Brighton Mini Maker Faire

Natalia Buckley, one of the organisers of the Brighton Mini Maker Faire, celebrates and reviews the creative event, explaining what it is all about.

On the 8th of September Brighton became the centre of the maker universe, or at least the maker universe in the south east of England. Brighton Mini Maker Faire has opened doors for the second time showcasing things made by over 70 makers. By makers I mean everyone from electronics enthusiasts, through crafters, artists, woodworkers, science hobbyists, to engineers and computer programmers.

Maker Faire is a celebration of all things DIY: ranging from arts and crafts to robots and engineering. The first event of its kind was organised by Make magazine and was held in San Mateo, CA, but the idea quickly spread, and soon, alongside the official Maker Faires, a number of community organised events began appearing. These unofficial ones are called Mini Maker Faires, much like community organised events under the TED spirit are called TEDx - though often they are Mini only in the name.

The Brighton event is run by a small army of dedicated volunteers, many of whom are members of the local hackspace, BuildBrighton. This interactive festival of creativity and invention only lasts one day, but is jam packed full of activities and exhibits that the whole family can enjoy.

This year over 70 makers had the opportunity to show their creations and inventions, including a long table full of 3D printers and many Raspberry Pi hacks.

One of my favourites were Makies, 3D printed personalised action dolls, which can later be modded in many ways.

A map of the original Laines, Furlongs and Paul strips of old Brighton was being knitted throughout the day - all made out of locally sourced, carded, spun and dyed wool.

Noisy Table was also great fun. It's an interactive table tennis instrument hybrid - as you play, different sounds are triggered depending on where the ball hits the table. It came to life a result of a collaboration between the artist Will Nash and a local maker, Jason Hotchkiss, who worked on engineering the electronics.

Artefact cafe, who are a group of design researchers from Brunel University, were collecting data about the maker community to inform their research about maker and hacker spaces. It will be very interesting to see how this project progresses, hopefully with some interesting input from visitors and exhibiting makers alike.

Apart from the opportunity to look at some incredible projects, talk about them with their creators and learn how they were made, there were a number of workshops people of all ages were invited to attend. There was a soldering workshop, where you could learn some simple electronics too. Throughout the day is was full of kids and adults, in equal measure boys and girls, becoming excited about making their own badges with a flashing LED.

The was also a chance to build a chair that could support your weight out of cardboard, using no glue or tape, or your own air balloon with Science Museum. Teachers from Dorothy Stringer and Cavendish School as well as University of Kent were introducing visitors to coding using the Greenfoot system - an interactive programming environment especially suited to graphical applications and games. You could make your own speakers at a workshop run by Technology Will Save Us, who also helped a number of people to build a sensor that would remind you to water your dry plants. For crafters the highlight surely must have been making creations out of willow with Maia Eden. Many of the exhibiting makers have also run drop-in workshops at their stands, where you could learn about their process and try it out at the same time, so there was no shortage of things you could do with your hands.

We've also hosted talks by makers of all kinds about their creative process. Tom Armitage spoke about making things you don't know how to make yet. Alice Taylor talked us though the process of discovering how to make toys. Matt Webb demoed the Little Printer and told us about the challenges of industrial production once you decide to bring your creations to a wider audience. Leila Johnston inspired us to make things fast and to not be too precious about projects; just finish them and get on to the next ones.

Linda Sandvik from Code Club recalled how the initiative came about. Donna Comerford and her students from Cavendish School told us about the games the students have made, how they've developed a game-making process and how they went about testing them. Afterwards we had a short discussion chaired by Matt Locke about teaching to value work made by hands, thinking through making, and preparing the next generation to be unafraid of trying things out and making stuff.

I see the maker movement as complimentary to the Open Data and Open Source movements. Many makers talk about their prototyping process, publish their source files, talk through replicating their inventions and share the knowledge they have accrued so that others can also benefit from it. There are many reasons makers exhibit at the Faire, but sharing what they know, and sharing the excitement that comes from making things often come up. Many creations wouldn't be possible without the openness and generosity of others: without the open source tools and libraries we wouldn't have the Arduino (electronics prototyping platform), Raspberry Pi (tiny $25 computer) or the RepRaps (self-replicating 3D printer).

If you've missed the Brighton Mini Maker Faire, there are many others you could visit worldwide, with the Norfolk one coming up on 20th October.

Image: Images by Natalia Buckley, used with permission

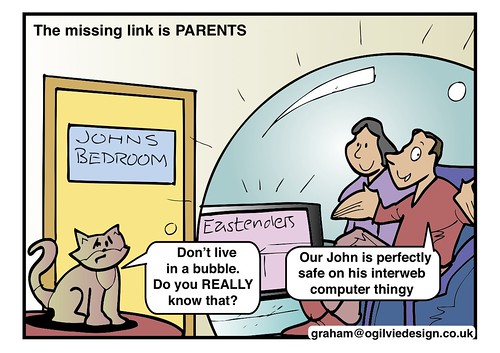

What did you learn in school today?

Wendy Grossman introduces a series of education themed articles on ORGzine with a look at the lessons kids are learning from the amount of personal data monitored in schools – finger printing to check library books out, cameras in toilets and tracking chips originally intended for livestock registering attendance.

One of the more astonishing bits of news this week came from Big Brother Watch: 207 schools across Britain have placed 825 CCTV cameras in toilets or changing rooms. The survey included more than 2,000 schools, so what this is basically saying is that a tenth of the schools surveyed apparently saw nothing wrong in spying on its pupils in these most intimate situations. Overall, the survey found that English, Welsh, and Scottish secondary schools and academies have a total of 106,710 cameras overall, or an average camera-to-pupil ratio of 1:38. As a computer scientist would say, this is non-trivial.

Some added background: the mid 2000s saw the growth of fingerprinting systems for managing payments in school cafeterias, checking library books in and out, and registering attendance. In 2008, the Leave Them Kids Alone campaign, set up by a concerned parent, estimated that more than 2 million UK kids had been fingerprinted, often without the consent of their parents. The Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 finally requires schools and colleges to get parental consent before collecting children's biometrics. That doesn't stop the practice but at least it establishes that these are serious decisions whose consequences need to be considered.

Meanwhile, Ruth Coustick, the editor of the Open Rights Group's ORGzine, sends the story that a Texas school district is requiring pupils to carry RFID-enabled (Radio Frequency Identification Device) chips cards at all times while on school grounds. The really interesting element is that the real goal here is primarily and unashamedly financial, imposed on the school by its district: the school gets paid per pupil per day, and if a student isn't in homeroom when the teacher takes attendance, that's a little less money to finance the school in doing its job. The RFID cards enable the school to count the pupils who are present somewhere on the grounds but not in their seats, as if they were laptops in danger of being stolen. In the Wired write-up linked above, the school's principal seems not to see any privacy issues connecting to the fact that the school can track kids anywhere on the campus. It's good for safety. And so on.

