A social-networking success story

The Voices for the Library story demonstrates how effective social media can be for promotion on a massive scale, collaboration between geographically diverse team members, and giving a voice to people who would otherwise go unheard

Voices for the Library is a campaign group promoting the value of public libraries. The team behind the group live in different places. They have only met face-to-face once. Despite this, they have worked together for the past five months to create one of the most well-known library campaign groups in the country. The group owe its existence and its success to social media tools.

The group began on Twitter. During the summer of 2010, a media narrative developed claiming that libraries were failing and that the internet was replacing the need for libraries and trained library staff: these assertions are not true. This reached a nadir when BBC’s Newsnight mistakenly reported that the total number of loans from the UK’s public libraries in 2006-2007 was 314,000: the actual number is approximately 314 million.

The library community has a very active presence on Twitter—over 400 library workers use Twitter regularly—and soon, a small group of librarians began to share ideas about how to counteract traditional media’s misrepresentation of libraries. By September, Voices for the Library was set up: a platform to spread information about libraries and let users share their stories about the value of libraries.

As a team of volunteers spread across the UK with no budget, we relied on our technical knowledge and expertise to promote ourselves using free and functional social media tools. Within three weeks, we were using Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, Delicious, and a website built on WordPress to spread the word and gather supporters. We now regularly use these as platforms for spreading information about local campaigns, events across the country, the latest library news, and even recruiting new team members. To these, we have added a paper.li webpage to collate library news everyday and a Google Maps API to show which libraries are under threat. Our online presence requires a great deal of commitment and effort from the team members maintaining the profiles—particularly on Facebook and Twitter which require updates 7 days a week—but it is necessary to keep the campaign strong and build on momentum.

Behind the scenes, we use a variety of tools to co-ordinate efforts: a PBworks wiki, Doodle, Chatzy, email. These allow us to hold team meetings, share materials sent to us by supporters, work together on promotional materials, and formulate effective strategies for developing the campaign. Our team communication through social media tools has been so effective that we’ve only had to meet face-to-face once so far.

WIth over 400 libraries now under threat, it's even more important for the team to react quickly and spread the word as far as possible. The power of social media for promotion was demonstrated on 16 January when library user, mardixon, asked Twitter users why libraries were important. Within a few hours and some supporting tweets from Voices for the Library, the #savelibraries hashtag got over 5000 tweets and became a trending topic first in the UK and then worldwide. Thousands of people heard about the threat to libraries that day, many of whom would never have heard about it via traditional media.

Social media has allowed us not only to set up a national campaign group that otherwise could not have existed but also to spread the word effectively and cheaply and to reach people we would otherwise not have reached – politicians, journalists, celebrities, and most importantly, library users. Voices for the Library will continue to use social media and experiment with new tools so that we can give voices to people who value the UK’s public library service.

Simon Barron is a librarian for the British Army and a campaigner with Voices for the Library. He recently completed a Masters in Library and Information Management and his special interests include the use of digital technologies in libraries, ebooks, and digital libraries. He tweets as @simonXIX

Love your librarian

Plans for volunteers to run libraries are not viable, as the technical knowledge and expertise of professional librarians is irreplaceable

Libraries are facing an unprecedented assault from local councils up and down the country, and the government appears unwilling to intervene despite library cuts that may be in breach of the Public Libraries and Museums Act. Some 400 libraries are threatened with closure over the course of this year, with services in Doncaster, Gloucestershire and the Isle of Wight amongst many threatened with devastating cuts. Many councils seem to believe that volunteer run libraries are an adequate solution to funding issues. In the age of the digital library this is a gross error.

But it’s not just internet searching which makes digital literacy a key skill, the increasing prevalence of digital materials presents a number of problems. Digitisation is becoming an important part of the modern public library service. Across the country libraries hold a range of materials that many people never get to see. Locked away in filing cabinets out of the reach of the general public, there are materials of local importance that both library users and non-users are completely oblivious to. Many public libraries have started digitising such materials to ensure that they can be shared on the Internet and therefore be viewed by people who would normally not have access to them. Tools such as Flickr are currently being used to share collections (such as Plymouth’s Barbican collection) as well as embedding collections on library websites (such as the National Library of Wales’ collection).

