First-mover disadvantage

Amazon has just unveiled a feature that Mp3.com were sued on copyright breaches for introducing in 2000. Wendy M Grossman asks why some companies have success with new technologies and others fail.

News stories alerted me this week to a new feature of my 17-year-old Amazon.com account: the site will load up a cloud music area with MP3s of all the CDs it knows you've bought so you can play them wherever and whenever. I went and looked. Sure enough, Amazon knows, or thinks it knows, that I own, or at least have bought, 161 CDs, and it rapidly populated my account with the MP3s from those discs. All I have to do is push buttons to listen to them any place, any time.

How 1999.

Those with long memories may remember Michael Robertson's MP3.com, one of the earliest sites to do retail digital music (not first - that was the Internet Underground Music Archive). Founded in 1997, the site focused on indie bands and artists - people who didn't have hostile record labels to make trouble. The company went public in 1999 with, a trendy dot-com-boom triple first-day pop. In January 2000, the company announced My.MP3.com. It worked like this: you put a CD in your computer's drive to confirm you owned the disc, and thereafter the service would allow you to play MP3s from that CD any time you liked.

Instant lawsuit! MP3.com's argument - which it subsequently made in court - was that there was no copyright infringement since you could only play the MP3s if you had a physical CD to unlock access (glossing over, I suppose, the possibility that you had borrowed or copied one). The record companies, however, focused on the fact that in order to provide this service MP3.com had to create its own database of MP3s by ripping all those thousands of CDs. Ultimately, they were successful in arguing that creating that database was not fair use. The resulting settlements crippled the company and it was finally taken over by Vivendi (and then the domain name was sold to CNet, which means it now belongs to CBS, but that's a whole 'nother story).

It's patently obvious that Amazon is not going to be taken down over what is essentially the same service (for one thing, the company already has MP3 copies of most CDs under license, since it is already a significant digital music retailer in its own right). During the dot-com boom people used to talk a lot about "first-mover advantage", the notion that the first into a market could run the table and get so far ahead of later entrants that they will never catch up. It worked for Amazon.com, eBay, and Paypal, for different reasons. all services where contractual agreements with suppliers and client servers or creating a pooled mass audience were difficult to duplicate for later entrants, just as a new entrant into car-sharing would find it hard to get enough parking spaces in urban areas to compete with Zipcar. The strategy even worked for Yahoo! only until something way better came along. But if you're too far ahead of your time - especially if you're small - you run into the MP3.com problem: other people may not understand.

There are lots of examples of technologies and services that failed because the inventors were too far ahead of their time: the many early 1990s efforts at digital cash, Go's 1987 pre-tablet effort at pen-based computing. Usually, these efforts are defeated by either the state of the technology (for example, they function poorly because there isn't enough processing power or cheap storage space) or the state of the market (not enough people online, or too few people understand the technology you're asking them to use). But My.MP3.com was an example of something that failed because of the state of the law. At its launch at the beginning of 2000, the original Napster was perhaps a month old (and already being sued by the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA)), and iTunes was more than a year from its first outing. It was a time when the record companies had yet to accept the Internet as a medium that, like cassette tapes before it, could provide them with a new marketplace.

Now, of course, everybody knows that. According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI)'s own figures from its 2012 report, in 2011 the number of countries with major international music services nearly doubled. Global record company revenues grew by about 8 percent to $5.2 billion, and the number of paying subscribers rose 65 percent to 13.4 million worldwide. You have to wonder: what if they had made deals with Napster, and let My.MP3.com go ahead instead of suing them out of existence? They might be years further ahead in terms of revenues, and be spending far less time and money pursuing file-sharers - not that there would be no illegal file-sharing, but there would almost certainly be much less of it, and there'd certainly be much less residual anger among the recording industry's best customers.

It's also clear that size matters as well as timing: Amazon, like Google Books, is too big to kill. Little guys you can prosecute or sue. Big guys, you have to make deals. Although: the biggest price consumers paid for the loss of My.MP3.com wasn't really that service but the rest of the site's function as a hub for independent artists.

I don't know Michael Robertson. But if I were in his shoes, I imagine I'd be shaking my head and going, "Damn. We did that 13 years ago. Why didn't they let us?"

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series.

Censoring Pirate Sites Doesn’t Work, Researchers Find

Does censoring "pirate" sites reduce the availability of pirated content? Not necessarily, says Ernesto.

A new study released by researchers from Boston’s Northeastern University shows that censoring “pirate” sites by blocking or seizing their domains is ineffective. The researchers looked at the availability of various pirated media on file-hosting sites and found that uploaders post more new content than copyright holders can take down. A better solution, according to the researchers, is to block the money streams that flow to these sites.

The file-sharing landscape has often been described as a hydra. Take one site down, and several new ones will take its place.

Blocking or censoring sites and files may have a short-lived effect, but it does very little to decrease the availability of pirated content on the Internet.