There is constant debate about what kids should be taught in schools with respect to computers. In these discussions, the focus tends to be on what kids should be directly taught. When I covered Young Rewired State in 2011, one of the things we asked the teams I followed was about the state of computer education in their schools. Their answers: dire. Schools, apparently under the impression that their job was to train the office workforce of the previous decade, were teaching kids how to use word processors, but nothing or very little about how computers work, how to program, or how to build things.

There are signs that this particular problem is beginning to be rectified. Things like the Raspberry Pi and the Arduino, coupled with open source software, are beginning provide ways to recapture teaching in this area, essential if we are to have a next generation of computer scientists. This is all welcome stuff: teaching kids about computers by supplying them with fundamentally closed devices like iPads and Kindles is the equivalent of teaching kids sports by wheeling in a TV and playing a videotape of last Monday's US Open final between Andy Murray and Novak Djokovic.

But here's the most telling quote from that Wired article: "The kids are used to being monitored."

Yes, they are. And when they are adults, they will also be used to being monitored. I'm not quite paranoid enough to suggest that there's a large conspiracy to "soften up" the next generation (as Terri Dowty used to put it when she was running Action for the Rights of Children), but you can have the effect whether or not you have the intent. All these trends are happening in multiple locations: in the UK, for example, there were experiments in 2007 with school uniforms with embedded RFID (that wouldn't work in the US, where school uniforms are a rarity); in the trial, these not only tracked students' movements but pulled up data on academic performance.

These are the lessons we are teaching these kids indirectly. We tell them that putting naked photos on Facebook is a dumb idea and may come back to bite them in the future - but simultaneously we pretend to them that their electronic school records, down to the last, tiniest infraction, pose no similar risk. We tell them that plagiarism is bad and try to teach them about copyright and copying - but real life is meanwhile teaching them that a lot of news is scraped almost directly from press releases and that cheating goes on everywhere from financial markets and sports to scientific research. And although we try to tell them that security is important, we teach them by implication that it's OK to use sensitive personal data such as fingerprints and other biometrics for relatively trivial purposes, even knowing that these data's next outing may be to protect their bank accounts and validate their passports.

We should remember: what we do to them now they will do to us when we are old and feeble, and they're the ones in charge.

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series

Image: CC-BY-SA Flickr: chadmiller

RoboCops

Last Sunday Neil Gaiman’s Hugo acceptance speech was silenced by copyright bots. Wendy Grossman explains why and how it happened and how the blunt robots are key context to the European consultation on the notice-and-takedown rules that govern, among other things, how ISPs are supposed to respond when copyright infriging material is uploaded.

Great, anguished howls were heard on Twitter last Sunday when Ustream silenced Neil Gaiman's acceptance speech at the Hugo awards, presented at the World Science Fiction Convention. On Tuesday, something similar happened when, Slate explains, YouTube blocked access to Michelle Obama's speech at the Democratic National Convention once the live broadcast had concluded. Yes, both one of our premier fantasy writers and the First Lady of the United States were silenced by over-eager, petty functionaries. Only, because said petty functionaries were automated copyright robots, there was no immediately available way for the organizers to point out that the content identified as copyrighted had been cleared for use.

TV can be smug here: this didn't happen when broadcasters were in charge. And no, it didn't: because a large broadcaster clears the rights and assumes the risks itself. By opening up broadcasting to the unwashed millions, intermediaries like Google (YouTube) and UStream have to find a way to lay off the risk of copyright infringement. They cannot trust their users. And they cannot clear - or check - the rights manually for millions of uploads. Even rights holder organizations like the RIAA, MPAA, and FACT, who are the ones making most of the fuss, can't afford to do that. Frustration breeds market opportunity, and so we have automated software that crawls around looking for material it can identify as belonging to someone who would object. And then it spits out a complaint and down goes the material.

In this case, both the DNC and the Hugo Awards had permission to use the bit of copyrighted material the bots identified. But the bot did not know this; that's above its pay grade.

This is all happening at a key moment in Europe: early next week, the public consultation closes on the notice-and-takedown rules that govern, among other things, what ISPs and other hosts are supposed to do when users upload material that infringes copyright. There's a questionnaire for submitting your opinions; you have until Tuesday, September 11.

Today's notice and takedown rules date to about the mid-1990s and two particular cases. One, largely but not wholly played out in the US, was the several-years fight between the Church of Scientology and a group of activists who believed that the public interest was served by publishing as widely as possible the documents Scientology preserves from the view of all but its highest-level adherents, which I chronicled for Wired in 1995. This case - and other early cases of claimed copyright infringement - let to the passage in 1998 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which is the law governing the way today's notice-and-takedown procedures operate in the US and therefore, since many of the Internet's biggest user-generated content sites are American, worldwide.

The other important case was the 1997 British case of Laurence Godfrey, who sued Demon Internet for libel over a series of Internet postings, spoofed to appear as though they came from him, which the service failed to take down despite his requests. At the time, a fair percentage of Internet users believed - or at least argued - that libel law did not apply online; Godfrey, through the Demon case and others, set out to prove them wrong, and succeeded. The Demon case was eventually settled in 2000, and set the precedent that ISPs could be sued for libel if they failed to have procedures in place for dealing with complaints like these. Result: everyone now has procedures and routinely operates notice-and-takedown, just as cyber rights lawyer Yaman Akdeniz predicted in 1999.

A different set of notice-and-takedown regime is operated, of course, by the Internet Watch Foundation, which was founded in 1996 and recommends that ISPs remove material that IWF have staff have examined and believe is potentially illegal. This isn't what we're talking about here: the IWF responds to complaints from the public and at all stages humans are involved in making the decisions.

Granted that it's not unreasonable that there should be some mechanism to enable people to complain about material that infringes their copyrights or is libellous, what doesn't get sufficient attention is that there should also be a means of redress for those who are unjustly accused. Even without this week's incidents we have enough evidence - thanks to the detailed collection of details showing how DMCA notices have been used and abused in the years since the law's passage being continuously complied at Chilling Effects - to be able to see the damage that overbroad, knee-jerk deletion can do.

It's clear that balance needs to be restored. Users should be notified promptly when the content they have posted is removed; there should be a fast turnaround means of redress; and there clearly needs to be a mechanism by which users can say, "This content has been cleared for use".