As JISC—the Joint Information Systems Committee—outlines, there are many considerations before embarking on a digitisation process. For example—just as with books—preservation of digital items is vital. Central to the issue of preservation are file formats which, as JISC highlights, can prove ‘overwhelming for someone new to the world of digital imaging’. Failure to save a digital image in an appropriate format, for example, can result in that image becoming inaccessible at a later date as new formats emerge or as new technologies develop. This would ultimately result in resources wasted as digital images are re-created at a later date or worse, the image is lost forever due to loss of the original. It is a costly error that can be avoided if trained staff are responsible for such a complex project rather than untrained volunteers.

But it is not just the creation of the digital image that is important; how the public access it is also crucial to the success of a digitisation project. Careful consideration needs to be given to where the image should be stored and how it can be accessed. As with file formats, understanding of the different tools can ensure the success or failure of a digitisation project. Using Flickr is a popular choice, but what happens when Yahoo! pulls the plug (as has been rumoured – though strenuously denied)? And if hosting on your own website, how do you ensure the digital images are accessible to as many people as possible? What techniques do you employ to ensure that library users can access the image quickly and easily?

There are also a number of other considerations that need to be taken into account when developing a digital library collection. Questions around copyright, for example, need to be resolved before any project can proceed for obvious reasons. Obtaining copyright clearance can be time consuming and costly as both Hampshire County Council and the University of Swansea discovered upon embarking on their respective digitisation programs. Again, these are complex (in this case legal) issues that volunteers are not best placed to deal with.

All of these considerations make it hard to see how volunteers are in a better position than trained professionals to take libraries into the 21st century. Aside from the issues outlined above, there is the issue of the prohibitive costs associated with online resources (such as Encyclopaedia Britannica), let alone organising content and troubleshooting. Truth is, even those that run volunteer (or ‘community’) libraries believe that they provide a second class service when compared to council run libraries staffed by trained staff and professionals. Councils across the country seem to believe that there is an unlimited supply of Wired reading, technologically savvy, digitally literate volunteers out there waiting to be given the opportunity to lead their library service into the digital age. For libraries to truly prosper, however, they need skilled, highly trained librarians who understand the issues that the digital world presents, and can ensure libraries are central to the digital revolution.

Ian Clark is currently completing an MSc in Information and Library Studies at Aberystwyth University and is a founder of Voices for the Library. He tweets as @ijclark.

Image: CC-AT-SA Flickr: gaelx

Everybody loves surfing

Threats of library closures have sparked protests all over, but it's more than just access to books which is at stake

A few months ago I was standing outside my local public library waiting for it to open. Within a few minutes a handful of people had joined me. When the doors opened we all filed in. Everyone else headed straight for the computers leaving me alone to browse the shelves. At first I was surprised by this—I never use the computers at the library—but then it occurred to me, I am one of the lucky ones who has a computer and access to the internet at home. This hasn’t always been the case though, and when I had no internet access at home where did I go to get online? The library of course.

According to a survey on Internet Access conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 27% of UK households do not have internet access. The same study links internet usage to a number of socio-economic factors; according to Mark Williams from the ONS, those less likely to have used the internet are typically less educated and from families on lower incomes. We might assume, therefore, that these groups are also likely to form a large proportion of the households without internet access. It is precisely these groups who benefit from the free access to the internet that public libraries provide.

Internet access is now being discussed as a basic human right. A growing number of European countries are setting this down in law and it is on the agenda of the UN’s International Telecommunications Union. Amongst other, more controversial proposals, the UK government’s Digital Economy Bill was promising to deliver broadband access throughout the UK by 2012. However, with one year to go, they are a long way off. If internet access for all is to be believed as a priority for the government, then surely closing public libraries and removing some people’s only access point to the internet is taking a step backwards?

Simply providing access to computers and the internet, however, isn’t enough; people need to be taught about the nature of online information, how to search for and evaluate information, and how to stay safe online. In the ONS survey on internet access, 21% of the people who said that they did not have internet access at home stated it was because of a lack of skills. This doesn’t surprise me; both through my work in a university library and conversations with friends and family, I am often shocked by people’s lack of awareness about what they do and can do online.

