Looking back ORGzine in January: What did you miss?

As well as being the start of a new year, January was my first month editing ORGzine. I’ve learnt a lot and I’m looking forward to bringing you the best discussions of digital rights in February. If you missed anything in the last month, here's a round-up to help you catch up!

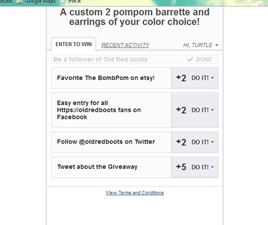

January 1st was Public Domain Day, when work which has come out of copyright that year is released into the public domain. We marked this day somewhat belatedly at the end of the month with a pair of articles, one an explanation of why the public domain is shrinking and changes to copyright law, accompanied by some amazing graphics. We also questioned the assumption that terrible things happen when work enters the public domain.

We remembered the sad passing of internet activist Aaron Swartz in an obituary, which discusses the injustices he was subject to.

We marked International Data Privacy day with an article about anonymity and privacy, and an anonymously written article about the quest to retain privacy within the blogging sphere.

Also this month was a discussion of whether censoring “pirate” sites works. The author of the research in question will be talking about his findings in more detail in February’s ORgzine. Another article looked at the five next big challenges for internet activism. We also looked at the future of government’s priorities for broadband. We also looked at the recent censorship of Google in China, and how the internet is censored in the rest of the world.

Wendy M Grossman enlightened us on a range of issues this month, from attempts to download apps to her new phone anonymously, the relationship between free internet content and advertising, why some online technologies soar and others fail, and most recently about the absurdity of the US law which makes unlocking a phone illegal.

Looking forward: In February’s ORGzine:

This month we’ll be looking at whether ad-blocking is the next legal battleground, and whether traditional news has been replaced by the many opinions of social media. One of the authors of ‘Clickonomics’ discusses the implications of his research, and facial recognition in the private and public spheres is explored.

If you have anything you want to add, please feel free to comment on the articles, you may get an answer from the author!

If you’d like to write for us, or have an idea about what you’d like to read about, then we’d love to hear from you. Email Danya at orgzine.editor@openrightsgroup.org

Pwned

"The professional who can't quickly get at your credit card database moves on just as quickly to someone more easily attackable. The elite attacker who wants you, just you, and nobody else but you…is going to keep at it until he gets you." Wendy M Grossman looks at what we can learn from the cyber-attack on the New York Times.

There's no question that the story of the complex and persistent four-month attack by (probably) Chinese hackers on the IT systems at the New York Times is one of the best few stories of its genre since Clifford Stoll invented it with his 1989 book The Cuckoo's Egg. It's not just the fact of the attack, but the detailed and excellent reporting of it (by Nicole Perlroth). Most companies decline to tell the world what happened to them. The Times behaved like a good newspaper should, and acted in the public interest. Later, the Wall Street Journal confirmed that it, too, had seen its systems infiltrated. In both cases, the goal seems to have been to monitor the papers' coverage of China.

The result is that now we know a lot more about the inner workings of modern attacks on computer systems: highly motivated, layered, multi-faceted, stealthy, patient, persistent. As Charles Arthur outlines over at the Guardian, the hacking scene (with apologies to old-timers, using "hacking" to mean breaking into computers rather than inventing things that do what you want) these days is in layers, each with its own characteristics. Arthur calls them amateurs (in which category he includes Anonymous); commercial hackers (those who steal credit card details for financial gain); and government and military hackers. In tennis terms, amateurs are club players, commercial hackers are paid folks - coaches, trainers, racquet stringers, promoters, agents - and government and military hackers are the elite athletes of the top 100. Somewhere there's a Roger Federer of computer cracking that all the other guys wish they were as good as.

It's striking that, as the Times relates, in 2011 the US Chamber of Commerce thought it had shut down a breach, only to find months later that an internet-connected thermostat and printer were still chatting away with computers in China. This prospect was, if you recall, the real point of the escapades that Columbia University's Ang Cui and Sal Stolfo showed off that same year. It was scary and dramatic that they could embed malware in documents to make printers smoke, if not burst into actual flames. But their main point was that any internet-connected device, even one using unique firmware its manufacturer believes is safely obscure, can be turned into a secret surveillance device. Things like printers and routers are especially effective listening posts, since they are necessarily open to everything on their network, and even a thin trickle of data is enough to send out bank account numbers - or user IDs and passwords for later use.

Think of that next time some manufacturer responds to a researcher demonstrating a new attack by saying that it's too far-fetched or something only an obsessive genius would think of. Nothing is too far-fetched if it can be shown to work, and "the other side" can afford to buy plenty of obsessive geniuses.

The story also has done a lot to highlight the limits of our ability to defend ourselves. It's no surprise, for example, that Symantec's anti-malware offerings failed to spot the attackers, and not just because the attacks used zero-day exploits that by definition have yet to appear in the wild. F-Secure's outspoken Mikko Hypponen was quite clear about this last June, when, he wrote bluntly in an opinion piece for Wired, "Consumer-grade antivirus products can’t protect against targeted malware created by well-resourced nation-states with bulging budgets". The occasion was the discovery of the Flame malware and his admission that his company (and its competitors) had samples dating to 2010 (and even earlier); their automated reporting systems had simply never flagged them as something to investigate. The key points are that no system is 100 percent perfect (at least, if you want also to be able to do actual work on that computer), and that of course well-funded attackers test their malware, before deployment, against all of the leading anti-malware software to ensure it will get through. "We were out of our league," Hypponen concludes.

It is of course a cue for another round of stories asking yet again whether anti-virus software is over. I wrote one of these myself, in 2007. The answer is obviously no, and not just because, as vendors will tell you, anti-virus software has been evolving right alongside the malware it's intended to detect. Even if it hadn't you'd still need it to block all the same old stupid stuff that's been circulating for years.