By those standards, Ustream has actually behaved remarkably well. It has apologized and is planning to rebroadcast the Hugo Awards on Sunday, September 9. Meanwhile, it's pulled its automated copyright policing system to understand what went wrong. To be fair, the company that supplies the automated copyright policing software, Vobile, argues that its software wasn't at fault: it merely reports what it finds. It's up to the commissioning company to decide how to act on those reports. Like we said: above the bot's pay grade.

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Internet blocking will still not protect our children

Representing the target demographic for the Department of Education consultation on default online blocking of adult content, Ryan Cartwright is a Christian, a parent and an IT professional – and he has five reasons why network level blocking is a terrible and ineffective idea.

The government is holding a consultation for a proposed new law which it says will protect children using the internet. This proposal follows a campaign which I first came across in February 2012. It is called “SafetyNet” and is being run by Premier Christian Media and SaferMedia. The campaign, and now the consultation is about requiring Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to “[block] pornography and other content at network level whilst giving adults a choice to ‘opt-in’ to this content”.

The consultation is fairly loaded and appears based upon the “facts” purported by the campaign. As far as I am concerned facts are facts. If a USA survey says “1 in 3 10 year olds have accessed pornography online”, I’m not going to argue.

I’m not altogether sure why 73% of UK households having internet access adds to the problem but I don’t doubt the figure is correct. What concerns me are the conclusions drawn and the way they are presented in the consultation document.

Perhaps I should introduce why I feel I can write about this. I am a UK Christian parent (so therefore fit neatly in the target demographic for the campaign), my children are between 5 and 9 years old and thus are well within the group the proposed law seeks to “protect”. I am also someone who works with and understands the “network level” Internet this consultation talks about.

I have been building and hosting webservers and websites since the mid 1990s and I still do. So I am fairly and squarely in the target demographic for the campaign, consultation and the proposed law. I would add I am also one of the people who understands the technology involved and by the sound of it I understand it better than those running the campaign or making the proposal.

A parent will always be the best protection for a child on the Internet. Image CC:By-NC-SA OllieBray

Why this won’t work

The campaign calls for ISPs to “block pornography” at “network level”; the consultation expands this into two options. Firstly a universal switch which enables or disables blocking for the internet connection and, secondly, an array of questions which apparently will allow the parent to decide which types of content are permitted or not permitted through the same connection.

The wording is phrased as if this filtering can be decided on a per user basis rather than a per connection basis, but the type of filtering they are describing cannot be managed in that way. In brief the both types of filtering they are proposing are unworkable and dangerous. I’ll focus on pornography here because that is the main thrust of the campaign but the same points can be applied to other content types.

How do you define “pornography”?

You can’t (as the campaign does) try to get away with a dictionary definition because we are dealing with parents here who may well have their own idea of what is appropriate for their child to view. Limiting it to just ‘the explicit representation of sexual activity’ may not be enough.

As an example, if that were all that was being blocked, I still would need to check what my 8 year old was stumbling across on Google images - at which point the “protection” is not coming from the blocking, but from me. Additionally who decides what content fits into what category and what level of “risk” there is?

One parent may consider it perfectly acceptable for their child to see a scantily clad woman in a provocative pose, another may not and yet both would expect such a filtering service to meet their needs. It can’t. To be honest if it did have such a feature I could not see many taking advantage of it because it would be what a friend of mine refers to a “too much of a faff”.

How do the ISPs determine what gets blocked?

Certain websites will be obvious by their name/domain but is the government really so naive as to expect the site owners to be scrupulous in what they call their websites? Also what of images and content provided through otherwise innocent websites?

Google images for example has a safesearch option. Set that to “off” and your child will get a bit of surprise. But as the images are hosted and served by Google, the ISP cannot block them. So using the vaunted “network level” blocking, the explicit images can still be viewed. Other sites will be similar.

In the end the only way for an ISP to properly block explicit content is to do it on an image-by-image, video-by-video basis. To do that they’d have to either rely on peer reviews which are inherently slow to react or they’d need to employ people to check and grade the content.

Now I’m not an employment law expert but I’m pretty sure that an ISP employing somebody to view possibly illegal, often offensive and probably explicit material every day would be opening themselves up to legal consequences they could do without. This is something I cannot see any ISP being able to do properly. How long would it take before a parent brings an action against an ISP because their child was exposed to some piece of content which slipped through the filter?

Filtering does not work.

Anyone who uses filtering or blocking software will tell you that things slip through. Don’t believe me: how about your email spam filters? If they are so good why are you still suspicious of links in emails you weren’t expecting? If you are not suspicious, you should be.

Network level blocking means blocking sites and images before they get to your house. Such things already exist. I use a free (and very good) service called OpenDNS which – among others things – allows me to have it block websites that either declare themselves as “adult” or have been reported as such by other users of the service. Such sites are blocked before they even get down my phoneline. So this is pretty much what is being proposed here. It doesn’t work.

Well that’s not true, it does work, just not 100%. Google images is not blocked and other sites which have mixed content are not always blocked. If my daughter searches for “girls bedroom posters” on Google images with safesearch on “moderate” (the default setting by the way) she gets images which are possibly not what she was after. Filters can of course be too aggressive, such as the one I heard of recently which blocked access to the Essex Radio website (and presumably Sussex and Middlesex too). Lord knows what it makes of Scunthorpe.

The point again is that even with Google images safesearch on strict and OpenDNS I still have to monitor what my children surf. The main “protection” for my children comes from me, not any blocking software.

It’s all or nothing

The consultation allows for the fact that adults can request the ISP blocking is switched off either entirely or by specifying types of content. This sounds fine as long as all the adults use one connection and all the children use another. But that’s not how the world is. Those 73% of UK households with Internet access probably have a single main connection for each. Many of them have a mixed range of ages using the Internet.

So if a parent wants the blocking switched off, the child gets it switched off too. ISP blocking at “network level” is by definition all-or-nothing. Now you may argue that parents should not be watching such content if they have kids. But I’ll wager they do and if they have the blocking turned off, the children the proposed law seeks to protect are no longer protected.

It gives a false sense of security to parents

You’ll have gathered by now that this is my main point. The campaign raises concerns which all parents whose children have Internet access should consider. But the solution offered by the proposed law and consultation is poorly thought through.

As you have seen above, ISP blocking will still require a parent to monitor what their kids are surfing. This is good and I wholeheartedly agree that a parent/guardian is the best protection for children online. But what worries me is that this ISP blocking idea would cause a lot of parents to stop paying attention (or pay less of it) to what their children are doing online.