These are not just skills that adults need to have to be able to function online; our kids need them too. It is wrong to assume that those people who have grown up with the Internet know what they are doing online. I see so many students from the so-called Net Generation who appear to have no clue about how their actions online now may come back to haunt them in the future. Whilst there are moves to embed digital literacy into the school curriculum, there is also a need for parents to teach their kids about these issues too. In a conversation about social networking with colleagues at work recently, I heard about their concerns over how their children were using these sites. Issues related to the content they were sharing and how trusting they were of the people they were sharing personal information with, were of particular concern. Although parents may be aware of the issues surrounding their children’s use of the internet, do they know enough to be able to teach them how to use it responsibly?

The internet is a new world with a new set of rules, and it can be daunting. I—and many of my peers—have learnt about this world through experimentation, but many people will want some guidance from a source they trust. This is where public libraries can help. In addition to providing the equipment to get people online they can provide training in basic computing skills, online communication, information retrieval and online security. An example of this in action is in Newcastle’s libraries where a series of introductory IT training sessions are run. These cover topics such as ebooks, online shopping, email and social networking, and accessing health information online.

Public libraries have a role to play in so many more spheres than the provision of books; providing access to the Internet and learning opportunities are just two of them. The loss of public libraries is not only a loss of access to books, but also a loss of access to information of all kinds.

Emma is an academic librarian interested in the changing role of libraries in the digital age. She tweets as @ekcragg and blogs here.

Fogged

Amidst debates over privacy vs security, what can we learn from the model historically employed by gentlemen's clubs in the nineteenth century?

The Reform Club, I read on its website, was founded as a counterweight to the Carlton Club, where Conservatives liked to meet and plot away from public scrutiny. To most of us, it's the club where Phileas Fogg made and won his bet that he could travel around the world in 80 days – no small feat in 1872.

On Wednesday, the Club played host to a load of people who don't usually talk to each other much because they come at issues of privacy from such different angles. Cityforum, the event's organizer, pulled together representatives from many parts of civil society, government security, and corporate and government researchers.

The key question: what trade-offs are people willing to make between security and privacy? Or between security and civil liberties? Or is "trade-off" the right paradigm? It was good to hear multiple people saying that the "zero-sum" attitude is losing ground to "proportionate". That is, the debate is moving on from viewing privacy and civil liberties as things we must trade away if we want to be secure to weighing the size of the threat against the size of the intrusion. The disproportion, for example, of local councils' usage of the anti-terrorism aspects of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act to check whether householders are putting out their garbage for collection on the wrong day, is clear to all.

It was when the topic of the social value of privacy was raised that it occurred to me that probably the closest model to what people really want lay in the magnificent building all around us. The gentlemen's club offered a social network restricted to "the right kind of people" – that is, people enough like you that they would welcome your fellow membership and treat you as you would wish to be treated. Within the confines of the club, a member like Fogg—who spent all day every day there—would have had, I imagine, little privacy from the other members or club staff, whose job it was to know what his favourite drink was and where and when he liked it served. But the club afforded members considerable protection from the outside world. Pause to imagine what Facebook would be like if the interface required each would-be addition to your friends list to be proposed and seconded and incomers could be black-balled by the people already on your list.

This sort of web of trust is the structure the cryptography software PGP relies on for authentication: when you generated your public key, you were supposed to have it signed by as many people as you could. Whenever someone wanted to verify the key, they could look at the list of who had signed it for someone they themselves knew and could trust. The big question with such a structure is how you make managing it scale to a large population. Things are a lot easier when it's just a small, relatively homogeneous group you have to deal with. And, I suppose, when you have staff to support the entire enterprise.

We talk a lot about the risks of posting too much information to things like Facebook, but that may not be its biggest issue. Just as traffic data can be more revealing than the content of messages, complex social linkages make it impossible to anonymise databases: who your friends are may be more revealing than your interactions with them. As governments and corporations talk more and more about making "anonymised" data available for research use, this will be an increasingly large issue. An example is a little-known incident in 2005, when the database of a month's worth of UK telephone calls was exported to the US with individuals' phone numbers hashed to "anonymise" them. An interesting technological fix comes from Microsoft with the notion of differential privacy – a system for protecting databases both against current re-identification and attacks with external data in the future. The catch, if it is one, is that you must assign to your database a sort of query budget in advance – and when it's used up, you must burn the database because it can no longer be protected.

Public opinion polls are a crude tool for measuring what privacy intrusions people will actually put up with in their daily lives. A study by Rand Europe released late last year attempted to examine such things by framing them in economic terms. The good news is they found that you'd have to pay people £19 to get them to agree to provide a DNA sample to include in their passport. The weird news is that people would pay £7 to include their fingerprints. You have to ask: what pitch could Rand possibly have made that would make this seem worth even one penny to anyone? By contrast, we also know the price people are willing to pay for club membership.

