Digital Colonialism: Africa's new communication dimension

Milena Popova examines the new challenges facing Africa that come with modernisation and technological expansion.

Milena is an economics & politics graduate, an IT manager, and a campaigner for digital rights, electoral reform and women's rights.

Africa is rapidly becoming "the place to be" for Western businesses. Despite common preconceptions expressed in Twitter hashtags like #FirstWorldProblems, a lot of African economies are growing rapidly, and US and European companies are looking to the continent for their next wave of consumers. This is not as surprising as you might initially think. Compared to Western Europe with its declining birth rates and, in many countries, negative population growth, Africa's population continues to grow rapidly. Nigeria alone has more babies than all of Western Europe put together, while life expectancy across the continent is increasing. The population of Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to rise by nearly 40% to over 1 billion by 2025. Real GDP growth for Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to be around the 4.5-5% mark for the rest of the decade. While this is not quite the double-digit growth of the Asian Tigers in the 1990s, it's a rate that countries like the UK can only dream of right now.

Technology plays a key part in Africa's growth. Some time this quarter, mobile phone penetration on the continent is projected to exceed 80%, and with Airtel having just successfully completed a 4G/LTE trial I wouldn't be surprised if Nigeria soon had better 4G coverage than the UK. Mobile banking is far more successful in Africa than it has been in many Western countries. Mobile phones are even used in pilot projects to improve cervical screening in Tanzania. In a high-population, rapid-growth setting with advanced technological capability and infrastructure, it should come as no surprise then that intellectual property is also rapidly becoming a hot topic in the region. The African Union proposal for a Pan-African Intellectual Property Organisation (PAIPO) started gathering momentum in the final three months of last year, raising a lot of concerns in the process. The objectives of the proposed organisation as listed in the draft statute include among other things:

- Ensure the effective use of the intellectual property system as a tool for economic, cultural, social and technological development of the continent;

- Promote the harmonisation of intellectual property systems of its Member States, with particular regard to protection, exploitation, commercialisation and enforcement of intellectual property rights;

- Initiate activities that strengthen the human, financial and technical capacity of Member States to maximise the benefits of the intellectual property system to improve public health and eradicate the scourge of piracy and counterfeits on the continent; and

- To foster and undertake positive efforts designed to raise awareness on intellectual property in Africa and to encourage the creation of a knowledge-based and innovative society as well as the importance of creative industries including, in particular, cultural and artistic industries.

A tall order if I ever saw one, and many commentators in and outside Africa are rightly questioning whether the copyright maximalism that clearly underlies these proposals is the right way to achieve any of these goals. There is a nagging suspicion that this initiative is driven not so much by a concern for the interests of people in Africa as by a desire of Western corporations to have an intellectual property regime which suits their ambitions for the continent. Given that only around 10% of applications for the registration of intellectual property (IP) rights in Africa are made by African citizens or residents, that suspicion does seem justified. Whatever intellectual property regime the African Union settles on will have a profound impact on the whole continent and its people.

As well digital technology, IP regulations have implications for food security, access to affordable medicine, as well as access to knowledge and educational resources - all areas deeply relevant to Africa's social and economic development. The PAIPO draft statute has been criticised for lacking subtlety and nuance, advocating a "one size fits all" approach to intellectual property. The calls for harmonisation of African IP laws are a definite cause for concern. If intellectual property is to be viewed as a tool for development rather than an end in itself imposed from outside, it is clear that a differentiation of IP regimes is appropriate between countries as diverse as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Libya, South Africa or South Sudan.

There is also a lack of clarity on the proposed new body's relationship with existing African IP organisations, as well as with African efforts within the wider WIPO framework. Arguably, scarce resources would be wasted on creating a third African IP body for the convenience of Western businesses and would be much better spent in encouraging the emergence of local creative and knowledge economies. The public discourse around the PAIPO proposals resulted in a petition ahead of the 5th African Union Conference of Ministers of Science and Technology in Brazzaville, Congo, in November last year, calling for an urgent rethink around IP frameworks in Africa. As Dr. Caroline Ncube, IP scholar at the University of Cape Town, points out, the outcome of this meeting is unclear, but it is likely that for now at least the current draft statute is on ice. Will it come back in a different form? Probably. Let's hope that when it does, at least some of the key issues and concerns have been addressed.