Let’s revisit the anti-virus analogy. Anyone running a Microsoft Windows PC should run anti-virus software, that is a given. But just having it there does not mean you will be “safe” from malware, phishing or other nasties. Ask anyone who supports Windows PCs and they will tell you that you are only as good as your last update. It’s the same with blocking or filtering. It does the best it can under the circumstances but it’s flawed.

It’s been suggested to me that I am not actually the type of parent this is aimed at. It’s a compliment to be considered so and there are parents out there who do not pay attention to what their children are doing online. The problem is that if that is the target market aren’t they exactly the ones who will presume this filtering alleviates them of any further concern to their child’s online activity? Doesn’t that put their children at greater risk? I’m not convinced that inadequate, impractical and unworkable filtering is a solution.

Oppose it

In the end, as shown above, ISP blocking would still require a parent to monitor their child’s online activity. That means the blocking is next to useless. Even if you presume it will help or do some of the job for you, you still run the significant risk that your child will find an image, video or site that you’d rather they didn’t.

As a Christian parent you might expect me to support this campaign, but I just can’t. I do believe that my children should not be exposed to certain types of material until such a time as they are ready to understand it, but I do not believe this is the way to achieve that.

The SafetyNet campaign might have the safety and protection of children at its heart but its using the wrong tactics. We do not need scaremongering, knee-jerk reactions based on shaky “evidence” and headline-grabbing phrasing. The government may use rhetoric which says it is trying to protect our children but the consultation is loaded and ill-thought out. Such a law, if passed, would not protect children any more than an 18 certificate on a DVD does. Educate parents, get them to speak to their kids, help them. Don’t make laws which would have a worse effect if passed.

What can we do

The Open Rights Group has provided ways to write to your MP on this matter. In addition if you are a parent or business involved in Internet Services you can take part in the government consultation. The closing date for the consultation is 6 September 2012.

Ryan Cartwright is a Christian and father of two. He works as a web developer and has been developing and hosting websites since 1996. A keen advocate of freedom he is evangelistic about and writes Free Software. He is a regular columnist (and sometime cartoonist) to Free Software Magazine (http://www.freesoftwaremagazine.com/poster/8833) and runs two websites of his own: Crimperman.org which a personal blog and Equitasit.co.uk which is for his web development work. You can find him on Identi.ca and Twitter as @crimperman.

Image: Bubble Reflection Cards CC-BY-NC-ND Flickr: Fellowship of the Rich

Remembering the Moon

Wendy Grossman looks back at what the landing on the moon meant and how our predictions of the technology of the future are never quite right: “Computers are… yesterday's future, and tomorrow will be about something else”.

"I knew my life was going to be lived in space," a 50-something said to me in 2009 on the anniversary of the moon landings, trying to describe the impact they had on him as a 12-year-old. I understood what he meant: on July 20, 1969, a late summer Sunday evening in my time zone, I was 15 and allowed to stay up late to watch; awed at both the achievement and the fact that we could see it live, we took Polaroid pictures (!) of the TV image showing Armstrong stepping onto the Moon's surface.

The science writer Tom Wilkie remarked once that the real impact of those early days of the space program was the image of the Earth from space, that it kicked off a new understanding of the planet as a whole, fragile ecosystem. The first Earth Day was just nine months later. At the time, it didn't seem like that. "We landed on the moon" became a sort of yardstick; how could we put a man on the moon yet be unable to fix a bicycle? That sort of thing.

To those who've grown up always knowing we landed on the moon in ancient times (that is, before they were born), it's hard to convey what a staggering moment of hope and astonishment that was. For one thing, it seemed so improbable and it happened so fast. In 1962, President Kennedy promised to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade - and it happened, even though he was assassinated. For another, it was the science fiction we all read as teens come to life. Surely the next steps would be other planets, greater access for the rest of us. Wouldn't I, in my lifetime, eventually be able also to look out the window of a vehicle in motion and see the Earth getting smaller?

Probably not. Many years later, I was on the receiving end of a rant from an English friend about the wasteful expense of sending people into space when unmanned spacecraft could do so much more for so much less money. He was, of course, right, and it's not much of a surprise that the death of the first human to set foot on the Moon, Neil Armstrong, so nearly coincided with the success of the Mars investigator robot, Curiosity. What Curiosity also reminds us, or should, is that although we admire Armstrong as a hero, the fact is that landing on the Moon wasn't so much his achievement as that of probably thousands, of engineers, programmers, and scientists who developed and built the technology necessary to get him there. As a result, the thing that makes me saddest about Armstrong's death on August 25 is the loss of his human memory of the experience of seeing and touching that off-Earth orbiting body.

The science fiction writer Charlie Stross has a lecture transcript I particularly like about the way the future changes under your feet. The space program - and, in the UK and France, Concorde - seemed like a beginning at the time, but has so far turned out to be an end. Sometime between 1950 and 1970, Stross argues, progress was redefined from being all about the speed of transport to being all about the speed of computers or, more precisely, Moore's Law. In the 1930s, when the moon-walkers were born, the speed of transport was doubling in less than a decade; but it only doubled in the 40 years from the late 1960s to 2007, when he wrote this talk. The speed of acceleration had slowed dramatically.

Applying this precedent to Moore's Law, Intel founder Gordon Moore's observation that the number of transistors that could fit on an integrated circuit doubled about every 24 months, increasing computing speed and power proportionately, Stross was happy to argue that despite what we all think today and the obsessive belief among Singularitarians that computers will surpass the computational power of humans oh, any day now, but certainly by 2030, "Computers and microprocessors aren't the future. They're yesterday's future, and tomorrow will be about something else." His suggestion: bandwidth, bringing things like lifelogging and ubiquitous computing so that no one ever gets lost; if we'd had that in 1969, the astronauts would have been sending back first-person total-immersion visual and tactile experiences that would now be in NASA's library for us all to experience as if at first hand instead of the just the external image we all know.

The science fiction I grew up with assumed that computers would remain rare (if huge) expensive items operated by the elite and knowledgeable (except, perhaps, for personal robots). Space flight, and personal transport, on the other hand, would be democratized. Partly, let's face it, that's because space travel and robots make compelling images and stories, particularly for movies, while sitting and typing...not so much. I didn't grow up imagining my life being mediated and expanded by computer use; I, like countless generations before me, grew up imagining the places I might go and the things I might see. Armstrong and the other astronauts, were my proxies. One day in the not-too-distant future, we will have no humans left who remember what it was actually like to look up and see the Earth in the sky while standing on a distant rock. There only ever have been, Wikipedia tells me, 12, all born in the 1930s.