Hm. Fingerprints in my passport or a walk across a beautiful, mosaic floor to a fine meal in a room with Corinthian columns, 25-foot walls of books, and a staff member who politely fails to notice that I have not quite conformed to the dress code? I know which is worth paying for if you can afford it.

Wendy M. Grossman’s website has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Image: CC-AT-SA Flickr: pit-yacker

Tweeting for justice

A judge's decision to allow journalists to tweet from the courtroom promotes the values of liberal democracy and justice, says Laura MacPhee

WikiLeaks has been described as “holding a mirror to journalism” – some journalists have been threatened by this rival, fearing that by exposing secrets, WikiLeaks undermines the value of investigative journalism. But journalists have a lot to thank Julian Assange for; not only does his innovative work and colourful personal life provide a wealth of material for them, but the developing legal case against him is a continuing source of interest to the public.

Moreover, WikiLeaks has spawned an interest in developing new and creative ways for technology to aid journalism. A significant development is that journalists are now permitted to use Twitter to provide live coverage from the courtroom.

This has been quite roundly met with jubilation. Speed is a valuable commodity when it comes to news reporting – to remain competitive you must be able to produce a story before your opposition. Twitter facilitates this by allowing instantaneous reporting. This is particularly advantageous in an era where print media has all but been surpassed by online journalism. Digital newspapers can offer live coverage of events, as happened during the rescue of the Chilean miners. Tweeting from court will extend the range of stories which can be broadcast contemporaneously.

Twitter can be used to promote the values of liberal democracy. Indeed, press freedom is vital to pursuing such ends – allowing journalists to tweet judicial proceedings lends them greater transparency. The public can access information about the case as it progresses, which exposes the case to public scrutiny, and tends to encourage procedural propriety.

Open justice is a core feature of the British constitution, and simultaneous reporting can be used to further this.

Twitter’s CEO, Dick Costolo, stated that Twitter was designed to “connect people for a purpose” – features such as hashtags allow users easy access to a vast amount of information on any given topic; people can reach a wide—but targeted—audience, particularly with the benefit of retweeting; and users can contact a group who are likely to be interested in what they have to say. It’s no surprise, then, that Twitter has become a popular tool for online marketing, as well as news reporting.

Inevitably, the introduction of Twitter into judicial reporting has also attracted its critics, but, given proper administrative guidelines, their fears seem largely unfounded. The usual safeguards would apply to reporting via Twitter. There may be matters discussed in court which cannot be reported, especially where the information could threaten national security. Such cases would continue to be conducted privately, away from the gaze of the press. Journalists would not ordinarily be permitted to print such information, so the risk is made no greater by the introduction of Twitter.

Certain quarters have expressed concerns about the distraction caused by electronic devices. The judge who allowed the use of Twitter has sought to limit this risk by restricting its use to only journalists – other members of the public do not enjoy the same freedom. Whilst this may be slightly problematic in implementation, is seems reasonable and should allay anxieties about distraction.

Owing to the exigency of the question at hand, Lord Justice Judge could offer only interim guidance. His edict took effect immediately, pending a full review of the issue. The reception, however, has been so positive that it seems likely that this review will confirm his decision.

Laura MacPhee is recent graduate of Oxford University, where she read Jurisprudence. She researches copyright related issues for the Open Rights Group.

A misguided approach

EU measures to block access to websites which host indecent child images threatens both our freedom and privacy, and is not the most effective way to combat child abuse

A new directive tocombat child exploitation is reaching the final stages in the European Parliament. The draft measures contain controversial powers to block access to websites believed to host child abuse material, but would impose a censorship infrastructure on the Internet.

Child abuse crimes are undoubtedly a serious issue but the use of overtly emotional language can be dangerous and misleading. The tone adopted by some supporters of the proposals risks distorting the debate, and it leaves those who oppose the plans in the tricky position of being portrayed as arguing against defending children.