Researchers from Boston’s Northeastern University carried out a study to see how effective various anti-piracy measures are. They monitored thousands of files across several popular file-hosting services and found, among other things, that DMCA (Digital Millenium Copyright Act) notices are a drop in the ocean.

The researchers show that file-hosting services such as Uploaded, Wupload, RapidShare and Netload disable access to many files after receiving DMCA takedown notices, but that this does little to decrease the availability of pirated content.

Similarly, the researchers find evidence that the Megaupload shutdown did little to hinder pirates. On the contrary, the file-hosting landscape became more diverse with uploaders spreading content over hundreds of services.

“There is a cat-and-mouse game between uploaders and copyright owners, where pirated content is being uploaded by the former and deleted by the latter, and where new One-Click Hosters and direct download sites are appearing while others are being shut down,” the researchers write.

“Currently, this game seems to be in favour of the many pirates who provide far more content than what the copyright owners are taking down,” they conclude.

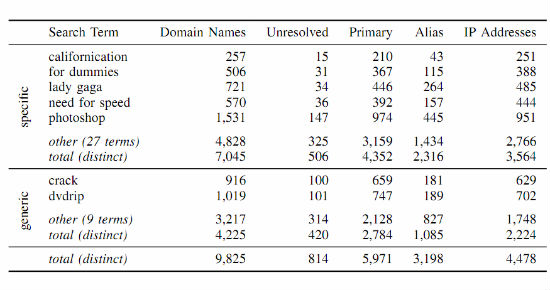

The study also looked at the number of sites where copyrighted content is available. The researchers scraped the popular file-hosting search engine FilesTube and found that there were nearly 10,000 distinct domain names and 5,000 IP-addresses where alleged pirate content was hosted.

For example, a search for “dvdrip” returned results on 1,019 different domains using 702 distinct IP-addresses.

From the above the researchers conclude that anti-piracy measures aimed at reducing the availability of pirated content are less effective than often suggested. A more fruitful approach, they argue, may be to take away their ability to process payments, through PayPal or credit card processors.

This is already happening widely , especially with file-hosting services that offer affiliate programs. However, as the researchers rightfully note there are also many perfectly legitimate file-hosting services that operate within the boundaries of the law and can’t be simply cut off.

The researchers end with the now common mantra that when it comes to online piracy, innovation often trumps legislation.

“Given our findings that highlight the difficulties of reducing the supply of pirated content, it appears to be promising to follow a complementary strategy of reducing the demand for pirated content, e.g., by providing legitimate offers that are more attractive to consumers than pirating content.”

In memory of Aaron Swartz

Computer programmer and internet activist Aaron Swartz committed suicide on Friday, 11 January.

Swartz was famous for developing the RSS software and helping to code news aggregation website and internet forum Reddit. He is primarily remembered, however, for his struggle for open access to information and the protection of digital rights. Lawrence Lessig, academic scholar on copyright issues and Swartz’s friend said, “Aaron had literally done nothing in his life 'to make money' . . . Aaron was always and only working for (at least his conception of) the public good."

In July 2011 US Attorney for Massachusetts, Carmen Ortiz, charged Swartz with downloading four million academic journals from digital library JSTOR, in order to make the documents public. The authors of the articles on JSTOR do not receive the money paid by academic institutions to view their work, instead this money goes to the publishers. Despite the fact that JSTOR dropped its case against Swartz, after being assured he would not be distributing the documents, the prosecution continued. The charges carried a maximum sentence of thirty-five years and a fine of up to one million dollars. It is important to note that the documents in question were available for free on Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s campus in digital form.

The government was repeatedly criticised for its overzealousness of the use of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Its anti-hacking provisions were interpreted to include violations of a website’s terms of service or policy. This left millions of internet users guilty of engaging in criminal conduct, according to a federal appeals court.

Lessig pondered on the prosecutors’ obsession to brand him a felon, “Near the end, due to this overwhelming and expensive case, Swartz ended up spending all the wealth he had accumulated from his past achievements, while at the same time slumping deeper into the depression that eventually took his life.”

A few days after Swartz was charged, Greg Maxwell used JSTOR, legally this time, to download more than 18,000 scientific papers, and make them available to the public via The Pirate Bay. In a manifesto accompanying the 33 gigabyte upload, Maxwell proclaims, "As far as I can tell, the money paid for access today serves little significant purpose except to perpetuate dead business models. The 'publish or perish' pressure in academia gives the authors an impossibly weak negotiating position."

He argues that transparency and free access to scientific knowledge should be encouraged since they will only benefit humankind as a whole. The purpose of US copyright was to enhance progress in the arts and sciences, not suffocate it in the industry’s vice-grip. Critics of the legislation under which Swartz was arrested are suggesting that there is something fundamentally broken about something which forces young, talented individuals to tip-toe around tenuous laws, “hiding hard-drives in closets in order ask basic and important questions about our work”.