The Times story also shows us how many more kinds of motivated attackers you may have than you think. The paper has simultaneously to protect its systems from defacement or disruption by amateurs; its database of customer credit cards and personal details from professional commercial hackers; and its reporters and their systems from targeted attacks by the elites employed by states and (perhaps soon) other very large organisations that seek to control what it says about them. Each of those groups has a different MO and also - and this is key - a different amount of patience. The amateur who wants to embarrass you will give up when his skills run out. The professional who can't quickly get at your credit card database moves on just as quickly to someone more easily attackable. The elite attacker who wants you, just you, and nobody else but you…is going to keep at it until he gets you.

Wendy M. Grossman’s web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Image: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Flickr: Dale

Do bad things happen when works enter the Public Domain?

New research shows that the traditional arguments for copyright extension are as flawed as we always suspected. Theodora Middleton explores the terrible things which are meant to happen when work enters the Public Domain.

Copyright is generally defended in terms of the stimulus it gives to creative production: what motivation would anyone have to do anything ever if they don’t get decades of ownership afterwards? But then how do you justify the continual increase in copyright terms which has taken place over the last century, and applies retrospectively to works made in the past? Extending their copyright protection can’t stimulate their production – they’ve already been made!

Three main arguments are advanced: that works which fall into the public domain will be under-exploited, because there will be no incentive to produce new works; that they will be over-exploited, with too many people using them and therefore reducing their worth; and that they will be tarnished, by being reproduced in low quality ways or associated with undesirable things.

All three arguments, it seems, are nonsense. A new research paper, “Do Bad Things Happen When Works Enter the Public Domain?:Empirical Tests of Copyright Term Extension”, has taken the example of audiobook reproductions of public domain and copyrighted works, and investigated the three potential types of damage that are thought to occur in the transition to public domain status:

Our data suggest that the three principal arguments in favor of copyright term extension—under-exploitation, over-exploitation, and tarnishment—are unsupported There seems little reason to fear that once works fall into the public domain, their value will be substantially reduced based on the amount or manner in which they are used. We do not claim that there are no costs to movement into the public domain, but, on the opposite side of the ledger, there are considerable benefits to users of open access to public domain works. We suspect that these benefits dramatically outweigh the costs.

Our data provide almost no support for the arguments made by proponents of copyright term extension that once works fall into the public domain they will be produced in poor quality versions that will undermine their cultural or economic value. Our data indicate no statistically significant difference, for example, between the listeners’ judgments of the quality of professional audiobook readers of copyrighted and public domain texts.

It’s getting to be that time again, when Mickey Mouse gets closer and closer to the public domain — and you know what that means: a debate about copyright term extension. As you know, whenever Mickey is getting close to the public domain, Congress swoops in, at the behest of Disney, and extends copyright.

The results are clear. The so-called “harm” of works falling into the public domain does not appear to exist. Works are still offered (in fact, they’re more available to the public, which we’re told is what copyright is supposed to do), there are still quality works offered, and the works are not overly exploited. So what argument is there left to extend copyright?

This article was reprinted by kind permission of the Open Knowledge Foundation. Follow the links to read more blog posts by Theodora Middleton and learn more about the Open Knowledge Foundation.

Image: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Leo Reynolds

Blog giveaways used to be simple

Blogger OrigamiGirl looks at 'giveaway' conventions in the fashion blogging world and how entering these competitions has moved from being a way of connecting with other bloggers, to a streamlined process involving handing over a worrying and ever increasing amount of personal data.

Origami Girl blogs about fashion, feminism and children's toys at origamigirlheroics.blogspot.com

Before I begin this rant (and be warned, it really is a rant), I will concede something: my blog isn’t all that private.

There are some who share their blogs with the wider internet, but keep its existence secret from their intimate friends. There are some who share their writings only with their friends in a private blog, and the rest of the world does not get a peek.

I do not go to great lengths to keep my blog secret from any group, it is out there if you have heard of my full name and give me a google. In reverse, if you only know my blog title, my full name is out there without too much searching. Indeed it terrifies me how easy it is for my whole world to be exposed by Google. Despite this ease of discovery I still use of pseudonym when blogging. However, this act of creating a layer of privacy is not about demanding, or needing, total anonymity. For me it is simply about not wanting to conflate my personal and professional life. My blog-writing and my work-writing should be under separate names.

You know what is ruining that? You know what is ruining my happy blog space?

Giveaways.

Let me explain. A giveaway is a phenemon common to the fashion-blogger circle I frequent. It is the term used for when a blogger is given an offer by a company of a free object to pass on to her followers in return for some advertising. For example, a fashion blogger offers a dress for free to her followers who must fulfil some criteria for a chance to win said dress. The dress company gets promotion to the hundreds who read her blog and trust her recommendations. The hundreds of followers are given a gamble for free clothes.

I have been reading and commenting on blogs for a long time and I have seen my community of fashion bloggers become fully integrated into many companies marketing strategies. I’m going to talk you through the three operating systems in the history of giveaways and how this process of trying to win the unobtainable dress has turned into a privacy nightmare and left me abandoning a number of blogs.

Stage 1

The follower friendly way. In the ‘historic’ way of operating a giveaway the blogger put up some photos of the dress you could win and a link to the dress-shop. The requirements to enter were that her followers leave a comment and their choice of how to be contacted if they win. Her followers are perhaps enthralled with the dress and go buy it anyway when they don’t win.

It is likely that you have to be a follower to enter the competition, but she trusts you to follow in the way you choose, and so gains a few fans who hadn’t been swayed to subscriptions before, or who were searching for giveaways because they love free things. It’s a win-win all round.

Stage 2

The Facebook way. This is where the blogger and the dress-shop have become obsessed with Facebook. To enter a giveaway now you have to: follow the blog AND ‘like’ the blog on Facebook AND ‘like’ the dress-shop on Facebook as well. Perhaps you also have to follow the blog on Bloglovin so they can have the pleasure of counting their followers in a whole new way. After the giveaway is over you find yourself with a Facebook feed clogged with updates for blogs that you already follow and a stream of pictures of models posing in clothes you can't afford. All I want on Facebook are my friends, not a cluster of adverts.