But there is much evidence to suggest that blocking is not an effective way to prevent child abuse, and that these proposals are ultimately harmful. The German organisation MOGiS (MissbrauchsOpfer Gegen InternetSperren, or Abuse Survivors Against Internet Blocking), who have been campaigning since 2009, assert: “We are opposing the blocking of web pages as a means to tackle the circulation of the images of sexual child abuse on the internet”. Founder of the group, Christian Bahls, speaks and writes powerfully about his deep concern for these plans to “block access to websites using a secret blocking list that is being exchanged by police forces without any involvement of the justice system”.

Also campaigning against the measures is EDRi, an international non-profit association which promotes digital rights. EDRi have published a booklet titled Internet blocking: Crimes should be punished and not hidden, which is full of detailed analysis. As Joe McNamee, an expert with EDRi, explained in a meeting at the European Parliament and in an article for Index on Censorship, web blocking is “useless” and means that “citizens are led to believe that something is being done, and politicians can take refuge in a populist policy in the full knowledge that blocking has no positive benefits and leaves the websites online”.

A similar argument was put forward by EuroISPA (who represent over 1800 ISPs) who emphasised that “blocking allows images to remain online and available for use by those who present a real danger to children. These criminals make it their business to know how to circumvent blocks and continue to copy and share images”.

Opponents argue that the proposed measures are flawed: they fail to adequately address the actual issue of child abuse; implementation across countries with vastly differing laws is technically implausible; there is a lack of judicial control; and they pose a distinct threat to fundamental rights, most notably freedom of expression and the right to privacy (more on these rights-based issues in an open email to MEPs).

Worryingly, these measures have already passed through preliminary stages. Last week, the Committee on Civil Liberties (LIBE) held a hearing to discuss the plans in more detail, and members now have a brief chance to table amendments with a vote scheduled for 3 February. After this, the directive will advance to the final stage, when all MEPs have the opportunity to vote on it.

Whilst we debate Article 21 of the proposed directive that is set to sanction the censoring powers, it is important to remember that other Article 21 (of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), which upholds that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government”: herein lies our right to protest against flawed, ineffective and potentially dangerous measures.

Amalia is an independent writer who supports human rights including internet freedom. She writes at amaliaking.co.uk and tweets as @amaliakinguk

*This article was modified on 20 January 2011

Face time

Goldman Sachs' enormous valuation of Facebook implies that this social network is in for the long haul, but previous online networking trends suggest otherwise

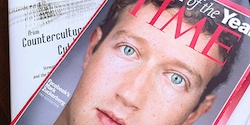

The history of the net has featured many absurd moments, but this week was some sort of peak of the art. In the same week I read that a) based on a $450 million round of investment from Goldman Sachs, Facebook is now valued at $50 billion – higher than Boeing's market capitalization and b) Facebook's founder, Mark Zuckerberg, is so tired of the stress of running the service that he plans to shut it down on 15 March. As I seem to recall a CS Lewis character remarking irritably, "Why don't they teach logic in these schools?" If you have a company worth $50 billion and you don't much like running it any more, you sell the damn thing and retire. It's not like Zuckerberg even needs to wait to be Time's Man of the Year.

While it's safe to say that Facebook isn't going anywhere soon, it's less clear what its long-term future might be, and the users who panicked at the thought of the service's disappearance would do well to plan ahead; if there's one thing we know about the history of the net's social media, it's that the party keeps moving. Facebook's half-a-billion-strong user base is, to be sure, bigger than anything else assembled in the history of the net. But I think the future as seen by Douglas Rushkoff, writing for CNN last week is more likely: Facebook, he argued based on its arguably inflated valuation, is at the beginning of its end, as MySpace was when Rupert Murdoch bought it in 2005 for $580 million. (Though this says as much about Murdoch's net track record as it does about MySpace: Murdoch bought the text-based Delphi, at its peak in late 1993.)

Back in 1999, at the height of the dot-com boom, the New Yorker published an article (abstract; full text requires subscription) comparing the then-spiking stock price of AOL with that of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) back in the 1920s, when radio was the hot, new democratic medium. RCA was selling radios that gave people unprecedented access to news and entertainment (including stock quotes); AOL was selling online accounts that gave people unprecedented access to news, entertainment, and their friends. The comparison, as the article noted, wasn't perfect, but the comparison chart the article was written around was, as the author put it, "jolly". It still looks jolly now, recreated some months later for this analysis of the comparison.