Milena tweets as @elmyra.

Why do copyright monopolists think they can just steal other people's work?

"Copyright monopolists claim a continued kind of ownership even after something is sold." They insist on the idea of controlling the fruits of other people’s labour, such as when other people copy a particular file. This attitude is offensive, insulting, and antithetical to a free market. Rick Valkfinge tells us why.

The famous philosopher John Locke once published the idea that a person has the right to profit off of the fruits of their labour. This is only partially true: once you have sold something, you hold no further rights to profit off of it. This is fairly obvious, but needs to be stated for context.

An entrepreneur can sell one or both of two things: you can sell products, and you can sell services. If somebody decides to make shiny things and sell them, they have a right to profit off the fruit of that labour – but only up until the point where they sell the shiny things. Their ownership of the shiny thing, and their right to profit, ends the second the item is sold to somebody. Conversely, if somebody decides to sell their time in selling services, their right to profit ends the second they stop working for the person they have sold their time to.

In geek terms, entrepreneurship is finding a value differential in society, constructing a conduit between the two endpoints and sticking a generator in the middle of the conduit. Profit ensues from the generator until the value differential has equalised to the point where the pressure is no longer sufficient to overcome the resistance of the generator, at which point the conduit stops working.

This is how a free market works, and it is regarded as the foundation of our economy. However, copyright monopolists are trying their hardest to muddle this simple and fundamental principle, by claiming a continued kind of ownership even after something is sold. That’s not how a market works. That’s a monopoly. That’s harmful. That’sbad.

We have indeed observed before how the copyright monopoly stands in direct opposition to property rights, sabotaging this foundation of our economy and the fundamentals of entrepreneurship.

So for the sake of argument, let’s assume I am given a copy of the movie The Avengers by somebody. It is one of many copies. There are many ones like it, but this one is mine. It is my property in all its aspects.

However, copyright monopolists would argue that they should continue to control my property. This is not just strange, but offensive. Even worse, when I do some labour on my own property, such as executing a “copy file” command on it, the copyright monopolists claim they should control that labour too – as well as the fruits of it. This is outrageous and has me fuming over their arrogance.

When I manufacture another copy of the Avengers using my own property and my own labor, copyright monopolists somehow believe they have a right to the fruits of my labour. I find that idea offensive and insulting.

It is true that the ease of my labour depends on many people having worked on other things before me. However, this is true with all entrepreneurship. My ability to copy a particular file depends not just on those who created the file, but also on those who invented electricity generators, the modern graphics card, the keyboard, wire insulation, storage media, networking protocols, and many, many other things. This is as ancient as Rome: entrepreneurship has always built on the already-performed work of others, and one set of previous such entrepreneurs do obviously not get any kind of special privileges on a functioning market.

Anybody is free to create shiny things, but their ownership over the shiny thing stops the instant they sell it. That’s how a market works. Claiming control over the fruits of other people’s labour, such as when somebody makes a copy of a file using their own property, is deeply, deeply immoral.

This piece was previously published on TorrentFreak. You can read more articles by Rick Falkfinge and others on his website.

Clickonomics: The use of Mediafire, Megaupload, Filesonic, Hotfile, Rapidgator, Rapidshare...

In January Ernesto talked about whether current “anti-piracy” measures were effective. A look at the subject in more detail from Tobias Lauinger, who tells us about his recent research.

Tobias Lauinger is a PhD student in the Systems Security Lab at Northeastern University, Boston. In the past two years, his research has focussed on illicit activities in the One-Click File Hosting ecosystem.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA) already allows copyright owners to have infringing files taken down from hosting services and search engines. The Stop Online Privacy Act (SOPA) law proposal would have introduced a similar take-down scheme directed against entire web sites. But do these methods really work?