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Image: Pacific Ocean from Space CC-BY-NC-ND Flickr: blueforce4116

A “Notice and Takedown” Regime Fit For Europe?

Ahead of the 5th September deadline for the European Commission’s consultation Saskia Walzel looks at the questions that need answering.

Next week the latest European Commission consultation on so called “notice and action” procedures for illegal content closes. The consultation is part of a new post-ACTA initiative to clarify the requirements for hosts to operate notice and takedown procedures across Europe. The legal underpinning for notice and action in the EU is the Article 14 limited liability provision of the E-Commerce Directive, which is vague to say the least.

Essentially an online host is not liable for the information stored or posted by users, if the host does not have “actual knowledge” of the illegal activity or information, and the host, upon obtaining such knowledge, acts “expeditiously” to remove or to disable access to the information.

In the absence of further details in the Directive, or the laws of EU member states, the notice and takedown procedures adopted by online hosts across the EU have become fragmented. The uncertainty about the circumstances under which a host obtains actual knowledge of illegal content, and how fast the host has to act, has led many hosts in the EU to remove content instantly on the basis of mere allegations. Following a failed attempt in 2010, the European Commission is now seeking to establish clarity and is encouraging citizens to respond to a questionnaire by the 5th September.

And there are some big questions the Commission wants answers to:

What is illegal content? Anything found to be illegal by a court: so far so easy. If a host is notified of a court order, the content should be removed. But, under Article 14, allegedly illegal content is also notified, for example in relation to possible copyright infringement or defamation. Because many hosts remove content following notification of alleged illegality, content which is perfectly legal has been removed.

What laws do apply? The E-Commerce Directive, obviously, and the laws of any given member state. But the type of illegal content the Commission is consulting on, such as copyright infringement, incitement to hatred or terrorism, child abuse, defamation and privacy, are not subject to fully harmonised laws across the EU. Laws on defamation and incitement vary widely across member states. Similarly member states provide users with vastly different copyright exceptions, such as for parody, quotation, criticism and review.

Should illegal content be removed EU wide? Only if is it is illegal across the EU. But if a court finds that content or a comment violates national incitement or defamation laws, which are not harmonised, it is difficult to see on what basis all EU citizens should be denied access. Should the Commission mandate hosts to operate country specific domains, such as .co.uk or .fr for EU wide services? Or should hosts be obliged to use geo-software which only prevents access to users with an IP address from a country where the content in question is considered illegal.

What safeguards are needed when allegedly illegal content is notified? At the moment there are none, notices don’t even have to contain an explanation as to why the content may be illegal under a given law. Users who have posted content have no right to file a counter notice before content is removed. Those who abuse Article 14 to file badly substantiated notices, or to force the removal of legal content, face no consequences or liability. Hosts cannot even refuse to play ball when someone has a history of filing bogus notices.

Should the EU adopt a DMCA type process? In 1998 the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act was passed into law, providing detailed guidance on how notice and takedown for allegedly copyright infringing content should be operated. The multiple ways in which the DMCA process has been abused has been well documented, but at least the DMCA is clear on what everybody has to do when. There are however alternatives. Brazil has decided in 2010 to only mandate notice and takedown if there is a court order to the effect that content is illegal, and Canada has just enshrined a “notice and notice” approach in its Copyright Modernization Act 2012.

Saskia is policy manager at Consumer Focus responsible for copyright policy. She tweets as @SaskiaWalzel

Image: European flag flying; Budapest Parliament CC-BY-NC-SA Flickr: soylentgreen

Dear Stihl: I’m Already Real, Thanks

Sarah Wanenchak analyses outdoor tool manufacturer Stihl's 'Get Real. Get Outside' advert series. She argues that these adverts question the legitimacy and worth of the whole of our relationship with our gadgets, and perpetuates an idea that digital technology is somehow solitary. As she says "Pretty gutsy for a chainsaw company."

A recent marketing campaign from outdoor tool manufacturer Stihl is a classic – and pretty obvious, for regular readers of this blog – example of digital dualism. It’s right there in the tagline: the campaign presents “outside” as more essentially real by contrasting it with elements of online life. It not only draws a distinction between online and offline, it clearly privileges the physical over the digital. And through the presentation of what “outside” is and means, it makes reference to one of the most common tropes of digital dualist discourse: the idea that use of digital technology is inherently solitary, disconnected, and interior, rather than something communal that people carry around with them wherever they go, augmenting their daily lived experience.

But there’s more going on here, and it’s worth paying attention to.

First, Stihl isn’t only privileging the physical over the digital – the ads not only make reference to Twitter and wifi but to Playstations and flatscreen TVs. In so doing, Stihl is actually drawing a much deeper distinction than the one between “online” and “offline”; it is not-so-subtly suggesting that contemporary consumer technology itself is somehow less real. Stihl is questioning the legitimacy and worth of the whole of our relationship with our gadgets.

Pretty gutsy for a chainsaw company.

And I’d argue that there’s something else beyond even that going on here. These ads don’t merely draw a distinction; they issue an imperative. They order the viewer to alter their behavior, to leave their technology behind and embrace a more “real” existence “outside”. This is not only fetishization of “IRL”, but fetishization of the pastoral – the assumption that there is something more authentic, real, and legitimate to be found in the natural world than in human constructions.

This is actually a very old idea, and it can be found in art and literature going back to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, especially in America (though I should note that Stihl’s ad campaign is Australian). America’s relationship with what has been culturally constructed as “wilderness” is a fundamental part of our historical national identity, and the industrial boom of the 19th century and the subsequent erosion of that wilderness made a mark on the American psyche. As Michael Sacasas writes in his essay on “The Smartphone in the Garden”:

America’s quasi-mythic self-understanding, then, included a vision of idyllic beauty and fecundity. But this vision would be imperiled by the appearance of the industrial machine, and the very moment of its first appearance would be a recurring trope in American literature. It would seem, in fact, that “Where were you when you first heard a train whistle?” was something akin to “Where were you when Kennedy was shot?” The former question was never articulated in the same manner, but the event was recorded over and over again.

Sacasas goes on to note that in art and literature that deal with pastoral themes, the encroachment of industrial technology is often presented with a certain degree of gentle threat or melancholy; it’s a kind of memento mori for rural American life, and a recognition that the world is changing in some fundamental and irreversible ways. Inherent in this is a nostalgia for the American pastoral, a sense that life lived within that context was somehow better and more real, as well as more communal. The pastoral was fetishized in much the same way that “IRL” is now, and its perceived loss was mourned in ways that should be familiar to anyone who’s read Sherry Turkle.

