Communications Commissioner inspects public authorities that use these powers. There is no system of judicial oversight.

Real Time

It is unclear as to how the new proposals will be different from the current system. There is talk of the security services being able to access data in real time. The current system normally gives access to historic data. It does allow real time access to certain organisations (including the police and security services) but only in an emergency to save life or limb or in exceptionally urgent operations. The internal authorisation forms still have to be completed and written notices have to be served on the CSP later on. Maybe the Government wants GCHQ to have carte blanche direct access into CSPs systems. This would be unprecedented and certainly "Orwellian" to say the least. The potential for abuse would be massive.

Updating the Law

The Home Office Minister says they are updating the law "in terms of social media and new devices". If this means GCHQ knowing when an individual visits these sites, this is already allowed under the current regime known as traffic data (web browsing information). If the proposals go further and would allow GCHQ to look at actual webpages visited within a domain (e.g. Facebook) and calls made (e.g. from Skype) this would be a big extension of existing powers and much more intrusive. It gives the possibility of building up a picture of someone's lifestyle, their movements, contacts, interests etc.; potentially a vast amount of information which, if it gets into the wrong hands, can be quite damaging to individuals.

Safeguards

At present the checks and balances are very weak as discussed above (self authorisation followed by a notice to the CSP). The proposals, which talk of access in "real time" and "on demand", require much stronger checks and balances.

If it is really necessary for GCHQ to have access to such a vast amount of information, it should be subject to judicial approval. This could be a similar system to the one, which councils will be subject to as a result of the changes to the RIPA regime to be made by the Protection of Freedoms Bill. In the future any local authority request for communications data (however minor) will have to be approved by a Magistrate. (See my earlier article in LGL for more detail about the Bill.) After all, the powers that the police and intelligence agencies have under RIPA to undertake surveillance and acquire communications data are much wider than those of local authorities.

There are also legitimate concerns about what would happen if the information held and accessed on individuals by GCHQ gets into the wrong hands. Can we really trust the law enforcement agencies not to mishandle such data? Only recently allegations have surfaced that that the police have been misusing the same powers the Government is now seeking to extend, to assist the tabloids to locate the whereabouts of celebrities and other persons of interest.

The Government needs to think carefully before proceeding. If these new proposals are enacted there is a massive potential for misuse. They will provide a rich seem of information which may be bought by journalists from unscrupulous police and intelligence officers. This could lead to further erosion of public trust in the law enforcement agencies and Government. Of course "the Devil is in the detail" and we wait to see how the Government will address these concerns.

Ibrahim Hasan is a solicitor and director of Act Now Training. Act Now provides Expert Training in Data Protection, Freedom of Information and Surveillance Law.

Here comes the charge of the anti porn brigade

No-one learns about children's attitudes to sex by blocking porn; least of all politicians

Many of my old schoolfriends can barely remember any of their I.T lessons, let alone the 'Porn Incident' of Year Nine, when a small group of boys were found sharing pornographic images on school computers. It came as something of a surprise, mainly because everyone else knew not to do at school what they shouldn't even have been doing at home.

Anyway, they were caught one dreary afternoon and temporarily suspended for their misconduct. Then they came back. Everyone (nearly) forgot about it in the end. And eventually we all grew up.

But perhaps I've learnt the wrong lesson from this tale. Maybe I should be more alarmed at the ease with which pornographic material can be transferred, or that controls aren't automagically installed on school computers in order to prevent a repeat outcome.

At least this is impression I get from the report produced by Claire Perry MP and her merry band of porn blockers. The recent Independent Parliamentary Inquiry into Online Child Protection states that “six out of ten children can theoretically access the internet with no restrictions in their home”. In the hands of professional scaremongers this turns into Six out of ten children download adult material (yes, that's right; apparently 60% of kids have nothing better to do than stream smut onto their smartphones. When they're not rioting, of course).

But, in a bid to appease such moral panic, politicians will continue to search for the ultimate solution. The inquiry report suggests a network level “Opt-In” system emulating the one “already used by most major UK mobile phone companies”. Yet, it is not foolproof; see the infamous example of O2 blocking a church's website on the grounds that it featured adult content.

Internet Service Providers are rightly weary about the implementation of an überblock. TalkTalk have been bold enough to nudge new customers who wish to purchase their HomeSafe service into making an “Active Choice” over having adult content filtered on their behalf. But that is – and ought to be – the limit of an ISP's powers. Buying an internet package is not like ordering pizza. You can't have a no-frills version with the option of requesting some porn as a top-up.