One-Click Hosters (OCHs) are web-based file hosting services. Users can upload potentially large files and obtain a unique download link in return. While OCHs such as Mediafire, Megaupload, Filesonic, Hotfile, Rapidgator, Rapidshare and several hundred others have various legitimate use cases, they are also frequently used to distribute copyrighted works without permission (“piracy”). In fact, download links for infringing files hosted on OCHs can be found on a wide range of blogs, discussion boards and other web sites, so-called indexing sites.

In the US, laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and the proposed – but later abandoned – Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) aim at combatting online piracy. Critics of these laws point to their potential for abuse as a danger to freedom of speech and question whether these laws effectively fulfil their purpose.

Measuring the visibility and effectiveness of current anti-piracy methods was the goal of our recent research. In a nutshell, we extracted download links to infringing content from 10 small and large indexing sites, and we checked for how long these files remained available on the respective OCH. We found that most infringing files remained available for rather long time periods: our data even suggests that only a surprisingly small fraction of the files were deleted due to DMCA takedown notices. The DMCA, or the way in which copyright owners were using it, was apparently not enough to render infringing content unavailable.

Analysing uploader behaviour and the structure of a few larger indexing sites, we found that there is no single indispensable actor in the OCH ecosystem. Uploaders of infringing content move to another OCH when the anti-piracy efforts of their current OCH become too restrictive. Furthermore, even shutting down a large OCH (such as Megaupload) tends to have little effect on the availability of infringing content because indexing sites often use many OCHs in parallel.

In conclusion, current anti-piracy efforts are visible, but they fail to make infringing content unavailable. So what about future anti-piracy measures? SOPA contained a takedown notice scheme to prevent “foreign US-directed sites dedicated to the theft of US property” from receiving funds or user traffic from US-based advertisement networks, payment processors and ISPs. Paradoxically, we would expect SOPA's anti-piracy tools to be most effective against OCHs, even though OCHs are probably not as problematic as most indexing sites from a legal point of view.

A recent development in this context is increased pressure from payment processors such as Paypal. In fact, most OCHs cannot accept payments through Paypal any more due to a change in Paypal's policies. If other payment processors follow the same strategy as Paypal, OCHs may be forced to intensify their own anti-piracy measures in order to maintain their capability of accepting credit card payments. The interesting observation is that this strategy closely resembles the ideas behind SOPA, but it could be realised even without SOPA's controversial takedown regime.

The current approach of economic pressure on payment processors may lead to a less profit-driven piracy ecosystem. However, it is difficult to envision that legal measures could make piracy disappear entirely in a free society. It is more likely that users will continue to have the choice between piracy and legitimate offers. Anti-piracy laws on the one hand, and the attractiveness (and availability) of legitimate offers on the other hand, will shape the mainstream user behaviour in the future. Certain levels of piracy will remain, but how much of an economic problem they represent is an entirely different question.

The full study is available online: Tobias Lauinger, Martin Szydlowski, Kaan Onarlioglu, Gilbert Wondracek, Engin Kirda, and Christopher Kruegel: Clickonomics: Determining the Effect of Anti-Piracy Measures for One-Click Hosting. It will be pesented at the 20th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS 2013) in San Diego, CA on 26 February 2013.

Merchants of Chaos

"If people realised they were joining a belief system involving billion-year-old space aliens they would never sign up." Scientology bans its followers from reading critics' views. Wendy M Grossman discusses Scientology's relationship with the internet.

Somehow, I managed to miss the exploding tomato.

I think I understand it, though: there is a state of mind you get into when you have been battered relentlessly with unerring but false logic: if this, then this, then this other thing, then the next thing, and you see…you must admit this, and that means you were wrong all along. The floor slides away from you the way it does in the description Mrs Morton gave Berton Roueche of her bouts of labyrinthitis, a disease of the inner ear, and if you are not left alone the only way you can reassert the world as you know it is to bellow out the facts as you know them.

When you read the BBC Panorama journalist John Sweeney's new book about his time investigating Scientology for two Panorama episodes, one in 2007 and the other in 2010, The Church of Fear, you get the sense that this was his state of mind when he turned into - his term - the exploding tomato. This becomes clearer when you're shown the steps that led him there. Sweeney has apologised for his loss of control many times. Last night, speaking in East Grinstead, the town where Scientology has its UK headquarters, he gave us a small re-enactment. Up close, that was LOUD.