Shortly after Maxwell’s actions JSTOR announced they would be making all of their public domain material available free of charge. They said his actions were influential in that decision, but they already had plans to do so.

Swartz, Maxwell, and other hacktivists’ actions have not been ignored by more powerful actors. In July 2011 the European Commission launched a call for a public consultation how research data could be more available and scientific journals more readily available. Their goal is for 60% of European publicly-funded research articles to be available to everyone by 2016. 84% of those questioned believed that there is not adequate free access to research journals and only 25% of researchers share their work publicly.

In addition, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an American non-profit organisation similar to ORG, has used Swartz’s death as a rallying call for reform of computer hacking laws. They claim the laws are both too broad, and too vague to be proportional to the harm caused, with punishments too severe for what are essentially victimless crimes. In particular, the EFF mentions the case of United States v. Drew. The Act’s vague use of the word “authorisation” allowed the state in this case to attempt to prosecute by claiming that violating the terms of use of the website was deemed as “unauthorised access”.

To go back to Swartz, Lessig called his prosecutors bullies, that is accurate. The playground, however, is much bigger, and the bully has a lot more at his disposal than his bare fists. There needs to be more of a public outcry against knee-jerk reactions to stifling free access to information, or the Great Firewall will extend far beyond China. In the words of Swarz’s family, “Aaron's death is not simply a personal tragedy. It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach. Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney's office and at MIT contributed to his death. […] Today, we grieve for the extraordinary and irreplaceable man that we have lost.”

In a beautifully fitting tribute, academics have banded together on Twiiter with the hashtag #pdftribute to upload their work online, free of charge.

Symbiosis

“For free content to survive, advertising has to find levels and techniques consumers can tolerate.” Wendy M Grossman questions the extent to which blocking adverts benefits the user and argues that we need more control about what adverts we see than the current options of all or none.

It's long been obvious that there's a genuine problem with respect to advertising both online and in older media. The more invasive and frequent ads get, the more consumers take action to insulate themselves by blocking, bypassing, or editing. It is clear, for example, that at least some of the success of video recording is the ability to skip or fast-forward through commercials. Yet consumers also expect to be able to access a great deal of new content either for free or at an aggregate price that means that no one piece of it costs much.

Advertising as a business model worked for a long time, in part because the market was divided up into a small number of relatively large audiences with relatively few alternative choices. Today's market continues to fracture into smaller and smaller pieces, and as the rates content owners can charge drops accordingly, they get desperate to replace the lost revenue. And so US television gets 22-minute half hours, the London Underground gets video billboards, and news web sites display moving ads that (deliberately) draw the eye away from the thing you're trying to read, making it impossible to concentrate.

The result is an arms race between frustrated consumers and angry content owners and advertisers. Consumers block ads by installing browser plug-ins; sites such as cbs.com retaliate by refusing to play video clips to anyone blocking ads. Industry responds with DVRs optimised to skip ads and fast forward buttons, and sometimes gets sued as a result. At the industry level, however, the game looks a little different. You might call it "Who owns the audience?"

At the beginning of January, the French internet service providerFree, sent out a firmware router update that added a new feature that blocks ads for its subscribers. If you want ads, you can get them, but you have to opt in. This week, the French minister for the digital economy, Fleur Pellerin, told it to stop.

I'm sure Free thought it was taking a popular approach. As the above-linked article notes, the Firefox extension Adblock Plus alone has 43 million users worldwide, even operating under the disadvantage that users must learn about, locate, and install it. For that many people to take that much effort to buck the system means real and widespread discontent with the status quo. A smart ISP trying to compete might well see default ad-blocking as a unique selling point, at least in the short term; longer term, for free content to survive, advertising has to find levels and techniques consumers can tolerate.

However, as Deutsche Welle points out, this case is also a twist on the kinds of debates we've seen before, first in disputes between cable companies and TV networks, and more recently framed in the online world as network neutrality. Ultimately, this is about who pays. Should Google, whose business relies on the ability of billions of people to reach their services via their internet connections, pay ISPs and mobile network operators for delivering that audience to it? Or should ISPs and mobile network operators regard Google as a major reason people bother to subscribe to their services in the first place? Which one is the opportunistic parasite?

Those of us who do not work for either side probably would say neither. Instead, it's more reasonable to see all these large companies as interdependent and all benefiting from the relationships in question. Symbionts, not parasites at all. So far, despite various loud demands and threats at various times, the industry has generally behaved as though it agreed. Bandwidth-swamping video, however, always had the potential to disrupt that, not least because the cable companies that deliver internet services also deliver television (just as the telephone companies were the ones complaining when internet telephony became popular). In France, however, there is some precedent for seeing Google as the unfair beneficiary; Deutsche Welle notes that last year Google began paying the country's largest ISP, Orange, for some of its traffic. In a larger piece on the many points of failure in online TV viewing, Gigaom points to a possibly similar spat in the US between Netflix and Comcast. There, however, there is the added complication of the First Amendment, which protects even commercial speech.