Stage 3

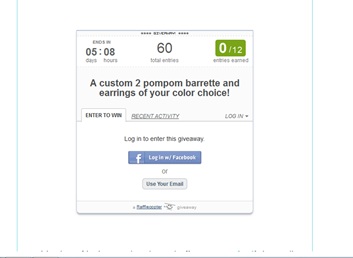

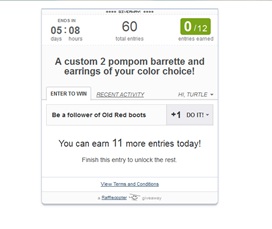

The Rafflecopter - complete meltdown. This is where it lately all went a little bit mental.

Someone has decided that giveaways now need to be done through a third party mediator. Now, not only do you allow the dress-shop, Facebook and the blog running the giveaway access to your name, email address and buying habits, a third party has streamlined the entire process.

This is the app you have to use to enter a lot of giveaways now. Note the link to Facebook immediately highlighted.

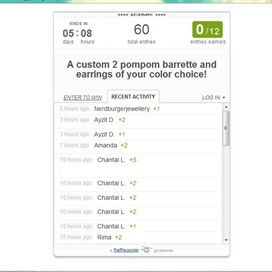

I can just click on ‘recent activity’ and can see who entered!

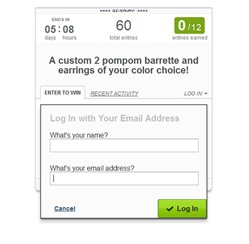

Oh look. I either sign in with Facebook or give this company my email address.

I entered with a fake name and the email I use for junk stuff to get to the next page. It asks me to finish this entry to unlock the rest? Oh wait, I haven’t done enough? Apparently I need to follow this blog. I already do follow her via Blogger. But that isn’t enough, it wants Bloglovin as well.

Like the Cat in the Hat the Rafflecopter says, ‘Oh no, that is not all I can do’. For more chances to win a random thing, I have further options to give away even more of my privacy. Eleven more entries which, note the language, I can earn. I can login to my Etsy account, Pinterest, Twitter. Putting all those separate identities into one zone. The attitude is that the default is to have no wish for identity diaspora, despite the fact that many bloggers use a pseudonym.

At no point is the giveway framed as thanking supporters for following your blog, for comforting you in hard times and giving you endless compliments. Now you have to earn your right to have a chance for a free thing.

When I see a mess of privacy invasion like this, crossing my Facebook, Google account, Bloglovin and other social networks over without giving me any guarantee as to what they will do with my information, I do not want to enter your giveaway. Sadly, it makes me angry with the blogger. It’s highly likely that the bloggers using this app don’t understand the implications. However, those of you who ask for me to follow you in multiple ways should at least consider that too much of anything becomes an irritant.

You don’t even have to do it this way. One of the blogs I love is still doing blog giveaways in what I deem a respectable way. I would like to quote what she says in her giveaway:

“You don't even have to be a follower of my blog. You don't have to like this or follow that... This isn't about self promotion. It's about saying thank you. You can be a first time visitor or someone who has visited my blog since it started three years ago...You can be from half way across the world, my home town, my life here at Kent...anyone is welcome to enter.”

Because honestly, I want to spend more time on her blog and appreciate her more because she asks so much less. So please! Stop using Rafflecopter! Let’s make giveaways about community and thanking followers again, rather than about giving our lives to Facebook.

The Incredible Shrinking Public Domain

The public domain — the wellspring of material that everyone is free to use and build upon — has been steadily shrinking, as the Centre for the Study of the Public Domain in North Carolina tells us.

Our economy, culture and technology depend on a delicate balance between that which is, and is not, protected by exclusive intellectual property rights. Both the incentives provided by intellectual property and the freedom provided by the public domain are crucial to the balance. But most contemporary attention has gone to the realm of the protected. The Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke Law School is the first university center in the world devoted to the other side of the picture. its mission is to promote research and scholarship on the contributions of the public domain to speech, culture, science and innovation, to promote debate about the balance needed in our intellectual property system and to translate academic research into public policy solutions.

Public Domain Day is January 1st of every year. If you live in Europe, January 1st 2013 would be the day when the works of painter Grant Wood, anthropologist Franz Boas, writer Robert Musil, and hundreds of others emerge into the public domain – where they are freely available for anyone to use, republish, translate or transform. In the EU, citizens can now freely copy, share, or incorporate thousands of works into digital archives. They can make versions of “European Gothic,” incorporating Wood’s art. They can do all of this and more, without asking permission or violating the law.

What is entering the public domain in the United States? Nothing. Once again, we will have nothing to celebrate this January 1st. Not a single published work is entering the public domain this year. Or next year. In fact, in the United States, no publication will enter the public domain until 2019. Even more shockingly, the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that Congress can take back works from the public domain. Could Shakespeare, Plato, or Mozart be pulled back into copyright? The Supreme Court gave no reason to think that they could not be. And wherever in the world you live, you will likely have to wait a very long time for anything to reach the public domain.

When the first copyright law was written in the United States, copyright lasted 14 years, renewable for another 14 years if the author wished. Jefferson or Madison could look at the books written by their contemporaries and confidently expect them to be in the public domain within a decade or two. Before 1978, the copyright term was still 28 years from the date of publication, renewable once for another 28 years — but 85% of copyrights were not renewed and went immediately into the public domain. Under the 1976 Copyright Act, which went into effect in 1978, the term became 50 years from the date of the author’s death (with no need to renew to have the full term).

When the first copyright law was written in the United States, copyright lasted 14 years, renewable for another 14 years if the author wished. Jefferson or Madison could look at the books written by their contemporaries and confidently expect them to be in the public domain within a decade or two. Before 1978, the copyright term was still 28 years from the date of publication, renewable once for another 28 years — but 85% of copyrights were not renewed and went immediately into the public domain. Under the 1976 Copyright Act, which went into effect in 1978, the term became 50 years from the date of the author’s death (with no need to renew to have the full term).