In an interview yesterday with The Register, Sweeney references a line I had forgotten, said to me in 1994 by former Scientologist Robert Vaughan Young to explain why he was glad he did not have to face the internet during his time as a national spokesman for the Church of Scientology: "It's going to be to Scientology what Vietnam was to the US."

Eighteen years later, it seems clear he was right.

On Sweeney's 2010 Panorama, The Secrets of Scientology, the actor Larry Anderson, explains that his 33 years in Scientology began to end when he decided to break with Church of Scientology (CoS) policy to go online and see what critics said about it. What he found was the secret documents at the heart of the conflict described in my 1995 Wired piece, whose reverberations set the framework for the copyright-related notice and takedown rules still in effect today. These "OT III" materials outline the beliefs you only learn hundreds of thousands of dollars into the practice of Scientology: the story of Xenu.

The OT III - for Operating Thetan, level III - documents escaped total Scientology control when they became an exhibit in Lawrence Wollersheim's 1980 suit against the CoS for damages after leaving the organisation. Then came the internet, which for the first time allowed former and disaffected Scientologists to find each other and share their stories. In 1994, the "Operating Thetan" documents made their appearance on the Usenet newsgroup alt.religion.scientology. When their publication brought legal and law enforcement attacks, copies spread more and more widely. The CoS was about as successful in keeping them offline as the RIAA and MPAA: today, they're not only on Usenet and the web but readily accessible on your favourite torrent site, and there are summaries on Wikipedia, About.com, and, well, everywhere.

In 1994, a former Scientologist called the CoS "bait and switch", arguing that if people realised they were joining a belief system involving billion-year-old space aliens they would never sign up. This was why the alt.religion.scientology dissidents were so intent on getting the "secret scriptures" out in public: break the CoS's rigid control over that information and you break an important element of the recruiting mechanism. In the 1970s, a campus recruiter could invite students to an introductory meeting confident that they would know very little about the organisation. Today's students have found Scientology's history, controversies, and belief system on their phones before he's finished his opening sentence. If China can't entirely insulate its population from the internet, what chance does Scientology have?

They can still try, and some will let them. In the video clip linked above, Sweeney says the CoS told him it discourages members from accessing outside media because they are "merchants of chaos". In his book, he quotes from celebrity interviews given him for his 2007 Panorama, Scientology and Me that he was not allowed to broadcast. (Later, the CoS included excerpts from those same interviews in its crossfire documentary, Panorama Exposed, enabling the BBC to use those bits in 2010.) In Sweeney's account of these interviews, Kirstie Alley describes herself as "a little bit stupid on the internet" and says she doesn't use it; Leah Remini says, "I don't go on the internet".

By this time, Scientology's innermost beliefs are probably better understood and better known by those outside the group than those inside it. Because: until you have reached (at considerable expense) the OT III stage of studying Scientology, the core of Scientology beliefs is not disclosed to you. The reason, Hubbard wrote in 1967, is that exposure to these powerful secrets without proper preparation will send you insane, then kill you. The blank stares of Scientologists you ask about Xenu may simply mean they really don't know yet.

"We'll just run the SPs [Suppressive Persons] right off the system. It will be quite simple," Elaine Siegel, then a member of the Office of Special Affairs International, wrote to Scientologists online in 1994. Famous last words.

Wendy M. Grossman’s web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series

Frictional arithmetic

What do we consider currency? Wendy M Grossman discusses whether cash creates more friction than electronic forms of payment.

"Business models based on friction, as opposed to consumer value-add, will wither and die," Mark Hale, head of payments for KPMG, said at yesterday's Westminster eForum on digital payments. You can see his point: who now has the patience to stand in a long line waiting to pay? Waiting is friction. Answering questions is friction. Online, time-to-delivery is friction, which is why Amazon.com is trying so hard to shrink it.

Is cash friction? That's less clear. There are plenty of people — in the UK, most notably Consult Hyperion's Dave Birch — who will tell you that it is. The British Rail Consortium's policy lead, Richard Braham, on the other hand, pointed out that last year 58 percent of transactions were in cash. "We're more likely heading to the cardless society than the cashless society," he said.