In any event, blocking ads at the router level offers consumers mixed benefits. You don't have to see ads, great. However, that also means rendering some sites inaccessible. Most notably, anything owned by the US TV network CBS refuses to display content to anyone blocking ads (my doped-up Firefox can't load CBS subsidiary ZDNet, and the home of a friend whose router blocks all ad networks is practically a news-free zone). Browser-based blocking can be easily turned off or bypassed; for technically unsavvy consumers router or ISP-based blocking is a blunt instrument of mass destruction. It's not censorship, since lost sites are not being specifically targeted for disruption. But it benefits no one to have sites unpredictably drop out of availability. For free content to survive, advertising has to find levels and techniques consumers can tolerate.

It pains me to say that Free's approach is wrong because I hate so many online ads so much, but it is, because as I've seen the system described it is only user-configurable in the broadest sense: on or off. Users need more and finer-grained choices than that.

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

The antitrust time warp

Wendy M Grossman discusses how slowly the government reacts to changes in the internet and finds out what happens when she tries to use her Android without relying on Google Play Store.

Government antitrust actions are typically a generation behind when it comes to something as fast-moving as the Internet. They can't help it; they're supposed to wait for evidence of actual harm. So when the issue was Microsoft tying things to Windows, the EU was still fretting about media player in 2004 and Internet Explorer in 2009.

This week, the US Federal Trade Commission announced it has found no evidence that Google exercises search bias at the expense of its competitors. However, the FTC did decide the company had misused some of its mobile phone patents and Google has agreed to let sites opt out of having their content scraped for reuse.

These things do matter – and it's churlish to complain that a government process designed to be slow and careful is…slow and careful - but they are at the very least incomplete: I'm less concerned about Microsoft's and Motorola's ability to compete with Google than I am if all of them lock out smaller companies. The FTC's requirement that Google stop preventing small companies using its advertising platform from signing up with competitors' platforms is to be welcomed. But for many consumers the battleground has already moved and the casualties as these large companies shift strategy to win at mobile and social networking will be all of us.

This week the Wall Street Journal highlighted Google's strategy of aggregating material onto Google+ pages in ways users do not expect. The integration of that service across all of Google's products is increasing every day, exactly as privacy advocates feared when the company coagulated its more than sixty privacy policies last year. At the corporate level this is, the Journal suggests, necessary for Google to compete with Facebook. Most consumers, however, use the two services for completely different reasons: we sign up for Facebook to share information with friends; we use Google services for specific tasks.

Then there's mobile. For the last month or so, I've been experimenting to see how far I could get with my new Android phone without tying it to a Google account. (I don't like feeling pwned.) On the one hand, the phone is perfectly functional: you can do all the things you actually bought the phone for, like email, SMS, phone calls, web browsing, reading, listening to music, and taking pictures. What you can't do is download apps, even free apps without a Google Play Store account. Finding them elsewhere means increased risk of malware. Running anti-virus software on your phone, however, requires you to download the app from the Play Store. Or the Samsung app store, which, requires you to accept its privacy policy even just to search and to create an account if you want to download anything. Upshot: the security of this device, the class that is increasingly being targeted by cybercriminals, is dependent on our agreeing to tracking, to providing data for marketing purposes, and to any other conditions they care to impose. This sounds like a protection racket to me.

As Chris Soghoian (among others) has pointed out, the default settings for such things matter; most people will use what's put in front of them. So I note, for example, that on Android the only web browser provided is Chrome, and within Chrome you can only choose Google, Bing, or Yahoo! as your default search engine. Adding DuckDuckGo, my default search engine of choice, requires me to root the phone to hack Chrome and violate the warranty or download a different browser, which means signing into the Play Store. (Actually, I did find a way to download Firefox onto my desktop, run it through an anti-virus checker there, and then transfer it to the phone for installation; but how many people are that stubborn?) Which means, accordingly, that the long tail of search engines might as well not exist for most Android users. How is this different from Microsoft and Internet Explorer in the early 2000s?

Note: this is not a subsidised phone. I bought it retail. If it's not going to be free as in beer, shouldn't it be at least a bit free as in speech?

Elsewhere, this week saw an interesting exchange between Evgency Morozov at the FT and Andrew Brown at the Guardian regarding Google Now. Morozov argued that in aggregating everything Google knows about you and delivering little nudges to be a "better person", such as a note of how far you've walked in the last month, it's becoming a corporate nanny on a scale of intrusiveness that a government could never get away with. Brown explores the human limits of that approach.

For the purposes of net.wars a more significant point is that Google Now demonstrates precisely why making informed decisions about our privacy is so hard. Whoever thought, when signing up for and diligently read the privacy policies of Gmail or Google calendar, or an Android phone – or even did all three and creating a Google+ page – that their data would be aggregated in order to chide you into walking more or that your Google+ page would suddenly assemble your various disparate postings across the Net as part of your profile?