In 1998, the copyright term was increased to 70 years after the death of the author, and to 95 years after publication for corporate “works-for-hire”, locking up an entire generation of works for an additional 20 years. With these and interim extensions, the copyright term has been extended eleven times in the past fifty years. This extension — which increased the copyright term to life plus 70 years and 95 years for corporate authors — was not only granted to future works. It was retroactively applied to works that had already been created and enjoyed their full copyright term, and were set to enter the public domain. None of these works will enter the public domain until 2019. The already diminished public domain has been frozen in time.

an additional 20 years. With these and interim extensions, the copyright term has been extended eleven times in the past fifty years. This extension — which increased the copyright term to life plus 70 years and 95 years for corporate authors — was not only granted to future works. It was retroactively applied to works that had already been created and enjoyed their full copyright term, and were set to enter the public domain. None of these works will enter the public domain until 2019. The already diminished public domain has been frozen in time.

Now? In the United States, as in most of the world, copyright lasts for the author’s lifetime, plus another seventy years. And we’ve changed the law so that every creative work is automatically copyrighted, even if the author does nothing. We have little reason to celebrate on Public Domain Day because our public domain has been shrinking, not growing.

In 2003, many of those who rely on the public domain had their hopes dashed by Eldred v. Ashcroft, the case that upheld the 20-year extension to the copyright term. The Constitution declares that copyrights must only be “for limited times” and that Congress can only create exclusive rights to “promote the progress” of knowledge and creativity.

Despite those limitations, in Eldred, the Supreme Court held that Congress could retrospectively lengthen copyright terms – something that seemed neither “limited” nor aimed at promoting progress. (It is hard to incentivise dead authors!)

But 2012 was to hold in store an even more grievous blow to the public domain. In Golan v. Holder, the Supreme Court held that Congress can remove works from the public domain without violating the Constitution and create a new legal monopoly over it. What’s more, the Court declared, Congress can do so even when it is clear that the new right “does not encourage anyone to produce a single new work”!

2.jpeg)

This decision marked a significant departure from the “bedrock principle” that once works enter the public domain, they remain there, free for anyone to use and build upon. Golan was different from Eldred because while the works in Eldred were on the brink of entering the public domain, the works at issue in Golan were already in the public domain, and conductors, educators, film archivists and others were legally using them.

In upholding the law, the Golan majority explicitly endorsed the position that the public has no rights to the public domain. None. Under US law as declared by the Court in this case, copyright is now officially “asymmetric”. While those who have copyrights enjoy vested, legally protected rights, those who enjoy works in the public domain acquired ownership of them. The majority could not seem to imagine that the public had rights other than “ownership” over a free, collective culture.

What are the limits on this decision? Could Congress recall the works of Shakespeare, Plato and Mozart from the public domain, and create new legalised monopolies over them? It is hard to imagine anything more contrary to the First Amendment – would privatising Shakespeare by government decree abridge freedom of speech? – or to the attitudes of those who penned the Copyright Clause that limits Congress’s power to create new exclusive rights. Yet if one reads Golan, one searches in vain for any limiting principle on Congress’s actions. In this decision, Justice Ginsburg’s majority opinion effectively denies the public domain any meaningful Constitutional protection. Under the US Constitution, says this case, the public domain is “public” only by sufferance. It may be privatised at any moment, at the whim of the Congress and without violating the Bill of Rights.

In our opinion as legal scholars, this decision is shockingly cavalier in its dismissal of the importance of the public domain to free speech and to the progress of science and culture. It is also, again in our opinion, unsupported by the text, structure and history of the Constitution. Indeed, it seems flatly contrary to the dictates of the First Amendment and the limitations imposed by the Copyright Clause. Yet its message, however lamentable, is clear. If the public domain is to be protected in the United States, it is not going to be through the Constitution, but through reasoned argument, democratic pressure and legislative action. The public domain will be “public” only so long as the public demands it.

In the United States, as in most of the world, copyright lasts for the author’s lifetime, plus another seventy years. Let’s assume for the sake of illustration that on average, an author creates a work at age forty and lives until age seventy, making the “life” part of the copyright term thirty years from the date of creation. Using this assumption, these extensions of the copyright term can be depicted in the following manner. Each extension represents a winnowing of the public domain.

In addition to extending the copyright term, recent laws eliminated the requirement that authors “opt in” to copyright protection by affixing a basic copyright notice — the word “copyright” or © with a name and year next to it. This change took effect in 1989, and copyright now adheres the moment a work is fixed, whether or not the author wants to protect or sell the work, with no easy way to "opt out" — think of all the amateur videos, travel photos, blog postings, witty musings, jam sessions, or useful tidbits that people want to freely share and don’t intend to commercialize.  Estimates are that under the opt-in system perhaps only 10% of works included a copyright notice; the remaining 90% went immediately into the public domain. Compare that to today, when 100% of works automatically have life plus 70 years or 95 years of protection and are off limits to artists, educators, archivists, remixers, scholars, and everyone else who might want to freely use them. As a result, the chart above only shows part of the story — the shrinking of the public domain has been exponential.

Estimates are that under the opt-in system perhaps only 10% of works included a copyright notice; the remaining 90% went immediately into the public domain. Compare that to today, when 100% of works automatically have life plus 70 years or 95 years of protection and are off limits to artists, educators, archivists, remixers, scholars, and everyone else who might want to freely use them. As a result, the chart above only shows part of the story — the shrinking of the public domain has been exponential.

The exceptionally long copyright term has also created a growing limbo of “orphan works.” These works are still presumably under copyright (only works published before 1923 are conclusively in the public domain), but they are commercially unavailable and the copyright owner cannot be found (tracking down the copyright holders of older works is often impossible — read accounts of thwarted efforts to do so here). Orphan works comprise much of the record of 20th century culture — studies have found that only 2 percent of works between 55 and 75 years old continue to retain commercial value. For the other 98% of works, no one benefits from continued copyright protection, while the entire public loses the ability to adapt, transform, preserve, digitise, republish, and otherwise make new and valuable uses of these forgotten works. Read more about the current costs associated with orphan works here and here.