There’s an additional facet of this kind of thinking that’s worth pointing out: the idea that not only is human technology somehow separate from, in opposition to, and less real than the natural world, but that humans themselves are somehow divorced from the natural world. Lack of technology brings us closer to some vague construction of what we imagine as our true nature; use of technology takes us further away. In this understanding of us, we can exist in the natural world but we are not of it, and we can leave it. We aren’t animals. We aren’t inherently natural.

That’s about as dualist as you can get, I think.

What’s especially interesting about Stihl’s ads in this context is that they’re an outdoor tool company - they exist to make instruments through which a human being alters and remakes their environment. If we make use of dualist thinking for a moment and consider “real” as a spectrum, with the completely unconstructed and untouched by humanity as one end and the entirely technological and digital as the other, then a suburban backyard is hardly “real”. It’s a landscape that has been constructed entirely for human use, and ecologically speaking, it’s pretty much a desert (actually not even that, given the ecological richness of deserts).

Stihl is therefore building its ad campaign on some arguably flawed assumptions. But they’re powerful assumptions, and they draw on powerful elements in a lot of Western thinking about the relationship between humanity and technology. This indicates some of why digital dualist thinking is so pervasive; it’s much older than the internet or the smartphone. In order to truly understand what it is and where it comes from, we need to be sensitive to not only humanity’s relationship with technology, but how we’ve historically understood humanity’s relationship with what we perceive as the natural world.

This article originally appeared on Cyborgology.

Sarah Wanenchak (@dynamicsymmetry) is a PhD student at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her current research focuses on contentious politics and communications technology in a global context, particularly the role of emotion mediated by technology as a mobilizing force. She has also done work on the place of culture in combat and warfare, including the role of video games in modern war and meaning-making.

Image: Images from Andreas Stihl AG for Stihl Tools; Country: Australia; Released: February 2012

Look and Feel

Wendy Grossman gives some historical context to the current Apple v Samsung case -such as the software patent and copyright infringement lawsuits of Lotus and Borland- and looks at where innovation really stems from.

Reading over the accounts of the deliberations in Apple vs Samsung, the voice I keep hearing in my head is that of Philippe Kahn, the former CEO of Borland, one of the very first personal computing software companies, founded in 1981. I hear younger folks scratching their heads at that and saying, "Who?" Until 1992 Borland was one of the top three PC software companies, dominant in areas like programming languages and compilers; it faltered when it tried to compete with Lotus (long since swallowed by IBM) and Microsoft in office suites. In 1995 Kahn was ousted, going on to found three other companies.

What Kahn's voice is saying is, "Yes, we copied."

The occasion was an interview I did with him in July 1994 for the now-defunct magazine Personal Computer World, then a monthly magazine the size of a phone book. (Oh - phone book. Let's call it two 12.1 inch laptops, stacked, OK?). Among the subjects we rambled through was the lawsuit between Borland and Lotus, one of the first to cover the question of whether and when reverse-engineering infringes copyright. After six years of litigation, the case was finally decided by the Supreme Court in 1996.

The issue was spreadsheet software; Lotus 1-2-3 was the first killer application that made people want - need - to buy PCs. When Borland released its competing Quattro Pro, the software included a mode that copied Lotus's menu structure and a function to run Lotus's macros (this was when you could still record a macro with a few easy keyboard strokes; it was only later that writing macros began to require programming skills). In the district court, Lotus successfully argued that this was copyright infringement. In contrast, Borland, which eventually won the case on appeal, argued that the menu structure constituted a system. Kahn felt so strongly about pursuing the case that he called it a crusade and the company spent tens of millions of dollars on it.

"We don't believe anyone ever organized menus because they were expressive, or because the looked good," Kahn said at the time. "Print is next to Load because of functional reasons." Expression can be copyrighted; functionality instead is patented. Secondly, he argued, "In software, innovation is driven fundamentally by compatibility and interoperability." And so companies reverse-engineer: someone goes in a room by themselves and deconstructs the software or hardware and from that produces a functional specification. The product developers then see only that specification and from it create their own implementation. I suppose a writer's equivalent might be if someone read a lot of books (or Joseph Campbell's Hero With a Thousand Faces), broke down the stories to their essential elements, and then handed out pieces of paper that specified, "Entertaining and successful story in English about an apparently ordinary guy who finds out he's special and is drawn into adventures that make him uncomfortable but change his life." Depending on whether the writer you hand that to is Neil Gaiman, JRR Tolkien, or JK Rowling, you get a completely different finished product.

The value to the public of the Lotus versus Borland decision is that it enabled standards. Imagine if every piece of software had to implement a different keystroke to summon online help, for example (or pay a license fee to use F1). Or think of the many identical commands shared among Internet Explorer, Firefox, Opera, and Chrome: would users really benefit if each browser had to be completely different, or if Mosaic had been able to copyright the lot and lock out all other comers? This was the argument that As the EFF made in its amicus brief, that allowing the first developer of a new type of software to copyright its interface could lock up that technology and its market or 75 years or more.

In the mid 1990s, Apple - in a case that, as Harvard Business Review highlights, was very similar to this one - sued Microsoft over the "look and feel" of Windows. (That took a particular kind of hubris, given that everyone knows that Apple copied what it saw at Xerox to make that interface in the first place.) Like that case (and unlike Lotus versus Borland), Apple versus Samsung revolves around patents (functionality) rather than copyright (expression). But the fundamental questions in all three cases are the same: what is a unique innovation, what builds on prior art, and what is dictated by such externalities as human anatomy and psychology and the expectations we have developed over decades of phone and computer use?

What matters to Apple and Samsung is who gets to sell what in which markets. We, however, have a lot more important skin in this game: what is the best way to foster innovation and serve consumers? In Apple's presentation on Samsung's copying, Apple makes the same tired argument as the music industry: that if others can come along and copy its work it won't have any incentive to spend five years coming up with stuff like the iPad. Really? As Allworth notes, is that what they did after losing the Microsoft case? If Apple had won then and owned the entire desktop market, do you think they'd have ever had the incentive to develop the iPad? We have to hope that copying wins.

Update: Philippe Kahn notes that the ultimate cost of Borland vs Lotus through to the Supreme Court was $25 million over seven years. While it set an important precedent, he argues that it would favor Apple, and not Samsung. 29/8/12

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Image: Joystick-it tablet arcade stick CC-BY-SA Flickr: liewcf

Feature Interview: SciFund Challenge Part 2

"A science literate society would be where the public is connected to the science process." We feature the second part of ORGzine's interview with Dr Jai Ranganathan, co-founder of the SciFund Challenge crowdsourcing platform.