As Professor Andy Phippen pointed out during the inquiry's oral sessions last year, the überblock is not the practical common sense solution Perry would have us believe. He said: “the vast majority of filtering technology is either metadata-based or keyword based”. So it cannot differentiate between sites that contain the words like 'sex' and sites specifically created for the purpose of displaying adult content. This raises the problem of false positives; filters will inevitably block the truths that may satisfy a child's curiosity over topics that refer to sex, such as anatomical biology, breast cancer, or sexual health.

The intention to adapt a combination of Ofcom and BBFC definitions of adult content for the web also neglects the fluidity of ratings systems. The 'TV watershed' has changed over the years, just as have ratings of many adult films. Both institutions revise their opinions more often than we think. It may turn out that their judgements on particular kinds of adult content may still be unpalatable for Perry and her porn-blocking posse, in whom Mary Whitehouse's spirit very much complains about video nasties, no doubt.

On a non-technical note, pornography is only one of a seemingly infinite number of things a parent has to worry about in raising their offspring. Never mind sex; children are just as easily at risk of discovering webpages portraying racially inappropriate or excessively violent content, or being bullied online.

And yet, according to the recent Ofcom media use and attitudes report, four-fifths (81%) of parents of five to fifteen year-olds trust their child to use the internet safely. 65% feel that its benefits outweigh the risks. Perhaps Claire Perry ought to trust parents to make the final call on their own kids' internet usage.

In my own school experience, porn took up very little time in the average boy's everyday life. Those who talked about it most probably had a stash to flog. But it meant nothing over the years, for porn rapidly gave way to texting and phoning girls, secretly hoping they'd return our advances soon enough for us not to fret over whether the feelings were mutual. That, or we'd go and play football.

Admittedly, this was at the tail-end of the dial-up era; mobile WAP technology was painfully slow and certainly not worth the cost. But I detest the notion that today's youth are sexually depraved porn-obsessed zombies, wandering about glued to their gadgets, getting xxx-rated content on the move without a care for anything else. What a way to insult their intelligence.

Porn or no porn, as social beings, children will inevitably be exposed to sex in ways that will fascinate and frighten them. There's no getting around that. If – like Andrea Leadsom MP – you still entertain the idea that “some sort of internet ISP network level security is the only answer that might potentially solve this once and for all”, then you will not have even begun to truly comprehend the innumerable factors underlying children's attitudes to sex.

The general – if slightly glib – opinion of the 'Porn Incident' at my school was that if the culprits were stupid enough to get caught, then they deserved the punishment they got. But then other more important things took over our lives and we all got over it.

Those with serious reality-fantasy anxieties directly affected by pornography ought to be examined and helped privately; there is no need to legislate for everyone else. But if there have to be any rules on internet usage at all, politicians should let parents set them. As one blogger so eloquently put it, child protection begins at home.

Habib Kadiri usually operates under the moniker of heakthephreak, mainly @heakthephreak.blogspot.co.uk.

Evidence of Anti-Piracy Three Strikes' Impact Mounting?

Don't mention the Digital Economy Act... Saskia Walzel looks at the impact of three strikes on legal sales

According to the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA) "The Evidence of Anti-Piracy's Impact Continues To Mount" and the impact of the French three strikes law is cited as example of how enforcement measures lead to an increase in legal digital music sales.

"Professor Brett Danaher (an Economist at Wellesley College) and colleagues recently did a study on the effects of a copyright alert system similar to the one announced in the United States last summer, that has been operating since 2010 in France (generally referred to as "HADOPI", see here, here, and here). Using data on iTunes sales in France, and other major European markets as comparisons, the study estimated that digital sales improved 22.5% for tracks and 25% for albums due to the enactment of and publicity surrounding the HADOPI graduated response anti-piracy laws. Further, the study found that sales increased even more strongly among the genres of music that were most often pirated (see Professor Danaher presenting his results here)."