That makes intuitive sense to me: for a quick getaway for small purchases it's hard to beat plunking down exact change. But just as the speed and lower risk of credit cards have abolished paper checks/cheques from in-person transactions, I can see where for many people the speed and convenience of tapping a mobile phone on a reader would kill off the business of carrying plastic credit cards.

We're a long way from there yet, however, and it's as sensible trying to predict the eventual outcome as it is to try to predict which media formats will die. In fact, if the history of media is any guide, most of today's forms of payments will survive in some shape, depending on their cultural context. For most Westerners, with our bank accounts and financial services, digital payments are a luxury, in Kenya they fill such an enormous market gap that M-Pesa has been a huge success and is changing the landscape.

Some support for Braham's position came from Matthew Hudson, the head of business development, fares and ticketing for Transport for London. When it launched Oyster cards in 2003, TfL had no idea it would become the largest contactless card issuer in the UK: 52 million cards issued to date. Oyster is just one step in a series intended to reduce costs. Ticketing started in the 1850s to eliminate the "massive" amounts of fraud involved in accepting cash directly. Recently, London buses began accepting payment via Barclaycard's contactless Wave. By November, anyone with a contactless payment card, native or foreign, will be able to use it throughout TfL's system. Eventually, the system will effectively be back to directly accepting cash - albeit digital cash. What's likely ending is the Ticket Era. But Hudson is, he said bluntly, not remotely interested in mobile phone payments as long as consumers have no idea whom to call when the system fails (although he loves the Barclaycard plastic pay tag you can glue to the back of your phone). "Interoperability means nothing to consumers," he said.

It takes a large-scale operation to appreciate that point: uncertainty and confusion about who is responsible for which failures - do you call the mobile phone manufacturer, the mobile network operator, the handset manufacturer, the operating system vendor, the app publisher, or the company you're buying from? — are the app killers. Especially given today's situation with security; earlier in the week, Trustwave launched its 2013 report, which showed that the average length of time from intrusion to containment is 210 days. In 76 percent of the cases Trustwave investigated, organizations did not know they'd been hacked until an outsider told them — regulators, law enforcement, the public. Mobile phones are already targets for malware; so much more so when they are digital wallets.

Hudson's comments make it clear how fast players and methods are proliferating. It's what you expect from an immature industry: an explosion of experiments and options in which unexpected players emerge, usually followed by a shakeout leaving behind a relatively few large, successful winners. Both the UK and the EU are thinking about this progression. In early February, the UK's Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, talked about opening up payment systems. Last year, the an EU green paper on card, Internet, and mobile payments studied how to remove obstacles and provide effective governance for the new era. The framework for electronic money was created some years back.

Yet things are getting stranger than they may realise. What's a currency? We usually think of the government-backed, state-sponsored variety as the hard stuff. Yet Hudson sees Oyster cards as a "currency" people convert Sterling into. Frequent flyer miles and loyalty points are also obvious currencies, even if what you can buy with them is limited. But what about Amazon gift certificates? On his blog, Birch tells the story of his brief study of payment systems in use among online sex workers. Few take Paypal, which allows chargebacks and freezes accounts unpredictably if it suspects illegal activities. Most customers eschew credit cards as too tightly coupled to their real-world identities. But Amazon gift certificates: set up a new account with a different email address, charge to real credit card. Birch argues it provides a sufficient level of pseudonymity while still giving both sides the ability to trace the other in case of fraud. And it's a whole lot simpler than Bitcoin. In digital payments, complexity is friction.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

ParlTrack

ParlTrack is a website which pulls data from the European Parliament and re-publishes it in an accessible format. Stefan Marsiske tell us about how is creation can be used by campaigners and citizens alike. It has been actively used in the campaigns on ACTA, net neutrality, open government and open data, privacy and copyright.

Stefan is, amongst things, a software developer and a policy geek, who supports various non governmental organisations with his diverse set of skills. Coming from a telecommunications industry background, he engages with innovation, communication, security, privacy, technology, society and freedom. In his spare time, he loves building infrastructure.