Following on from yesterday's Part I of ORGzine's interview with Dr Jai Ranganathan we conclude the discussion by talking further about who is funding the projects on the crowd-sourcing platforms, the problems of open access and how SciFund stands out from other similar platforms like Petridish. I recommend reading Part I to learn more about what SciFund is about.

Ruth: What is the demographic who are funding the projects? Is it the general public or other scientists?

Jai: It is all based on networks. We had a huge push out when SciFund happened. There was some group effect for being on SciFund. I would say that for the most part the money on SciFund came from the scientists own networks asking friends to ask friends and that sort of thing. So that is largely where they came from and building that audience is where you get started. The point here isn’t so much to ask for money it is to start a conversation.

So here is the model. The model is that scientists over the course of a year are on a regular basis reaching out with their science, giving public talks, blog posts -it doesn’t really matter what they are doing, it just matters that they are doing it on a semi-regular basis. And over the course of the year let's say they reach a 1000 people with their science message, some more some less interested. So then every so often you put a pitch out for cash and say 10 % of those people will kick up some bucks and get the science rolling. So that’s the model.

Imagine what that would look like if every scientists was directly connected to 1000 people Multiply that by all the scientists in this world. Wow. How many more people would be connected to science than they are now? This is what you call the virtuous cycle. You reach out to your audiences, not with a message saying "give me money", that is not a winning message. The message is just your science and every so often, whether or not people give money, there are still more people paying attention.

Ruth: So do you have a similar model for how the message gets back out to the people when they are finished with the project? Are you using a Creative Commons license or passing the research back to those who backed the project originally?

Jai: It is definitely something we are considering for the next round, requesting that people make their science available through open access. We do that ourselves with our research and that we are publishing through PloS One, which is an open access journal, about SciFund and what we are doing and all our results are published on our blog as well.

But for other scientists it is their call. We are also asking whether we want to make open access a requirement to be involved. Now as you know most/all open access journals they charge -it is an author pay model so that, for example, for PloS One to publish a paper costs $13000 and so if you look at the amounts being raised through SciFund they are still small for scientists - in the thousands range. So that is the tension there. If people were raising $100,000, then making it a requirement to use open access would be an easier requirement, but at this point where it still costs money and they don’t have an extra $15000 lying around -that is definitely a tension at this point.

Ruth: But something that you may discuss with the next wave of scientists?

Jai: It is absolutely the case that open access is super-connected to what we are doing with crowd-sourcing. And we definitely want to recommend it. The question is how do we make things more alive?

Another movement that is connected is open notebook science which is where scientists are publishing their results, prior to their papers being published, on blogs or open forums. So publishing as it happens in real time. We can model that in SciFund. We have been pushing our results out to everyone.

Ruth: If you publish as you go along does it also encourage people to publish failed results? With the crowd-funding style is there a possible sense of disappointment if the results are not those that were expected?

Jai: I think the first thing is that crowd funding for science is different to say crowd-funding for a band. It is very common for a band to put up a request to get recording time for a new album and so the product there is the album and if they don’t make the album the thing is a big bust.

The model is different for science. So say we are going to go out Borneo and study orang-utans and publish our results about it. Well the product there, at least as far as the public are concerned, as far as I am concerned, isn’t that final paper about orang-utans it s the connection to the scientists over time. Science is the process and the results are just the by product. The product is finding out how the science happens. I don’t think there is a real sense of failure, unless the scientists doesn’t do anything but most scientists are workaholics so I don’t think there is much chance of that.

Ruth: I like the idea of creating a community between scientists and the general public and I think this is very worthwhile.

Jai: The question is what is a science literate society? And the general response is 'people know more facts', but I think that is the wrong way of thinking about it. I mean I have a Ph.D. in Biology but I know less than nothing about Physics. You know the world of science is too big. Too many facts to know. I think a better way, a more useful way, for a science literate society would be where the public is connected to the science process.

You know the science process is considered a state secret. I only first knew what the science process was when I was in my Master's for God's sake. So here is my vision of the future. A person is following a scientist on a semi-regular basis and sees how their science is done and in the process learns about the scientific method. What is the scientific method about other than being transparent about what you are doing, and having people check your work? That’s it. So say they are following a physicist and hey hear something in the news about some anti-vacine nonsense and they say 'wait a minute I don’t know anything about Biology, but I do know the scientific process and this isn’t that. This seems like something different.' And that's the whole point to connect people to the science process.

Ruth: One of the other things I was wondering is, as an American based site, do you offer opportunities for people from other countries to use the same process?

Jai: Oh yeah we have had people from 12 different countries as part of the last wave of projects. People from UK, people from Europe, people from New Zealand, Australia, people from all over the place.

Ruth: That's excellent. To me science should be internationally focused.

Jai: It's funny you should say that as the best example for science crowd funding is based in the UK.

You know about Cancer Research UK right?

Ruth: Yes

Jai: Well do you know about their crowd-funding? - I'll send you the link to it. Well they are the leaders as far as I am concerned. They feature specific research projects on their site. It's not like 'raise money for breast cancer research' it is this scientist is working on a gene... It is funding the core science directly. They are, on a very regular basis, raising £50 thousand, £100 thousand, not for breast cancer generally, but specific scientists on specific cancer related work. The reason they are able to raise those kinds of dollars, or pounds, is because it is not drawing off at a network for the scientist, but drawing off the network support of Cancer Research UK.

Ruth: How do you feel about similar science-based projects like Fundageek, Petridish and Peerbackers? Do you see yourself as providing a different type of crowd-sourcing or do you see all of these projects as simply contributing to an increased interest in science ?

Jai: I think at this point the more the merrier because there are so good ones, some bad and some medium ones and so the more the merrier frankly.

Ruth: I was just going to finish by asking you where you see the future of the SciFund challenge?

Jai: Well for now we are just going to keep going in this rounds fashion.

Ok, just to back up a moment. You asked 'what makes SciFund different?' and I think there is something which makes SciFund very different from any other crowd-sourcing platform. It is that we set this up very much on the values of scientists engaging online and making a community. And I should say that, by the way, SciFund is not a business, we are not making any money off this. We are all working for for-profit organisations, but SciFund itself doesn’t make any money.

The people really responded to our mission. If you look at the values of a science online community it is all based on transparency and engagement and support and that is what we are all about. So if you look at every other site each project is on its own. On SciFund you are not on your own because all the SciFund scientists are helping each other because everyone needs help. If you are making science that is great for the general public you are going to need help with that -everyone does. So for SciFund we make it very clear that it is a group exercise.