There is more to every company than just its stock price, and there is more to AOL than its subscriber numbers. But the interesting chart to study – if I had the ability to create such a chart – would be the successive waves of rising, peaking, and falling numbers of subscribers of the various forms of social media. In more or less chronological order: bulletin boards, Usenet, Prodigy, Genie, Delphi, CompuServe, AOL, and now MySpace, which this week announced extensive job cuts.

At its peak, AOL had 30 million; at the end of September 2010 it had 4.1 million in the US. As subscriber revenues continue to shrink, the company is changing its emphasis to producing content that will draw in readers from all over the Web – that is, it's increasingly dependent on advertising, like many companies. But the broader point is that at its peak, a lot of people couldn't conceive that it would shrink to this extent, because of the basic principle of human congregation: people go where their friends are. When friends gradually start to migrate to better interfaces, more convenient services, or simply sites their more annoying acquaintances haven't discovered yet, others follow. That doesn't necessarily mean death for the service they're leaving: AOL, like CIX, the The WELL, and LiveJournal before it, may well find a stable size at which it remains sufficiently profitable to stay alive, perhaps even comfortably so. But it does mean it stops being the growth story of the day.

As several financial commentators have pointed out, the Goldman investment is good for Goldman no matter what happens to Facebook, and may not be ring-fenced enough to keep Facebook private. My guess is that even if Facebook has reached its peak it will be a long, slow ride down the mountain and between then and now. at least the early investors will make a lot of money.

But in the long term, we should remember that Facebook is barely five years old. According to figures leaked by one of the private investors, its price-earnings ratio is 141. The good news is that if you're rich enough to buy shares in it you can probably afford to lose the money.

As far as I'm aware, little research has been done on the net's migration patterns. From my own experience, I can say that my friends lists on today's social media include many people I've known on other services (and not necessarily in real life) as the old groups reform in a new setting. Facebook may believe that because the profiles on its service are so complex, including everything from status updates and comments to photographs and games, users will stay locked in. Maybe. But my guess is that the next online party location will look very different. If email is for old people, it won't be long before Facebook is too.

A hacker's playground

Fail0verflow's successful hacking of Sony's Playstation 3, prompts us to question the legitimacy of DRM and who really owns the the hardware we buy

Four t-shirted figures stand behind a brightly lit desk at the front of a stage. Reigning above is a large screen displaying a simple black and green slide-show presentation, illuminating an otherwise dark hall. Some would call them hackers, others perhaps pirates. But one thing we can all agree on is this: they are nerds.

Team Fail0verflow appeared at the 27th Chaos Communications Congress in December 2010 to tell the world about the so-called “PS3 Epic Fail”. They were the ones responsible for hacking the encryption that Sony’s PlayStation 3 gaming console uses to authenticate approved media and software.

The Fail0verflow group, formerly Team Twiizers, originally gained fame for breaking the Nintendo Wii's security systems in order to run a customised channel on the device allowing for third party code. The channel is said to run on just over 1% of all Nintendo Wiis – that's pretty good going.

A bunch of nerds hacking their way around consoles in order to run Linux on it may seem pretty pointless to the less technically inclined. Indeed, there's only so many jokes one can make about installing Linux on wristwatches and lemons before the practical side must be revealed; however, you're ORG readers so the usefulness of this ought to hit you with the subtlety of a hot brick. One word: freedom. Many a Digital Rights Management (DRM) system has come and fallen beneath the mighty keyboard of free software advocates. It's hard to overstate how important free software is to the academic community at large – the ability to share code, and in turn ideas, is one of the pillars of the information age. But what about hardware?

The joy of personal computers is the ability to run one's own software. With my PC, a text editor and a compiler I can make my PC do almost anything I want. DRM has recently become a larger threat to the PC hobbyist: sneaky processes running in the background; monitoring what the user does; checking and verifying. With hardware, these types of rights infringement are often much harder to get around because they're fundamental to the design of the system. But the hardware inside the PS3 is advanced, and almost certainly faster than most people's desktop PC; it's understandable why users may want access to it – to be able to harness this power for one's own code is quite an impressive feat.

It seems as if Sony's managed to score an own goal by limiting the software running on the console; the removal of OtherOS functionality irked users, who then began hacking the system. Sony's initial embrace of hardware hobbyists meant that this change of tack was effectively like luring them in only to slap them round the head with a large trout. One of the guests on the panel at the conference in December stated, “Linux is inevitable. Either you support Linux on your hardware or it will be hacked so it will run sooner or later.” Indeed, Linux/GNU operating systems have become symbols of software freedom and certainly an inspiration to amateur hackers.