The exceptionally long copyright term has also created a growing limbo of “orphan works.” These works are still presumably under copyright (only works published before 1923 are conclusively in the public domain), but they are commercially unavailable and the copyright owner cannot be found (tracking down the copyright holders of older works is often impossible — read accounts of thwarted efforts to do so here). Orphan works comprise much of the record of 20th century culture — studies have found that only 2 percent of works between 55 and 75 years old continue to retain commercial value. For the other 98% of works, no one benefits from continued copyright protection, while the entire public loses the ability to adapt, transform, preserve, digitise, republish, and otherwise make new and valuable uses of these forgotten works. Read more about the current costs associated with orphan works here and here.

This steady erosion of the public domain is happening just as the internet and digital technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to find, share, catalog, preserve, and remix its riches — foreclosing its enormous potential to feed creativity, innovation, democratic participation, and knowledge advancement.

This steady erosion of the public domain is happening just as the internet and digital technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to find, share, catalog, preserve, and remix its riches — foreclosing its enormous potential to feed creativity, innovation, democratic participation, and knowledge advancement.

In recent years, the public domain has been diminished in many ways. Most relevant to Public Domain Day are the changes described above, but other expansions of intellectual property law have also contracted the public domain. These include changes in the subject matter covered by intellectual property (for example, patent protection has been extended to gene sequences and common business methods) and in the activities regulated (for example, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act backs technical controls that curtail personal, non-commercial, and traditionally “fair” uses of digital content).

To learn more about these developments, see Professor James Boyle’s The Public Domain, available for free online here. This content was republished by kind permission of the Centre for the Study of the Public Domain.

Lock Box

In the US, unlocking your mobile without the permission of your mobile operator has become illegal. Wendy M Grossman discusses why this ridiculous law is against consumers' interests.

I have to confess, I'm fascinated by the news that unlocking a cell phone under contract without the permission of your carrier became illegal in the US on Saturday January 26, 2013. Partly, I find the story astonishing because it's such a minute thing to have outlawed. But partly, because it shows how far out of step the US continues to be in the mobile phone world - and just how twisted some laws can get.

It isn't unreasonable for the companies that sell people mobile phones at subsidised prices to lock them into contracts whose ultimate purpose is to ensure that the subsidy is repaid over time. If you don't like that setup, there's a simple solution, assuming you can afford it: buy your own phone at full price. It ain't cheap, to be sure, to buy something new and fancy like a Samsung Galaxy Note 2. For that phone, the best price I could find before Christmas: £419, shipped direct, customs fees and delivery paid, from Hong Kong, it seems to be somewhat higher now. But buying the same phone, subsidiesd, from a carrier meant being required to sign up for a pricey monthly data plan instead of the inexpensive but more-than-adequate one I already had. If you did the math, buying the phone outright at the outset would pay for itself in less than the two years the contract would have been in force - in 17 months, to be precise. Maybe that makes sense if you change your phone every 18 months to two years, but much of the significant benefit to a new phone going forward will be in the software updates - and you can have those anyway.

But not necessarily in the US, where any European resident would conclude the consumer protection forces have failed utterly in the mobile market for some decades now. Even though the US has migrated to standards used in the rest of the world, it's still often not as easy as it should be to find a setup where you can stick your service's SIM card into any phone you happen to have handy - or insert any SIM card that makes roaming cheaper into the phone you have. It's amazing there hasn't been a class action suit about this. (Side note: that article seems to confuse unlocking the phone with jailbreaking it. They're not the same.)

If you've read the stories you, like me, might be wondering what on earth the Librarian of Congress - a job title that sounds like the owner ought to be utterly harmless - is doing banning unlocked cell phones. Shouldn't that be a job for the Federal Communications Commission or the Federal Trade Commission? People who deal with communications and consumer protection?

If the law at issue were contract law and the terms to which people agree when they buy their subsidised cell phones, that would be true. Instead, it turns out that the law being invoked is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (1998), which bans "circumventing" technology designed to protect copyright. Back when the DMCA was being negotiated, folks like the Electronic Frontier Foundation (and many others) warned that it would have far-reaching effects. People talked about a legal ban on liquid paper (which you could use to white out a copyright notice), scissors (which you could use to cut one off), and (of course) crypto.

It's safe to say that no one, certainly not the framers of the law, saw it as a measure that would ultimately be used to protect the market control of a few large phone companies at the expense of millions of ordinary Americans. The EFF has been on the case all this time, however, and in the rule-making process last November, asked the Librarian to grant an exemption for cell phones. The even weirder upshot of this whole thing is that the Librarian granted in 2009 and renewed in 2012 an exemption for *jailbreaking* phones (but not tablets or video game consoles on the basis that they're too hard to define). This week, EFF argued in a statement quoted by many media that locking phone users into a phone carrier is not at all what the DMCA was meant to do.

The Librarian's argument seems to be that it's not fair use to break the lock because you don't own the software - which has led commenters on AndroidAuthority to suggest taking a copy of the phone's built-in software and then flash the phone with unlocked custom software, a notion that might be within the spirit of the law but sounds like it violates the letter. On the other hand, it's a ridiculous law clearly against consumers' best interests.

It's easy for the rest of the world to laugh and say, oh, well, that's American cellular telephony for you. But the DMCA was followed by anti-circumvention laws in the EU and elsewhere. They're unlikely to be abused in the peculiar way that will take hold in the US this weekend. But there will always be people and companies looking for ways to twist the law to serve their particular purposes. A case like that provides a great demonstration of just why laws need to be drafted as narrowly and precisely as possible. And why there's so much danger in bad law that sticks.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

The Right to Anonymity is a Matter of Privacy

January 28th is International Privacy Day. As the first of a series of articles about privacy, Jillian C York from the Electronic Frontier Foundation talks about how she sees anonymity as being a matter of privacy.

Jillian C. York is EFF's Director for International Freedom of Expression. She specializes in free speech issues in the Arab world, and is also particularly interested the effects of corporate intermediaries on freedom of expression and anonymity, as well as the disruptive power of global online activism.