If there is anything that makes SciFund different it is the philosophy that we all rise together.

Ruth: This has been really interesting and it has been great speaking to you. Thank you very much.

For more on SciFund check their blog and find Dr Jai Ranganathan's tweets at @jranganathan.

You can follow Ruth as zine Editor on @ORGzine

Feature Interview: SciFund Challenge Part 1

"If there is anything that makes Scifund different it is that we all rise together" Jai Ranganathan, co-founder of the SciFund Challenge, kindly agreed to be interviewed for ORGzine and spoke about how their crowd-sourcing platform works and what its real purpose is.

"The legislature is considering a ban on climate change, to make sea level rise illegal, and this is the result of a science- illiterate world"

Dr. Jai Ranganathan, co-founder of the SciFund Challenge, explained how his 'crowd-sourcing for science' platform is filling a real need, not just for science funding, but for the general public to become involved in science. He answered questions to ORGzine Editor, Ruth Coustick, on peer-reviewing, how scientists can attract a crowd, and where this platform differentiates from all others. His answers were enthusiastic and in-depth, keen to emphasise that SciFund Challenge has a lot to offer and showing a real sense of pride in the platform.

Ruth: Could you start by telling us what the SciFund Challenge is?

Jai: So what the SciFund challenge is an answer to two problems. If you look at science today there are two giant problems. The first, which I think is the most important, is that, particularly in the United States (and in culture world-wide), the gap between science and society has never been more due disastrous consequences. If you look at the lack of movement on climate change - in the US state of North Carolina the legislature is considering a bill to ban on climate change, to make it illegal, to make sea level rise illegal - and this is the consequences of a science illiterate society and a science illiterate world in many ways.

There has been much written about it, why we are in this situation. One of the reasons why is because scientists don’t talk to general audiences, they just don't. So that's the first problem.

The second problem is that funding for science across the developed world is getting harder and harder to come by. Maybe crowd funding for science is the answer to both because for the first time

it is about cash, but you can only get that cash by connecting to the crowd; crowd funding - the crowd comes first. So maybe this is the way for the first time to change the structure of academia so that there is a reason to connect with the general public.

And again it's not a bribe, it not 'oh you talk to these people and get $50 out of it'. It's not that at all. It's a way to change the incentives so that we to close this gap and raise micro-science along the way. That’s what SciFund is about.

Ruth: If scientists have to get a crowd, how do they do it? Unlike media-based crowd-sourcing platforms, most scientists don't have a big fan following to start with, not generally.

Jai: Well you are exactly right because the amount of money you raise is directly dependant on the crowd you have. There are particular reasons why scientists don't engage. The first is a lack of money. The second reason is a lack of understanding. How you do this? How do you create a good three minute video? How do you put out your science in an interesting and engaging way? Cutting out the jargon, but not losing the heart of the science -how do you do that?

So once you have figured out how to do that -how do you find an audience to reach out to? That’s what scientists don't know for the most part how to do. So that's what SciFund Challenge is really about. What it is really is is a crash course in modern communications for scientists packaged as a money-making scheme. But the money really isn’t the point; the point is really this communications course as to how you do this. As it turns out all the things you need to do for a successful crowd funding campaign - have a good video, have engaging text, good photographs, talk to people on Twitter -you have to do all of those things anyway if you are trying to reach people with your science message. So that's what SciFund is trying to solve.

Ruth: What has the reaction been like from other scientists to the project?

Jai: It has been surprising. We have been really shocked by how positive people have been. You know science is a very conservative institution, not conservative in a political sense, but conservative in a 'not necessarily moving quickly with societal trends' sense. So when we started this about a year ago myself and my partner Jarrett Byrnes, he and I are both ecologists, we were not sure if we would be able to get very far or if the wave of opinion of scientists would shut us down by saying 'oh you can't do this', 'this is just wrong', 'it is against what science is about', 'blah. blah blah'. In effect that hasn’t happened. The response has been hugely positive. We have run now 2 waves and about 130 scientists through and there have been many many more scientists who have said 'We can't do this now, but we are definitely paying attention'. It has been really amazing how open people have been.

Ruth: So what criteria do you use to decide what projects will go up on the site?

Jai: This is a run in a group fashion. We run these in rounds. The reason for this is so people have other people to help with their projects, because SciFund is about helping each other and we need a big group for this to work. Our role is to make sure that the science is legitimate, but beyond that everyone gets in.

I think there is a big difference between our crowd funding and Kickstarter, for example, and crowd funding for music or film or that kind of thing because you know with a band you either like the band or you don't. The danger with something technical like science is that you can have something with a flashy video, but the science behind it is either fraudulent or nonsense. We want to make sure we keep that out. So in the second round of SciFund we used a volunteer peer review system of scientists running the proposals, and every scientists had to write an abstract of about 200 words just to ensure that stuff was on the level.

The aim is not to pick the best science, that's not the point. We had very specific criteria.

The criteria is:

-The project must not be fraudulent. You are not trying to cure Alzheimer's disease with crystals, nothing like that.

-It has to be within the bounds of reality of your discipline, so no perpetual motion machines

-It also has to be real. It has to make sense. Trying to raise $2000 to go to your field site in Africa? Well that makes sense - you can see how that would work. Trying to raise $2000 to build a particle accelerator? - That's not going to work.

I would say it is a pretty loose filter, just to make sure everybody is on the level.

Ruth: It is interesting that you are still using a form of peer review. When I first heard of SciFund there were people responding with cynicism that it wouldn’t have the same level of quality of science. I once saw a person saying it would be "all polar bears and no bacteria" -that the science would be all populist.

Jai: In fact that hasn't been true at all. Some of our best projects, some of our best funded projects, have been people working on mouse duct bacteria and projects looking at core ecological statistics. We run SciFund as an experiment and we collect tons of data on the way. We publish results on our blog and in literature discussing what it takes to get funded. And ultimately what it takes is your messaging. Can you create a compelling message about your science? And I fundamentally believe that you can create a compelling message about all science. Now, is it slightly more achievable if you are working on tigers or polar bears? Of course. You can do it all for science. And the proof is we have got a 135 projects through and it wasn’t 'oh I am working on polar bears' and get funded. It wasn’t like that at all. It really is just about getting the compelling message across.

The remainder of this interview addressing how it works as an international platform, the character of the funder and how it is different from Petridish and Fundageek will be published on ORGzine tomorrow.

Image: CC-BY 2.0 Amy Loves Yah

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.