Sony, for their part, are worried about piracy; users, on the other hand, are concerned about cheating during online games. Sony are insistent that these flaws can be fixed, but hobbyists are not convinced that a simple software patch will be able to fix the “security holes” . What's more is that these openings could potentially give way for third party games on the PS3 – though Sony will certainly put up a fight.

Despite the fact that Sony are still enjoying a healthy market share from console and game sales, their executives are nonetheless uneasy about the hack, and are proceeding with their attempt to sue Fail0verflow. That said, legal action is unlikely to deter those who are persistent at gaining access to the hardware; hobbyists hack for fun and additional patches in this case simply present more challenges to pique the intrigue of hackers everywhere. Ultimately, DRM becomes nothing more than a playground for ever-delighted hackers.

Graham Armstrong is a computing student with a strong interest in free software, and the use of social media technology to aid transparency and democracy. He tweets as @LupusSLE.

Image: Graham Armstrong

It’s not a bug, it’s a feature

Frustrated Windows users from the 1990s are all too familiar with the implications of “It’s not a bug, it’s a feature” – a phrase that excuses limitations of software. Now proponents of DRM seem to be rehashing the same old excuse

Amazon’s Kindle has been the 2010 Christmas rage, but the DRM limitations on the product are endlessly infuriating. The adverts trying to tell me that I can read my Kindle books on any device are incredibly misleading: you can read your ebooks on your desktop and your laptop and your Kindle and your iPhone and your Android phone, because there’s a Kindle app for all of them. But what, dear Amazon, happens if I want a Sony e-reader, or if my laptop happens to run on Linux? In effect, tough beans.

What’s worrying is that this seems to be a deliberate strategy in the content industry, and the trend is catching on. Ultraviolet is an initiative from the major Hollywood studios and music labels (only Apple and Disney aren’t on board) with the helpful tagline “Freedom of Entertainment”. It claims to allow you to use any of your Ultraviolet-enabled content on any of your devices. So you buy a movie once, in any Ultraviolet-enabled format—this could be a DVD or BlueRay disc, or it could be a download—and you can view it on your PC, your laptop, your smartphone, or your old-fashioned television. That is, as long as all of your devices are Ultraviolet-enabled too.

Details of exactly how it will work and what devices will be Ultraviolet-enabled are still fairly unknown. It looks like an internet connection will be required, so unless you buy the DVD/BlueRay, you will not have a local copy of your content - and here you were thinking you could just spend that 10-hour flight catching up on Desperate Housewives. It also looks like you will be able to register up to six other users on your household account, which makes a nice change from having to buy separate copies of your content for you and your significant other. And it looks like the DRM will (try to) stop you from viewing your content on non-Ultraviolet devices.

One issue of some concern is that of privacy: building a cloud-based digital content library means that the amount of data the companies behind Ultraviolet will have on you (what you watch, when you watch it, what device you watch it on) is quite considerable. Even if they manage to refrain from using it for targeted advertising, I would be very surprised if they didn’t find another way to monetise it. There are also privacy issues between different household members; I suspect parents will be able to have a locked part of the account to restrict access to content they deem inappropriate for their children, but what about other users on the same account?

But more concerning is the issue of being sold DRM as a "feature". If something claims to “free my entertainment” and enable consumer choice, then that’s what it should be expected to do. It should not tie me to a particular set of devices – if you thought you’d be able to play your DVDs on your iPad, think again, because Apple’s chosen to opt out of Ultraviolet. Nor should it tie me to a particular operating system – the lengths a Linux user must go to in order to load music onto an iPod are simply inconceivable, and I suspect the Linux coverage of Ultraviolet will also be non-existent. Furthermore, I should not have to sign lengthy licensing agreements which tell me what I can and can’t do with something I have purchased. There’s a good reason why I still buy CDs rather than downloading from Amazon or iTunes, and I suspect Ultraviolet will have similar legalese attached to it. All of these things tie me up and limit my choices, which is the exact opposite of what Ultraviolet claims to do.

In principle, Ultraviolet does try to meet a genuine consumer need. It suggests that the industry is finally grasping the idea that consumers do not appreciate having to buy the same product again and again just because technology changes. It's also attempting to cater to the demand for the greater flexibility of being able to view content wherever and on whichever device happens to be at hand. But whilst the idea is sound in principle, the implementation leaves a lot to be desired – Ultraviolet are effectively selling something which limits choice (a bug) under the pretence of something that enables choice (a feature).