The impact of Hadopi, the three strikes law which gets its name from the Government agency Haute Autorité pour la Diffusion des Œuvres et la Protection des Droits sur Internet, has been subject to numerous studies. Hadopi sent the first warning letter out 17 months ago and between October 2010 and December 2011 Hadopi has notified more than half a million internet subscribers that their connection is allegedly used for copyright infringement. 755,015 notifications were sent, and reportedly about 6 percent of internet subscribers in France were notified. No disconnections so far but Hadopi has for the first time passed the details of subscribers who have received multiple notifications to prosecutors in February this year. Subscribers could face a fine, or the disconnection of their internet access.

As always the impact of any given measure depends on how you look at it. In its own report, published earlier this month, Hadopi notes a decline in use of peer-to-peer filesharing networks in France, stating "benchmarking studies covering all of the sources available shows a clear downward trend in illegal P2P downloads." Hadopi does not pinpoint how much "peer-to-peer downloading" has declined following the implementation of Hadopi, instead quoting a range of surveys by third parties arriving at widely different results based on different methodologies. On the basis of various sources Hadopi concludes that the audience for legal music services, such as iTunes, remains overall stable. Spikes in use can be seen particularly in relation to Spotify, while the audience of iTunes only slightly increased. An increase in legal platforms across music, video and e-books in France is also noted.

The Hadopi report does not comment on revenues from legal music services in France, and whether those who have stopped filesharing because of Hadopi are indeed now paying for their iTunes. According to figures published by SNEP, the Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique, France's digital music industry grew by 25 percent to €110 million in 2011. Downloads generated €56 million of revenue, an 18.4 percent increase compared to 2010. Streaming and subscriptions grew by 73 percent to €39 million. Subscriptions services such as those from Spotify and Deezer grew by 89 percent to €26 million. Revenues from physical formats were down 11.5 percent to €412 million. Total revenues in 2011 were €617.2 million, down 3.9 percent from 2010.

How the long terms trend of increased digital music sales in France interacts with Hadopi remains unclear, nevertheless France is advanced as the poster child for the voluntary "six strikes" agreement which is about to go operational in the US. The fact that digital music sales are on the increase in countries which have not implemented three strikes is neglected. According to figures published by the BPI, the British Phonographic Industry association, digital music revenues grew by 24.7 percent in 2011 to £281.6 million, a third of record industry trade income in the UK. The BPI also reported a stronger growth in digital albums, which was up by 43.2 percent, and premium subscriptions, up by 47.5 percent. The BPI described the 3.4 percent decline in total recorded music trade revenues in 2011 to £795.4 million as "modest", with revenues from physical formats having fallen by 14.1 percent to £513.8 million in 2011. This is in line with long terms trends in the British recorded music market, but the music industry highlighted that growth in digital revenues now off sett two-thirds of the decline in income from physical sales. The BPI observed that:

"It is highly encouraging for the long-term prospects of the industry that the pace of digital growth continues to accelerate. British labels are supporting a wide range of innovative music services and music fans are embracing digital like never before. The record industry has continued to invest heavily in discovering and supporting outstanding British talent, which has helped sustain revenues in the face of difficult economic circumstances".

Without providing much context the Hadopi report concludes that in France "the wide range of legal content offers are gaining visibility and some offers have posted excellent progress. The labelling system for such offers opens up new opportunities and addresses a real need. Uneven and little-known, legal content offers show great potential for development, and it is important that far-reaching action be widely-undertaken and innovation put to use".

But it is unclear whether the increase in digital music revenues in France over the past 12 months would have happened anyway, or corresponds to the increase in legal content platforms. And whether revenues or awareness and use of legal services saw a boost since Hadopi went operational. Does the increase in digital music revenues in the UK suggest that France would have been better off without Hadopi, or that the US should focus on increasing the number of legal services and raising consumer awareness so as to increase revenues from digital.

France is the first country to actually implement three strikes laws, thus Hadopi's impact will be studied in detail in other countries where three strikes is being actively considered, such as Ireland, New Zealand, Australia, the UK and the US. Also missing is a cost benefit analysis for the Hadopi scheme. France looks to be one of the few instances where the taxpayer will contribute significantly towards the cost of three strikes with Hadopi reportedly having an annual budget of €11 million and employing 70 people. In New Zealand implementation of the three strikes law, which was rushed through parliament following the earthquake, has stalled because the music industry baulks at the possible cost, the proposed NZ$25 charge per notification being considered unviable.