These are the issues of 2013. And sadly, the FTC and the EU most likely won't get to them for another five years.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series.

What Users Say and Do About Intellectual Property

Jabed Tarapdar writes up the discussion from the 'Copyright in the Digital Age: What Users Say and Do About Intellectual Property' event, which focused on new evidence from the University of Leeds.

Executive Director for Open Rights Group, Jim Killock calls for policy-makers to make 'more effort to understand the perspective of the user' during the policy-making process

The event 'Copyright in the Digital Age: What Users Say and Do About Intellectual Property' was held on 28 November 2012. The discussion focused on recent research by University of Leeds. ORG's Executive Director Jim Killock gave one of the key note responses. You can see notes from his talk at the ORG website.

Representatives from the University of Leeds argued that if copyright legislation is to be successfully implemented, it is crucial that users understand and agree with it, otherwise people may find alternative ways to undermine the law. The research discovered that at the moment 'half of all internet users are unsure if they are using the internet legally', leaving copyright law in 'disrepute'.

Jim Killock explained that the law does not really reflect the norms and expectations of internet users because, during negotiations over copyright law, policy makers have not made enough effort to understand the perspective of the user.

UK copyright law makes it absolutely clear that unauthorised file-sharing is illegal.

However, Killock highlighted the findings that people often have a different understanding of what activity is acceptable or fair. For example, the research suggests users tended to believe that sharing between family members is normal and fair, whereas, illegal selling is not fair and clearly illegal.

So how can this situation be improved?

Chief Executive of PACT, John McVay noted, under current proposals within the Digital Economy Act 2010, letters will be sent to customers for alleged copyright infringement. These letters will explain how their actions may have conflicted with copyright law.

Helen Goodman MP stated 'education is only one strand' of successfully protecting creators' material. What if they disagree with the message? These letters will not be useful if they counter user norms. She also noted that streaming could help tackle illegal downloading.

The research by University of Leeds argued 'copyright is a social thing. The user should be seen as a partner who can help the industry survive'. However, it was suggested that under the current system, people are unwilling to support the industry because they see some elements as illigitimate.

If McVay is correct and 'royalties are spread to all workers', this has to be made clearer to the public.

Copyright law is also neglecting users' various uses of copyright material. There was plenty of disagreement over policy-makers' proposals for a parody exception to copyright.

Killock explained, for example, that the absence of a parody exception has meant campaigners cannot offer the most effective critical commentary. Such use should not depend on the consent of the person who created the original.

However McVay countered, the creator has the moral right over the intent of their work. He gave as an example 'the use of an anti-war song as a pro-war parody' will offensively undermine the original intended message.

But according to Killock, supporting parody in law will ensure copyright does not work as a sort of veto over economic and socially useful activity.

Killock suggested that policy-makers' lack of understanding of users stems from their attention being focused on trade associations during discussions over copyright law. 'Trade associations and technology groups' play a major role during copyright policy-making. The Digital Economy Act is one example of policy-makers paying little attention to wider interests.

Killock concluded successful copyright law depends on policy-makers taking into account the public interest and running a more open and inclusive policy making process.

Grabbing at Governance

Internet governance: what’s the situation and how is it evolving? Wendy M Grossman explores these questions in light of the coming World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT).

Someday the development of internet governance will look like a continuous historical sweep whose outcome, in hindsight, is obvious. At the beginning will be one man, Jon Postel, who in the mid-1990s was, if anyone was, the god of the internet. At the end will be…well, we don't know yet. And the sad thing is that the road to governance is so long and frankly so dull: years of meetings, committees, proposals, debate, redrafted proposals, diplomatic language, and, worst of all, remote from the mundane experience of everyday internet users, such as spam and whether they can trust their banks' web sites.

But if we care about the future of the internet we must take an interest in what authority should be exercised by the International Telecommunications Union or the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers or some other yet-to-be-defined. In fact, we are right on top of a key moment in that developmental history: from December 3 to 14, the ITU is convening the World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT, pronounced "wicket"). The big subject for discussion: how and whether to revise the 1988 International Telecommunications Regulations.

Plans for WCIT have been proceeding for years. In May, civil society groups concerned with civil liberties and human rights signed a letter to ITU secretary-general Hamadeoun Touré asking the ITU to open the process to more stakeholders. In June, a couple of frustrated academics changed the game by setting up WCITLeaks asking anyone who had copies of the proposals being submitted to the ITU to send copies. Scrutiny of those proposals showed the variety and breadth of some countries' desires for regulation. On November 7, the ITU's secretary-general, Hamadoun Touré, wrote an op-ed for Wired arguing that nothing would be passed except by consensus.