Throughout history, there have been a number of reasons why individuals have taken to writing or producing art under a pseudonym. In the 18th century, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay took on the pseudonym Publius to publish The Federalist Papers. In 19th century England, pseudonyms allowed women - like the Brontë sisters, who initially published under Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell - to be taken seriously as writers.

Today, pseudonyms continue to serve a range of individuals, and for a variety of reasons. At the Electronic Frontier Foundation, we view anonymity as both a matter of free speech and privacy, but in light of International Privacy Day, January 28, this piece will focus mainly on the latter, looking at the ways in which the right to anonymity - or pseudonymity - is truly a matter of privacy.

Privacy from employers

Human beings are complex creatures with multiple interests. As such, many professionals use pseudonyms online to keep their employment separate from their personal life. One example of this is the Guardian columnist GrrlScientist who, upon discovering her Google+ account had been deleted for violating their “common name” policy, penned a piece explaining her need for privacy. Another example is prominent Moroccan blogger Hisham Khribchi, who has explained his use of a pseudonym, stating:

When I first started blogging I wanted my identity to remain secret because I didn’t want my online activity to interfere with my professional life. I wanted to keep both as separate as possible. I also wanted to use a fake name because I wrote about politics and I was critical of my own government. A pseudonym would shield me and my family from personal attacks. I wanted to have a comfortable space to express myself freely without having to worry about the police when I visit my family back in Morocco.

Though Khribchi’s reasoning is two-fold, his primary concern - even stronger than his need for protection from his government - was keeping his online life separate from his employment.

Even Wael Ghonim - the now-famous Egyptian who helped launch a revolution - conducted his activism under a pseudonym...not to protect himself from the Egyptian government, but rather because he was an employee of Google and wanted to maintain an air of neutrality.

Privacy from the political scene

In 2008, an Alaskan blogger known as “Alaska Muckraker” (or AKM) rose to fame for her vocal criticism of fellow Alaskan and then-McCain-running-mate Sarah Palin. Later, after inveighing against a rude email sent to constituents by Alaska State Representative Mike Doogan, AKM was outed - by Doogan - who wrote that his “own theory about the public process is you can say what you want, as long as you are willing to stand behind it using your real name.”

AKM, a blogger decidedly committing an act of journalism, could have had any number of reasons to remain anonymous. As she later wrote:

I might be a state employee. I might not want my children to get grief at school. I might be fleeing from an ex-partner who was abusive and would rather he not know where I am. My family might not want to talk to me anymore. I might alienate my best friend. Maybe I don't feel like having a brick thrown through my window. My spouse might work for the Palin administration. Maybe I'd just rather people not know where I live or where I work. Or none of those things may be true. None of my readers, nor Mike Doogan had any idea what my personal circumstances might be.

Though Doogan claimed that AKM gave up her right to anonymity when her blog began influencing public policy, he’s wrong. In the United States, the right to anonymity is protected by the First Amendment and must remain so, to ensure both the free expression and privacy rights of citizens.

Similarly, in 2009, Ed Whelans, a former official with the Department of Justice, outed anonymous blogger John Blevins - a professor at the South Texas College of Law - in the National Review, calling him “irresponsible”, and a “coward.” Blevins took the fall gracefully, later explaining why he had chosen to blog under a pseudonym. Like Khribchi, Blevins’ reasons were numerous: he feared losing tenure and legal clients, but he also feared putting the jobs of family members in the political space at risk.

Privacy from the public eye

A friend of mine - let’s call him Joe - is the sibling of a famous celebrity. But while he’s very proud of his sibling, Joe learned early on that not everyone has his best interests at heart. Therefore, Joe devised a pseudonym to use online in order to protect the privacy of himself and his family.

In Joe’s case, the threat is very real: celebrities are regularly stalked, their houses broken into. His pseudonym keeps him feeling “normal” in his online interactions, while simultaneously protecting his sibling and the rest of his family from invasions of privacy.

Achieving anonymity online

Anonymity and pseudonymity may seem increasingly difficult to achieve online. Not only do companies like Facebook restrict your right to use a pseudonym, but even when you do think you're anonymous, you might not be - as blogger Rosemary Port found out in 2009 after Google turned over her name in response to a court order.

While we should continue to fight for our privacy under the law, the best thing we can do as users to who value our right to anonymity is to use tools like Tor. Anonymous bloggers can use Global Voices Advocacy's online guide to blogging anonymously with WordPress and Tor. And all Internet users should educate themselves about what is - and isn't - private on their online accounts and profiles.

Read more articles by Jillian C York and find more out about the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Jillian can be followed on Twitter at @jilliancyork and you can read her blog here.

Censorship cat and mouse

Google makes a fuss about Chinese censorship, but has always complied with other government's requests to remove content.

Google has withdrawn a feature which alerted Chinese users when they searched for a censored term. Previously this would cause them to be temporarily disconnected from Google’s services. A message appeared, stating that searching for this term (eg. “freedom”, but also intriguingly, “triangle”) could cut off your connection, and clarified that this was out of the search engine’s control. The tool was implemented by Google in May 2012 and made censorship more transparent to Chinese web users, as they could identify search terms which were flagged. I had the pleasure of stumbling across the list of banned search terms while researching this article.

Google has often been vocal in its opposition to censorship, and the alert tool showed they did not condone China’s “Great Firewall”. The government retaliated by blocking the feature, and Google responded by finding a way to bypass this. This game of cat and mouse continued until Google decided to embed the feature into its start page, meaning the Chinese authorities either had to block Google altogether or tolerate the alert feature.

All was well until In December 2011, when following weeks of aggressive blocking of Google’s services by the Chinese government, Google removed the offending feature. Google stated “Chinese officials consider censorship demands to be state secrets, so we cannot disclose any information about content removal requests.” Wired speculated that Google removed the feature to make the service more user friendly since it: “keeps getting them booted off the internet.” But this explanation makes no sense since the alert feature stopped them being disconnected if they searched for forbidden terms.