In the UK the implementation of the Digital Economy Act is set to cost Ofcom some £5.8 million, with the annual cost being projected at £5 million. The cost of the appeals body that needs to be set up is yet unknown. The copyright owners using the scheme will pay most of that cost. But the UK has never established a proper economic impact assessment for the Digital Economy Act and it is unknown whether any increase in digital revenues that may be generated from three strikes would offset the cost of such a scheme. How many years it takes for three strikes to break even is not known either, but surely of interest to the music industry.

Hotfile in hotwater, Megaupload in the mire and a Hollywood hit list...

...but is the list fact or fantasy? Even Mediafire, a respected & transparent service, is caught in the crosshairs.

It’s certainly been a funny few months in filesharing that’s for sure! After years of relative calm, copyright agencies, film studios and major music labels, finally pounced on the new breed of filesharing technology, one-click filehosting sites, with the Megaupload indictment.

Sensing blood, copyright protection agencies, film studios and influential media professionals are now calling for more lawsuits to be brought against one-click filehosting services. It’s their contention that they’re a haven for pirated content. One of the most vocal is Hollywood honcho Alfred Perry. Last week he identified Depositfiles, Wupload, Fileserve, Mediafire and Putlocker as the key rogue sites on his target list. But was he right?

On some, Paramount Pictures Perry hits the bull’s-eye (Wupload) but on others he misses the target by a country mile (Mediafire). As Vice President of Content Protection at Paramount, he should surely know that Wupload & Mediafire are very different kinds of businesses?! So why has he lumped the two together in the same piracy pot?

If we look at Mediafire first, they’re a model of transparency and respectability. Search on Google for employee contact details and you’ll find them. Look on LinkedIn and you’ll find a company profile and personal pages for the key individuals including Tom Langridge.

Have they ever incentivised/paid people to upload content? Not at any point in their history (since 2006). They’re one of very few filehosting services that can boast this.

Then we come to their DMCA abuse process. And I can personally tell you it’s always been beyond reproach. Furthermore, they’ve fairly recently augmented their takedown tool and when Tom Langridge said last week “these enhancements have received rave reviews from organizations monitoring copyrighted content,” he wasn’t lying. I was one of them! Jodi Vest and the abuse team have always been an absolute joy to deal with.

So why have Mediafire been targeted? Well, there's the general mistaken view that all filehosting services are the same and this is simply not the case! It's highly likely that either Alfred Perry or someone else has seen Mediafire’s Alexa traffic stats and thought "hmmm, it's a file hosting service, it's got a lot of traffic so it must be bad and we therefore need to make an example of it!"

But isn’t this a worrying development? That not only a respectable business like Mediafire is caught in the crossfire but that key individuals in the piracy protection industry could appear to be so divorced from reality! Perry’s right about one thing however...

Wupload has to be one of the worst filehosting companies I’ve ever had to deal with as a Copyright Agent. They’re a highly secretive service ran by an anonymous parent company in the Far East. If you try searching for employee details, telephone numbers for key personnel or LinkedIn profiles, you’ll find nothing apart from suspicious pseudonyms (Willy at Wupload), ICQs and forename emails. So what have they got to hide and why are they so different to Mediafire?

It’s simple, for nearly a year, their business was largely based on unlicensed content distribution before they removed their affiliate schemes in November 2011 and very recently disabled all filesharing. Perhaps you think I’m jumping the gun? But consider this: When you provide monetary incentives for affiliates to upload content (in Wupload’s case - $40 for 1,000 downloads), it’s highly likely that it’ll be popular Copyrighted movies, music & pornography.

Some people have made a lot of money out of sharing unlicensed content. Just look at the following posts on WJunction! MaX Has earned nearly $30,000 from Filesonic (Wupload’s parent company), deejam007 earned $18,200 from Filesonic & Wupload, stevvva earned $21,000 from Filesonic in 6 months, fewcent earned $32,000 from Hotfile, djkelaj earned $50,000 plus from Filesonic in less than 6 months & another uploader earned over $8,000 from Oron in 3 months. What do they all have in common? They uploaded unlicensed content. And if this is what some uploaders are paid, how much are the people running these sites making?! You only have to look at Kim Dotcom as an example.

This is exacerbated by the fact that Willy (supposedly Wupload’s CEO) often congratulated uploaders on their earnings and seemed publically blasé about DMCA Notifications. But why? You have to understand that Wupload etc pay affiliates to upload popular/often pirated content in order to change free downloaders (capped download speeds, no parallel downloads) into premium paying members (no limitations on the service). That’s how they make their money.