On Monday, he got a sort of answer from the International Trade Union Congress secretary, Sharan Burrow who, together with former ICANN head Paul Twomey, and, by video link, internet pioneer Vint Cerf , launched the Stop the Net Grab campaign. The future of the internet, they argued, is too important to too many stakeholders to leave decisions about its future up to governments bargaining in secret. The ITU, in its response, argued that Greenpeace and the ITUC have their facts wrong; after the two sides met, the ITUC reiterated its desire for some proposals to be taken off the table.

But stop and think. Opposition to the ITU is coming from Greenpeace and the ITUC?

"This is a watershed," said Twomey. "We have a completely new set of players, nothing to do with money or defending the technology. They're not priests discussing their protocols. We have a new set of experienced international political warriors saying, 'We're interested'."

Explained Burrow, "How on earth is it possible to give the workers of Bahrain or Ghana the solidarity of strategic action if governments decide unions are trouble and limit access to the Internet? We must have legislative political rights and freedoms - and that's not the work of the ITU, if it requires legislation at all."

At heart for all these years, the debate remains the same: who controls the internet? And does governing the internet mean regulating who pays whom or controlling what behaviour is allowed? As Vint Cerf said, conflating those two is confusing content and infrastructure.

Twomey concluded, "[Certain political forces around the world] see the ITU as the place to have this discussion because it's not structured to be (nor will they let it be) fully multi-stakeholder. They have taken the opportunity of this review to bring up these desires. We should turn the question around: where is the right place to discuss this and who should be involved?"

In the journey from Postel to governance, this is the second watershed. The first step change came in 1996-1997, when it was becoming obvious that governing the internet - which at the time primarily meant managing the allocation of domain names and numbered internet addresses (under the aegis of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority) - was too complex and too significant a job for one man, no matter how respected and trusted. The Internet Society and IANA formed the Internet Ad-Hoc Committee, which, in a published memorandum, outlined its new strategy. And all hell broke loose.

Long-term, the really significant change was that until that moment no one had much objected to either the decisions the internet pioneers and engineers made or their right to make them. After some pushback, in the end the committee was disbanded and the plan scrapped, and instead a new agreement was hammered out, creating ICANN. But the lesson had been learned: there were now more people who saw themselves as internet stakeholders than just the engineers who had created it, and they all wanted representation at the table.

In the years since, the make-up of the groups demanding to be heard has remained pretty stable, as Twomey said: engineers and technologists; representatives of civil society groups, usually working in some aspect of human rights, usually civil liberties, such as EFF, ORG, CDT, and Public Knowledge, all of whom signed the May letter. So yes, for labour unions and Greenpeace to decide that internet freedoms are too fundamental to what they do to not participate in the decision-making about its future, is a watershed.

"We will be active as long as it takes," Burrow said Monday.

Wendy M. Grossman’s web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series.

Image: CC-AT-NC-SA 2.0 Anton Power

Universal digitisation – the infrastructure is there, it’s just being dismantled

Ian Clark talks about universal digitisation and concludes that we should use the current library system and the internet as complementary components to reduce the digital divide.

Those of you who read my blog and follow me online know that two things that really annoy me are the belief that everyone has the internet and therefore we no longer need libraries, and that simply providing access to the internet is enough to ensure an informed populace. Of course, the reality is far more complex than the media and politicians often present. Providing access to the internet is part of the battle (see all my posts here), but the development of skills is also a key component to reducing the digital divide.

At the back end of last week, a report commissioned by Go ON UK revealed that around 16 million people in the UK lack basic online skills (the full report is available here - pdf). Titled “This Is for Everyone” The Case for Universal Digitisation, the report makes the following claims:

There are 10.8 million people in the U.K. who do not use the Internet, and they are consequently more vulnerable. As Booz & Company shows, this is no longer something we can dismiss as somebody else’s problem. We gain the full benefits ourselves only if everyone is online. The lack of basic digital skills for millions means “digitisation” is unbalanced—we will increasingly fall short of the U.K.’s potential if we do not start to address the problem.

…

A 79 percent usage figure means that about one-fifth of the population—including 10.8 million people 15 and older—do not use the Internet at all. In addition, the e-Learning Foundation estimates that 800,000 of the most disadvantaged schoolchildren in the U.K. lack home access to the Internet. [A] BBC study found that of non-users, 71 percent are categorised among the three lowest socioeconomic groups, 51 percent are older than 65, and 50 percent have no formal qualifications.

…

Using the Internet requires only the most basic digital literacy, yet lack of skills is cited as a key reason many people are not online. Indeed, 63 percent of working-age non-users and 78 percent of retired non-users state they do not know how to use the Internet.

Nowhere in the report, however, is there any mention of the key role libraries (or librarians for that matter) can play in enabling “universal digitisation”. And yet, the provision of internet access in the local public library is the only way many can get connected and take advantage of the full range of services available online. Libraries provide (in most cases) free access, skilled support and can often provide a certain degree of ‘training’ for those who simply do not have the skills or confidence to navigate the internet. They are, therefore, crucial in encouraging people online and moving the country towards universal digitisation.

