To filter, or not to filter...

Stephen McLeod asks, do the same rules of engagement apply with relation to the internet?

Image: Illustration by Nadine Khatib

Remember the advice that adults used to give young people about using the Internet, back when it came from the mouths of 'experts' such as the illustrious Carol Vorderman?

'Never give out your real name online'

'Never give out your e-mail address to a stranger'

'Never send your photograph to anybody you don't know'

Whilst this advice seems laughable in the infinitely connected world of 2013 (well, to most of us anyway, this can still be found on some Government websites), it was just as ridiculous back then - especially to those of us who were the last generation to grow up without having the Internet wired into our everyday interactions. As we took to discovering the best ways to navigate this brave new digital frontier on ridiculous 28k dial-up modems, it was already clear that adults simply did not understand the way that things online worked.

Can you imagine the reaction from a parent 10 years ago, had their child had come running into the living room, exclaiming:

'Mum! Dad! Somebody said nasty things to me on the Internet.'?

Probably not.

For those of us who have been online for a long time, it can seem bizarrely naive that anybody would expect to come online and not expect to be the subject of any abuse. The culture of the Internet has long since been about stirring up reactions. Everywhere you look, users are playing devil's advocate; purposefully asking divisive questions; and criticising statements from every angle to such an extent that nobody can be sure whether anybody is actually being serious about anything anymore.

…and that's the beauty of it; the Internet is serious business after all. The architecture of the web, and the ability to be anonymous or employ multiple identities all at once forces us to confront the inconsistencies in our own positions; challenges how we react to others who disagree with us; and highlights hidden prejudices. It is the ultimate playground for deconstructivist postmodernism.

Young people who have discovered the deepest corners of the Internet long before their parents have had to confront all of this chaotic and often contradictory approach to the way people communicate purely off of their own backs. Many have had to subconsciously develop sophisticated ways of dealing with a medium which is complex and often aggressively confrontational. The relative ease of this process for these generations isn't something that we should be too surprised about. How many of you are aware of what it's actually like to be a high-school student in recent years? Some of the things said by teenagers in 'playgrounds' across the country would raise more shock and consternation than the tweets that increasingly garner outraged national media attention.

As the discussions in recent weeks have illustrated, those who are most vocal on these topics have still simply failed to understand the fundamental fact that the same old rules of engagement do not apply when it comes to the Internet - or at least, not with regards to their application. Just as we know and learn how to deal with the sliding scale of what is appropriate in 'real life' situations with people we find undesirable, we have to adapt to the environment of the Internet. Whilst there are undoubtedly threats that should be taken seriously, we must also recognise that not all messages which appear alarming are created equal, nor should warrant the same level of response. How we deal with abuse online will unquestionably require the law to respond to some degree (with all of the jurisdictional restrictions and complications which that brings), but it is necessarily eventually a social and cultural question rather than a legal one.

Instead of looking to implement restrictive legal remedies against the providers of platforms which allow the anonymous transmission or exchange of information, we must ensure that both ourselves and our young people are properly equipped to handle the realities of this world that they arguably know a lot more about than the majority of their seniors. We have to stop patronising them by making out that we know better than them about how to survive in every given difficult situation they will encounter, just as we don't interfere in every interaction they have whilst amongst their friends at school.

Let's also bear in mind just how contradictory the advice that's been given over the years about how to be safe online has actually been - moving from a position of keeping your identity anonymous as we've seen in the opening paragraphs, to one where instead now we are apparently actively calling for networks like Twitter to verify everybody against their real name and address so that we can find out who the perpetrators are… or... something.

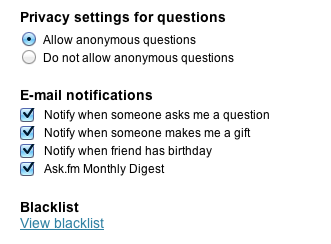

The recent media flurry around the deaths of young people after receiving abusive anonymous messages on platforms such as Ask.FM has caused the oh-so-predictable misinformed knee-jerk reactions that have come to characterise what we might expect, and just reinforces to young folk again that adults really don't have a clue what they are talking about. What I haven't seen mentioned in a single one of the reports concerning the 'responsibility of online providers to prevent anonymous abuse on their systems' is the fact that users actively consent to questions from anonymous users. Tumblr does it. Ask.FM does it. Formspring.me does it. All of these services provide a simple way for people to avoid getting exactly the sort of messages that they are being charged with responsibility for.

In some places (such as Twitter) this might not be as easy a process as people who are high profile (and thus naturally receive a higher volume of interactions) may like, but this is certainly not the case when it comes to the likes of Ask.FM. Not only can you choose to never receive anonymous messages, but you also have an additional blacklist for specific users you might want to filter out. See this screenshot of their settings panel:

We must be careful not to confuse the issues of one circumstance with another.

The real question that we should be asking is not how to find a legal redress against networks (read: The entire Internet) for providing people with an anonymous way to communicate, but why when given the choice to opt out of interactions from people that don't identify themselves, people choose to continue to receive them… even when that includes abusive messages. The feature itself is often used so that people can send Valentines-esque messages in a secret admirer type fashion, and so in reality it often comes down to questions about insecurity, self-esteem, and how people want to be seen by others. Shouldn't we perhaps be concentrating on this instead, and how best to help our young folk deal with these sorts of issues, instead of leaving them to work it out on their own…?

Whatever the answer is, it isn't to point the finger of blame at the Internet.

Stephen Blythe is an internet law geek with an LLM on the way, and Digital Marketing Manager for tech firm Amor Group. You can find him on Twitter, and Google+.

Illustration by Nadine Khatib

Share this article

Comments

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.

Comments (0)