Hence, while Wupload and other cash for upload hosters will pay lip service to Copyright/DMCA laws by deleting files, it’s not in their interests to remove profitable affiliates as they help drive a lot of traffic/money to the site. It’s always the same scenes/people that upload billions of files yet little was done to stop them. To do so would be commercial suicide.

The above therefore explains why my experiences of Wupload’s abuse department weren’t good at all. For most of August/early September 2011, Wupload frustrated all legitimate removal attempts and made close to 50 misrepresentations to me and my clients’ that they had deleted content when they hadn’t.

As a consequence of their recalcitrant attitude, we had to report Wupload to their upstream provider (on over 10 separate occasions!), WebaZilla, and the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) before they begrudgingly provided administrative access. I can report that the IFPI and other agencies had similar problems with them too hence the reason they were on a piracy list back in September 2011. This has been a long time coming!

But what about the other services on the target list? Whilst Fileserve are nowhere near as bad, they still incentivised uploads of pirated content by paying uploaders and did little to delete repeat infringers. It’s also another company that’s highly anonymous, uses pseudonyms (Ricky is the CEO allegedly!) and has no proper contact details for employees. Ask yourself this question: If Fileserve can self delete billions of files, thousands of affiliates in the aftermath of Megaupload, why hadn’t they policed their servers sooner? The answer: they simply didn’t want to as it’d damage their business.

Depositfiles also pay cash to uploaders. They’ve been around since 2005 and are somewhat secretive but to a lesser degree than Wupload/Filesonic and Fileserve. In addition, whilst content is always deleted extremely quickly, they could do more to remove repeat offenders. Their inclusion on the hit list is thus debatable.

I must confess to not having much experience with Putlocker as my clients’ content rarely appears on there. However, I can report that they delete content promptly.

But what’s the situation now that Wupload/Filesonic & Fileserve have closed? Putlocker operations officer Adrian Petroff proclaims: “Who needs SOPA when a studio exec can make a wish/hit list and sites ‘voluntarily’ shut down?” But is that true? In all honesty, it’s somewhat misleading. In fact, Petroff should be doing his best to distance himself from some of the other services on the list.

Wupload, Filesonic & Fileserve all voluntarily shut down because they collectively have a lot to hide. They incentivised uploads, did little to delete repeat infringers, in some cases had a very lackadaisical attitude towards Copyright infringement and now that they have made their money, want to run off anonymously into the sunset. That’s the real reason for their disappearance. Will it catch up with them? Who knows but it’ll be interesting to watch!

James Brandes is a Copyright Agent who operates the Digital Copyright Consultancy. The Digital Copyright Consultancy provides anti-piracy protection for a wide variety of clients' in the music and adult entertainment industries. It has worked on 3,000 + assignments for over 60 clients'. Projects have ranged from providing piracy protection services for Digital EP releases to well known dance compilations/rock albums and adult DVD releases/website content. He tweets @DigCopyright

Image:

Oi! Lib Dems! Are you listening?

There's no use in bugging us if you aren't going to listen to what we have to say

This is a shout out to the yellow half of the coalition government. The so-called liberal contingent who claim to defend individual freedoms against state oppression.

What is so liberal about the proposals to track all internet-based correspondence? Whose liberty is most at stake here? That of suspected criminals, or the innocent everyday user?

What kind of precedent do you think will be set by this law? You may think the monitoring of all online communications will be restricted to whos whens and wheres, but can you prove that every subsequent government will have the same restraint over what is being said between non-suspects?

You may think that the proposals are merely "updating the rules which currently apply to mobile telephone calls to allow the police and security services to go after terrorists and serious criminals".

In that case, will you also be in favour of extending the DNA database to the entire population? Or having Royal Mail screen all physical correspondence? Or tagging all walkers?

It may sound ridiculous, but the principle is surely the same: no longer will reasonable suspicion be necessary for the state to stalk us. And if it can, it will. Is this part of your idea of a liberal justice system?

You may think that the storage of such data is ok because it will not be handled centrally by government. But you instead propose to outsource this responsibility to the private interests of Internet Service Providers. To what end? ISP are already instructed under an EU directive to keep details of users' web access, email and internet phone calls for 12 months. This is in addition to the copious quantities of data mined and retained for commercial purposes by internet companies as well. An unholy alliance is potentially afoot; intelligence services already have access to more data than ever before... it just happens to be gathered by the private sector. And they'd only need ask for it.