A little while ago I wrote a post explaining what I think needs to be done to address the digital divide in the UK. One of the key points I made is that public libraries should play a key role in getting people connected and enabling the economic benefits that the above report claims will come with universal digitisation. The basic infrastructure already exists to reach the goals outlined in the report, unfortunately local authorities are dismantling it and the national government is standing by and letting it happen.

Ian Clark tweets at @ijclark and blogs at infoism.co.uk/blog

Image: CC BY-NC-SA Eric Hackathorn

Feature Interview: Stephanie de Vanssay on Social Media and Schools

Teacher and web 2.0 advocate, Stephanie de Vanssay has agreed to give an interview for ORGZine.She talks about her projects:integrating the web into the French education system and raising awareness on the benefits of the web 2.0 for children's learning process.

Professor Stephanie de Vanssay, e.l@b vice president and active member of the teachers’ union in France, has been campaigning to integrate the internet into the French school system. She answered questions to ORGZine editor, Tamara Kinja Nyakabasa, and elaborated on her projects, objectives and challenges.

Kinja: If you had to describe in a few words what “Ecole de demain” (School of tomorrow) is all about, what would you say?

“Ecole de demain” is a blog that is trying to provide a platform for debate and reflexion for what our union, the SE-Unsa, wishes in terms of a better and more efficient school of tomorrow. In this context, new technologies have their place with students so that they can utilise them, but also so that new technologies can help them be more active in their learning process.

Added to that, I campaign for an association, e.l@b (Laboratoire. Education. Numerique), which encourages building relations between schools and the digital society in order to educate citizens of the 21st century.

Kinja: What motivated you to engage in this cause?

I’ve worked several years with students in difficulty and I observed that posting on the internet, gathering comments and exchanging with real readers is at the same time accessible, motivating, demanding and very educating. It would be a real pity not to use it.

Kinja: What are the obstacles you have encountered to this day?

There are a lot of obstacles, but contrary to what most people think, they are more of a societal nature than technical. In France, schools are ill equipped, but we most of all have mentalities to change. A lot of teachers and parents think that the internet is mostly dangerous, that screens are bad and all of this doesn’t have its place in the school environment…

Kinja: What do you do to overcome these obstacles?

There is a lot of explanatory work to do: explaining the positive aspects the internet can bring, convincing that using it is a learning process and that it’s by using it at school under the supervision of professors in a teaching environment that children will be able to use it properly, and will learn to avoid certain dangers.

Kinja: Why in your opinion it is important to integrate the web 2.0/social networking sites in the actual education system?

We have to prepare our students to tomorrow’s world. We have to teach them to learn, to understand these tools, to know their possibilities and also their limits…

Just like you won’t overnight let a child cross the road by himself, he needs to be with someone in the web 2.0 and social networking platforms. The school can’t let all this responsibility fall on the families and has to play its part. Especially since we know that the gap today between the wealthy and less fortunate is more and more existent in terms of usage and in terms of equipment. Therefore, if our School wants to be democratic, it has to work on that level as well.

Kinja: Your introductory report makes reference to Twittclasses for student as young as in pre-school. Could you tell us more about it?

I think that if supervised by a vigilant teacher, even young children can make their first steps on social media and ask themselves what can be posted on it or not. Of course, we are talking about a class account controlled by the teacher. Furthermore, the bond created between what happens in class and parents is very interesting. Other teachers prefer creating a class blog to achieve this bond between the school and the family, who also encourages students to relate what they do in class.

Kinja: How do you think students benefit from the integration of Twitter in their day-to-day school activities?

Twitter allows writing short texts (so accessible to all) in a real objective of communication and with access to the outside world. Students, having real interlocutors, are then more attentive with their grammar and spelling so that they can be understood clearly. Some classes use Twitter to share their short stories, to conduct projects by questioning experts, to exchange riddles and enigmas between classes, to play chess or even to exchange geometrical construction programs…

There are several possible projects, and all of them demand a lot reading, writing and comprehension. Added to that, there is also the possibility to educate students about social media by asking them to question what can be posted, the reliability of some information, contacts they can accept or not…

Kinja: What do you say to parents and/or official authorities that worry about this new educating tool; concerning children security (on the web), their focus in class or the place of the teacher in this new system?

It’s all about trusting the teacher, often parents are reassured as soon as the teacher has explained to them the project with its pedagogic objectives of educating about the media. When it comes to official authorities, it is sometimes more difficult with eventual problems or unawareness. We then have to write very serious proposals drawing a lot on past experiences and on official texts, which recommend working with the Technology of Information and Communication for Education (TICE).

It has to be said that it is not about classes where student are on the computer screen all the time (we are far from that), messages are written on paper first after some discussion, especially in primary school classes. There are no reasons for students to be less attentive in class; on the contrary they are more active. Concerning teachers, their role has evolved; they are no longer THE absolute holder of all knowledge, they are more like mediators between accessible knowledge and students. The teacher accompanies in the search, the questioning and the validation by letting children experience.