It is more feasible that Google complied to retain their corporate presence in the country, regardless of the amount of frustration it may cause internet users. Despite being criticised for being too accommodating to Chinese censorship, Google has good reason to keep on the right side the government. Even though a small percentage of Chinese people use Google as their default search engine, the vastness of the population means this is still a large number of people. Google has huge potential for growth in China and their shareholders know it. Google also has to consider revenue from both global companies advertise in China, and Chinese companies who advertise globally. This seems to be a more convincing reason for Google’s acceptance of China’s terms. For however much Google’s actions could characterise it as a protector of free speech, it’s primary motivation as a business will always be profit.

Worldwide 40 countries censor the internet in some way and Google states that some of its products are blocked in 25 of the 100 countries that it operates in. Most of us expect widespread censorship from authoritarian governments. What about the places which most consider to be the most free and open societies? In the US, Google censors search results to comply with legal complaints about the infringement of copyright. Since 2011, Google's auto-complete feature censors words connected with file-sharing, such as “bittorrent”, and swear words, (although it does not censor either from search results). Google’s image search also censors explicit content as a result of having removed a ‘no filtering’ option from the search options.

Google makes public the number of requests it receives to remove internet content (as well as the number of requests for individuals’ private data). These included US law enforcement agencies’ appeals for the removal videos from YouTube containing evidence of police brutality. Google refused to remove the offending videos, but did comply with 75% of all removal requests in the same six month period. The number of requests to remove information by US officials to Google more than doubled in the second half of 2011. “Figures revealed for the first time show that the US [government] demanded private information about more than 11,000 Google users between January and June [2011] almost equal to the number of requests made by 25 other developed countries, including the UK and Russia.” Google complied or partially complied with 90% of these requests in the same six month period.

The censorship in China exists to stop the spread of what the Chinese Communist Party would describe as dissenting views which they believe would damage the fabric of society. Parallels can be drawn between this and US law enforcement’s desire to remove images of police brutality from the internet. The reasons for wanting to remove the content seem to be similar, but the difference is in the extent of the censorship. While censorship may happen in “western democracies”, it is not as pervasive as in China.

Google does comply with some requests to remove content from the UK and US governments. These still involve value judgements about what should and should not be seen, what is deemed improper, or what we should be shielded from. It is this judgement, combined with an air of infallibility, that makes censorship so dangerous. Who is making decisions about what we can and can’t see, and why should we trust their judgement over ours?

You can test websites to see if they're censored in China at this website. Danya is a Communications and New Media Intern at the Open Rights Group.

The Superfast and the Furious

The internet is central to modern life, and next-generation fixed and mobile broadband are vitally important for the economy. But the case for spending any more taxpayers' money to subsidise very fast connectivity is weak, argues Sarah Fink.

Sarah Fink is a Digital Government Research Fellow at the Policy Exchange. She is the co-author of a report which argues that politicians have become overly focused on broadband speeds.

In our recent Policy Exchange report - “The Superfast and the furious: Priorities for the future of UK broadband policy” – we are broadly supportive of the steps the government is taking to drive out fibre optic networks to the majority of the population, to accelerate the roll out of 4G wireless networks, and to deliver on a universal service commitment for broadband.

However, our research found that there are significant gaps in digital capability, for both consumers and small businesses. This may be preventing them from making the best decisions and getting the maximum benefit from internet connectivity, irrespective of the speed of their connection.

To inform our research and understand general attitudes towards connectivity, we conducted polling with Ipsos Mori of around 2000 consumers and 500 small and medium enterprises. We found that four in five people think the internet is something that everyone should be able to get access to, and two thirds of people think it is more important for everyone to have access to a basic broadband service than it is to boost top speeds in select parts of the country.

But we also found that only around one in five people is confident estimating how much data their household uses in a typical month (and this figure falls to fewer than one in ten for the over-65s), and only around a third of people are confident they can choose the best broadband package for their household’s needs (again falling to below one in five for the over-65s). Consumers need to be more confident in their interactions with broadband providers in order for competition to work effectively.

Our research also showed that the majority of small businesses are relatively conservative when it comes to adopting new technology. We found that about half of people think that most businesses should be ready to take bookings or orders online – but only about a third of small business report that they have the capability to manage online transactions. This is particularly concerning for policymakers as we know that small businesses that embrace the internet grow substantially faster than their offline peers.

This suggests that the focus for digital engagement needs to extend to cover capability for small businesses. In the UK 16 million people lack basic online skills, 4.5 million of these are in the UK workforce. Improved levels of internet capability and engagement will ensure that people are realising for themselves the best economic and social outcomes from connectivity.

In addition to basic capability, consumers also need to have enough information to help them make good decisions. In other markets, including energy and financial services, there are moves to ensure consumers have access to personalised data about their usage so that they can compare products and shop around. Many internet service providers and mobile network operators already provide this sort of information for their customers, but where this isn’t already happening, it should be encouraged.

Although we think that industry is generally best placed to articulate the benefits of broadband and to drive consumer engagement, there is still an important role for government. For most people, the prospect of engaging with the government may not be the most compelling reason to get online. Indeed, in research previously published by Policy Exchange, we found that for older people the primary attraction of getting online was highly personal, and included motivation such as communicating with dispersed family or seeing photographs of loved ones.

But government needs to be prepared to push ahead with the digital-by-default agenda. In particular, government should drive forward delivery where it will be accessible by most people, even if some people will not be able to benefit (either because good broadband infrastructure is absent or because they are not confident going online). There is a risk that innovative services are held up indefinitely to avoid delivering a service that fails on universal accessibility. And for those who do remain offline, digitisation may still have important ancillary benefits. By innovating and driving the majority of interactions online, efficiency savings can be unlocked and used to enhance the offline service for the (decreasing) number of people who are not able to access online content.