If the industry really wants to free entertainment and enable consumer choice, they should perhaps listen to someone like Free Software activist Richard Stallman, who proposed two methods for funding art and content creation – taxation or voluntary donation. Interestingly, both of these suggestions are implicitly based on the assumption that content is a public good; unfortunately for the entertainment industry, the profit margins on public goods aren’t anything like what they’re used to.

Dodgy salesmen?

Do you think you're "buying" an ebook? If so, you may want to think again

Amazon’s Kindle product page quotes professional reviewers as saying: “allowing you to click, buy, and start reading your purchases in 60 seconds”; "the next time you hear about a great book, just search, buy, and read”; “simply buy and download the whole book with 1-Click”.

It’s pretty clear, right? Amazon sells you ebooks. Simple!

Or does it?

“Use of Digital Content.

Upon your download of Digital Content and payment of any applicable fees (including applicable taxes), the Content Provider grants you a non-exclusive right to view, use, and display such Digital Content an unlimited number of times, solely on the Kindle or a Reading Application or as otherwise permitted as part of the Service, solely on the number of Kindles or Other Devices specified in the Kindle Store, and solely for your personal, non-commercial use. Unless otherwise specified, Digital Content is licensed, not sold, to you by the Content Provider.

“Neither the sale or transfer of the Kindle to you, nor the license of the Software or Digital Content to you, transfers to you title to or ownership of any intellectual property rights of Amazon or its suppliers or the other Content Providers. All licenses are non-exclusive and all rights not expressly granted in this Agreement are reserved to Amazon or the other Content Providers.”1

Think again! You’re not actually buying something. You’re licensing the use of an ebook. You can’t buy a licence. You pay a fee, they share some of their rights with you. This is a massive, massive difference between the physical books sold today, and ebooks. An ebook is not your property, it remains, at all times, Amazon’s property. You enter into a long-lasting contract with them, which is how, even after you’d thought the transaction was over, they can still require that, until the end of your life, you obey their terms, such as:

“Limitations. Unless specifically indicated otherwise, you may not sell, rent, lease, distribute, broadcast, sublicense, or otherwise assign any rights to the Digital Content or any portion of it to any third party, and you may not remove or modify any proprietary notices or labels on the Digital Content. In addition, you may not bypass, modify, defeat, or circumvent security features that protect the Digital Content.”1

Break any conditions of the agreement, and they will take back what you thought you’d bought. Or they could sue you for breach of contract. Or maybe even copyright infringement, which if you’re in the US, is particularly scary since (as we all know) they have statutory damages there: no need for Amazon to prove it actually suffered harm; they can claim arbitrary amounts from you anyhow.

In fact, they could deprive you of the ‘book’ which they told you that you were ‘purchasing’ even if you held up your end of the bargain perfectly. They already have, several times. They reserve the right to take what you paid for back if they want:

“Changes to Service. We may modify, suspend, or discontinue the Service, in whole or in part, at any time.”1

Got a problem with that, UK user of Amazon.co.uk? Take it to the courts of Luxembourg City, Dorothy!

“Disputes. Any dispute arising out of or relating in any way to this Agreement will be adjudicated in the courts of the judicial district of Luxembourg City, and you consent to non-exclusive jurisdiction and venue in such courts.”1

You may find yourself saying, "Waaah? But they said I was buying an ebook! It's all over the product page and checkout process! I thought that the repeated insistence on purchasing and buying meant that I was exchanging my money for something that becomes my property, not paying for a stinking licence!"

Well, tough luck.

“Complete Agreement and Severability. This is the entire agreement between us and you regarding the Kindle, Digital Content, Software, and Service and supersedes all prior understandings regarding such subject matter.”1

And you know what? If Amazon wants to make it a term of your ebook licence that you wear a party hat whilst reading it upside down, or make you pay again, and say thank you sir, then it can:

“Amendment. We may amend any of the terms of this Agreement in our sole discretion by posting the revised terms on the Kindle Store or the Amazon.co.uk website.”1

And remember, kids:

“Kindle is our #1 bestselling item for two years running. It's also the most-wished-for, most-gifted, and has the most 5-star reviews of any product on Amazon.com."2

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.