Do you remember what you declared in your own 2010 manifesto [p94], then pledged in the Coalition agreement [p11]?

So, is this your idea of defending our civil liberties? Free and open access to personal data for businesses, paid for in personal freedoms, all at the request [with or without a warrant] of a panopticon state?

You've been clamouring for recognition of the positive influence you have on this government's policies for some time now. If there was ever a time to prove your worth to the UK electorate, now is it. Please stop these plans from becoming reality, before it's too late.

Habib Kadiri usually operates under the moniker of heakthephreak, mainly @heakthephreak.blogspot.co.uk.

Image:

Is ACTA dead?

ACTA may have been put to rest for now, but it could strike back at any time

"Is ACTA dead?" It is a question often heard, or even a fact stated. And despite the impact of mass protests and the recent turns of events, it ain't over till it's over. ACTA may be in a coma, following a legal check at Europe's highest Court. However, the patient may have been brought back to life this week when the European Parliament voted against it's own referral to the same court. What factors contribute to ACTA's diagnosis?

Protests in all major European cities and hundreds of thousands of concerned emails to Members of the European Parliament have raised awareness among politicians that ACTA causes many essential concerns. Some happily declared ACTA dead after the significant loss of support in Brussels and the Member State governments.

The European Commission has attempted to resuscitate ACTA by referring the controversial agreement to the Court of Justice of the EU for a legal check. Shortly after, David Martin, the newly appointed MEP responsible for the ACTA dossier, announced that the European Parliament would be asking its own questions to the European Court of Justice. This course of action was blocked by a majority in the leading committee of the European Parliament this week.

"I regret that the European Commission tries to regain control of the process by sending ACTA to the Court for a legal check. Earlier, the European Parliament's request for such a check was disregarded", liberal MEP Marietje Schaake noted. "It is unsure whether the request for a legal opinion suspends the ratification process, but the European Parliament's committees will now resume their work on formulating opinions on ACTA, and vote on the controversial agreement in June."

The responsible committees of the Parliament are continuing their work on drafting opinions in the fields of their competencies. However, the fate of ACTA seems bleak at the moment.

Bulgarian MEP Ivailo Kalfin speaks for many when he said that the ACTA agreement is ill fated, since it concerns many people around the globe but the text was drafted in secrecy, without taking into consideration the stakeholder's opinions and by bypassing the legitimate international bodies. As a result the text contains many structural deficiencies and contradicts with well established practices and principles in the internet space.

Dutch MEP Marietje Schaake is also particularly concerned with the mix of issues ACTA tries to regulate. "The European Commission is regulating counterfeit (physical, tangible) goods and the use of (digitized, intangible) works online with the same remedies. Digital media sharing should not be enforced the same way as trade in fake medicines and other dangerous goods being produced by organized criminal networks. Considering the theft of products from shops equal to sharing music files shows an alarming lack of understanding of the digital age. All the talk of enforcement would almost make us forget the tremendous opportunities of bringing content to audiences at lower prices, thanks to the digital revolution. We must ensure our fragmented copyright laws or ACTA do not hamper Europe´s digital market, or our competitive position in the global economy."

MEPs Schaake and Kalfin agree that whatever the opinion of the ECJ, the European Parliament has serious reasons to diagnose ACTA as the wrong medicine for many different diseases. "It is not about compliance with the EU acquis, it is about the future of the Internet and the ability of the EU to protect intellectual property rights without hampering internet freedom and the technological development", Ivailo Kalfin concluded.

ACTA is not dead, and a lot of work continues to be done. It is unsure whether ACTA is currently in a coma, but sooner or later the European Parliamentarians will likely cast their decisive vote in June. Those who want to help raise concerns, please do so with the accuracy of a CT scan, and the precision of a surgeon. Misinformation in the anti-ACTA lobby has cost a lot of credibility.

MEP's Kalfin and Schaake will be organising a stakeholder hearing about ACTA on April 11th from 13.00 - 15.00. Several organisations that have been critical about ACTA will come to explain their reasons for opposing the treaty. You can follow the proceedings online, or register to attend the event by mailing marietje.schaake-officeuroparl.europa.eu.

Image: By ottodv (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.