Getting the core infrastructure in place will be important for future competition and innovation, and will be necessary to support mainstream take up. But when it comes to any further spending in this arena, however, we think policymakers need to reflect carefully before allocating any more funding to large subsidies for superfast infrastructure. Instead the government should focus on helping the 10.8 million people not online - half of whom are over 65 - and do more to help small businesses make the most of the opportunities presented by the internet.

You can learn more about the Policy Exchange and follow them on Twitter at @PXDigitalGov and Sarah at @SarahFinkPX.

A Year After SOPA, A Look At The Next Five Battles For Internet Freedom

A year since the largest protest in internet history against the Stop Online Privacy Act (SOPA) what are the most important issues that activists to focus on?

Trevor Timm is an activist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. He specialises in surveillance, free speech, and government transparency issues. He is also the co-founder and executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which supports and funds independent journalism organisations dedicated to transparency and accountability in government.

A year ago today, internet users of all ages, races, and political stripes participated in the largest protest in internet history, flooding USA Congress with millions of emails and phone calls to demand they drop the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) — a dangerous bill that would have allowed corporations and the govenrment to censor larger parts of the Web.

But the price of freedom is eternal vigilance, and the fight for internet freedom continues. Here’s a look at the top five issues SOPA activists should focus on next:

Stop the Trans-Pacific Partnership: After the historic collapse of SOPA, the content industry has claimed it wants to shy away from anymore excessive legislation that could potentially censor the internet. Instead, it has turned its attention to the international stage. The Trans-Pacific Partnership, better known as TPP, is the latest multilateral trade agreement carrying abusive copyright provisions that the United States, on behalf of Hollywood and major copyright-holding interests, is forcing onto citizens of other countries.

Unfortunately, the treaty is being negotiated in complete secrecy and with no democratic oversight, so we don't even know exactly what these countries have been debating. Fortunately, drafts of the agreement have leaked, and it's at least clear TPP would force countries to drastically lengthen their copyright terms, restrict fair use, institute digital locks to keep people from sharing information, and place greater burdens on websites hosting content. You can read a detailed explanation here. This infographic shows how TPP will affect countries around the world.

If you're reading this from the USA, please go to our action center to tell your representative in Congress to demand transparency surrounding TPP negotiations.

Demand Patent Reform: Recently, our broken patent system has proven to be one of the biggest threats to innovation online. Big tech companies have been locked in billion dollar legal patent wars that do nothing for the consumer. Last year, Google and Apple spent more on patent suits than they did research and development. Meanwhile, untold numbers of patent lawsuits (and even mere threats of suits) involve patent trolls, those who sue start-ups for vague patents that can destroy their business before it gets started.

Luckily, people are starting to notice. Noted Appeals Court Judge Richard Posner called the patent system “chaos“ and said there are too many patents in America, as he dismissed a prominent case involving Apple and Motorola. The Saving High-Tech Innovators from Egregious Legal Disputes (SHIELD) Act, written by Representative Peter DeFazio, along with co-sponsor Representative Jason Chaffetz, would help put an end to a lot of the problems we’ve been noting for years now. Tell your congressional representative to support real patent reform so the tech industry can thrive.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) has set up a webpage called defendinnovation.org where we lay out possible reforms for the patent system. You can leave you own comment about how the patent system has affected you and sign our petition, which we plan on taking to Congress along with a list of reforms.

Reforming Draconian Computer Crime Law: The internet has been in mourning this week as one of its true innovators and pioneers, Aaron Swartz, took his own life at the age 26. He was, of course, an early developer of the RSS specification, Creative Commons, Reddit, and a multitude of other projects. Notably, the SOPA protests likely would not have happened without him. He founded Demand Progress, one of the groups which organized the blackout.

At the time of his death, Aaron was facing a relentless and unjust prosecution under the outdated and draconian Computer Fraud and Abuse Act for the supposed “crime” using Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) computer network to download millions of academic articles from the online archive JSTOR, allegedly without "authorization." For that, he faced 13 felony counts, which carried the possibility of decades in prison and crippling fines. His case would have gone to trial in April.

EFF, along with a multitude of other groups, have taken a bill written by Representative Zoe Lofgren and written the first draft of what we hope will become known as “Aaron’s Law” — which will go a long ways in preventing a similar situation from happening to a freedom fighter like Aaron again. If you live in the US you can take action and email your members of Congress to tell them to support reform of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act here.

Stop the new Internet Surveillance Law: There are rumours that the Obama Administration will propose a far-reaching new internet surveillance law, dramatically expanding the the Communications Assistance to Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), which forces forcing telephone companies to build a wiretap-friendly backdoors into all their technology — but not social networks and other web-based communications services.

The White House and the FBI have not released what is in the proposed legislation, but one report states the FBI wants to require internet companies, like Google, Facebook, and Twitter to build the same type of backdoors for real-time government surveillance. This not only poses a threat to privacy, but internet security and innovation as well. We need to tell Congress this is unacceptable before it's too late.

Protect Cell Phone Location Data: Cell phone location data is some of the most sensitive data one can possibly send out. Your cell phone sends a signal back to cell phone towers every seven seconds; that data, mapped out over days or weeks, can show "an intimate portrait of a person’s familial and professional associations, political and religious beliefs, even health status," as the New York Times put it.

The US government made a staggering 1.3 million requests for that sort of data last year — and the government believes they can get it without a warrant. The GPS Act, a bill introduced by Senator Ron Wyden would force law enforcement to get a warrant for this data, just like the Fourth Amendment should require.

Meanwhile, app developers have also been sucking up users' location information, many times without the user being aware of that collection. It paints just as intimate a picture of people’s lives as government tracking does. To that end, Senator Al Franken has introduced a bill to restrict and regulate the practice so users are better informed and protected when giving this type of information to private companies. In addition, EFF has also written a Mobile Privacy Bill of Rights, serving as a best practices guide that developers should follow when writing applications for cell phones.

Read more articles by Trevor Timm and find more out about the Electronic Frontier Foundation. He can be found on Twitter at @TrevorTimm, and he co-operates the @Drones Twitter account, which reports on surveillance drones in the US and the secrecy surrounding military drones around the world.

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.