Kinja: What would be your advice to teachers who wish to start using social media in their classes?

Simply to discuss and exchange with colleagues who are already doing it. It is easy to find them on the web, their experience is crucial to define a project and mutual help and reflexion are very present on social networking sites and blogs.

Kinja: Is there anything you’d like to add?

To conclude, I would say that introducing web2 to schools is an excellent way to approach the challenge of renewing the education system by integrating a degree of uncertainty as recommended Edgar Morin.

Learn more about Stephanie de Vanssay's work and objectives on her Twitter, blog, and union blog.

Image: CC BC-NC ToGa Wanderings

The Billion-Dollar Spree

Wendy Grossman analyses the 2012 US presidential candidates spending. She explains the rules and regulations behind the campaigns funding sources and concludes that in US elections, money is a key factor.

"This will be the grossest money election we've seen since Nixon,"Lawrence Lessig predicted earlier this year. And the numbers are indeed staggering.

Never mind the 1%. In October, Lessig estimated that 42 per cent of the money spent so far in the 2012 election cycle had come from just 47 Americans - the .000015 per cent. At this rate, politicians - congressional as well as presidential – are perpetual candidates; fundraising leaves no time to do anything else. By comparison, the total UK expenditure by all candidates in the last general election (PDF) was £31 million - call it $50 million. A mere snip.

Some examples. CNN totals up $506,417,910 spent on advertising in just the eight "battleground" states - since April 10, 2012. Funds raised - again since April 10, 2012 - $1,021,265,691, much of it from states not in the battleground category - like New York, Texas, and California. In October, the National Record predicted that Obama's would be the first billion-dollar campaign.

The immediate source of these particular discontents is the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that held that restricting political expenditure on "electioneering communications" by organizations contravened the First Amendment's provisions on freedom of expression. This is a perfectly valid argument if you accept the idea that organizations - corporations, trade unions, and so on - are people who should not be checked from spending their money to buy themselves airtime in which to speak freely.

An earlier rule retained in Citizens United was that donors to so-called Super PACs (that is, political action committees that can spend unlimited amounts on political advertising as long as their efforts are independent of those of the campaigns) must be identified. That's not much of a consolation: just like money laundering in other contexts, if you want to buy yourself a piece of a president and don't want to be identified, you donate to a non-profit advocacy group and they'll spend or donate it for you and you can remain anonymous, at least to the wider public outside the Super PAC..

And they worry about anonymous trolling on the internet.

CNN cites Public Citizen as the source of the news that 60 per cent of PACS spend their funds on promoting a single candidate, and that often these are set up and run by families, close associates, or friends of the politicians they support. US News has a handy list of the top 12 donors willing to be identified. Their interests vary; it's not like they're all ganging up on the rest of us with a clear congruence of policy desires; similarly, Super PACs cover causes I like as well as causes I don't. And even if they didn't, it's not the kind of straightforward corruption where there is an obvious chain where you can say, money here, policy there.

If securing yourself access to put your views is your game, donating huge sums of money to a single candidate or party traditionally you want to donate to both sides, so that no matter who gets into office they'll listen to you. It's equally not a straightforward equation of more money here, victory there, although it's true: Obama outcompeted Romney on the money front, perhaps because so many Democrats were so afraid he wouldn't be able to keep up. But, as Lessig has commented, even if the direct corrupt link is not there, the situation breeds distrust, doubt, and alienation in voters' minds.

The Washington Post argues that the big explosion of money this time is at least partly due to the one cause most rich people can agree on: tax policy. Some big decisions - the fiscal cliff - lie ahead in the next few months, as tax cuts implemented during the Bush (II) administration automatically expire. When those cuts were passed, the Republicans must have expected the prospect would push the electorate to vote them back in. Oops.

Some more details. Rootstrikers, the activist group Lessig founded to return the balance of power in American politics to the people, has a series of graphics intended to illustrate the sources of money behind super PACs; the president; and their backers. The Sunlight Foundation has an assessment of donors' return on investment

An even better one comes from the Federal Election Commission via Radio Boston, showing the distribution of contributions. The pattern is perfectly clear: the serious money is coming from the richer, more populated, more urbanized states. The way this can distort policy is also perfectly clear.

One of the big concerns in this election was that measures enacted in the name of combating voter fraud (almost non-existent) would block would-be voters from being able to cast ballots. Instead, it seems that Obama was more successful in getting out the vote.

The conundrum I'd like answered is this. Money is clearly a key factor in US elections - it can't get you elected, but the lack of it can certainly keep you out of office. It's clearly much less so elsewhere. So, if the mechanism by which distorted special-interest policies get adopted in the US is money, then what's the mechanism in other countries? I'd really like to know.

Wendy M. Grossman’s web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series.

Image: CC BY-SA Gaelx

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.