The European Parliament is:

A) a bureaucratic political maze

B) incomprehensible

C) a democratic asset

D) all of the above

You've probably chosen D, and you're right. But engaging with political institutions is crucial if we want to:

1. Safeguard an open internet

2. Get access to social security for all Europeans

3. Work towards a humane refugee policy

4. [FILL IN YOUR OWN IDEALISTIC GOAL HERE]

The European Parliament (EP) is known for being an impenetrable institution, despite the fact that it makes decisions that affect citizens’ lives all over the European Union. As its power grows, it is even more important for us to understand how the EP comes to decisions and makes laws. Greater exposure of the European Parliamentary processes can only be a good thing: it will give citizens more understanding of and engagement in politics, and as a result promote greater democratic legitimacy.

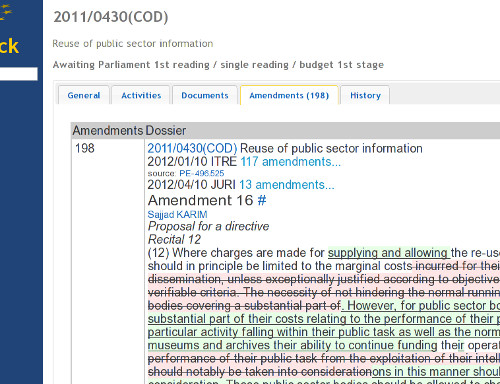

So how could the EP’s processes be revealed? ParlTrack is a website which aims to make the EP more accessible to citizens and campaigning organisations. It publishes information about the EP legislative process which consists of dossiers, information about MEPs, committee agendas and vote results. Whereas previously this information was presented in a format which was difficult to use, (such as pdfs that lacked search functions), ParlTrack re-publishes this information in a more user friendly format. It has been actively used in the campaigns on ACTA, net neutrality, open government and open data, privacy and copyright.

ParlTrack was set up originally by activists in order to gather information during the campaign against the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade-Agreement (ACTA). In the process of collating this information the activists gathered data about the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). This resulted in the production of profiles, which included contact information for the MEPs, which allowed the campaigners to approach the them more efficiently.

European legislation has global consequences. One of the current contentious issues is European data protection, and whether it is setting global standards. International trade agreements like the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade-agreement (ACTA) have wide-reaching effects, not only would it have affected our own lives through more repressive internet policing, but also affect the access of medicines for patients in developing countries.

The result of years of hard work culminated in protests all over Europe against ACTA in 2012. After a leak from Wikileaks, the first volunteers mobilised against ACTA, and the campaigning continued throughout the secretive negotiations. The Lisbon Treaty in 2009 gave the EP new powers over matters to reject international trade agreements. Later when the final text of ACTA was submitted to the EP, campaigning intensified. The strength of Europe's disagreement was shown by a torrent of several thousand protest emails that were sent daily to MEPs.

Whenever something happens at the EU parliament, there is always some kind of administrative procedure attached. Mostly it's one or more committees together producing a report, which is first debated and then voted on. Of course the details are a bit more complex.

So, how can ParlTrack be useful to campaigners? If a group has an interest in what was written in a certain report, they may need to find out, amongst other things, who is responsible for writing it. The campaigners can raise awareness using various media channels such as twitter, phone or email. When a campaigner is contacting an MEP, they need to have an idea who to talk to, and why. Presenting the right arguments to the right person is vital. ParlTrack was developed to help answer these questions.

When the European Commission finally submits a law-proposal to the European Parliament, civil liberties organisations campaign to try to defend the good parts and provide suggestions on how to improve the bad parts of the proposal. Many citizens interested in engaging in the EP’s legislative process volunteer to draft and rate amendments, analyse texts, and use various media channels to campaign for a their desired outcome.

ParlTrack is like a dashboard: campaigners can sign up to receive notification of important dates such as deadlines for the submission of amendments, votes and other events. They can also track dossiers using email and RSS. It is also a useful resource for finding out more information about your representatives.

ParlTrack is like a dashboard: campaigners can sign up to receive notification of important dates such as deadlines for the submission of amendments, votes and other events. They can also track dossiers using email and RSS. It is also a useful resource for finding out more information about your representatives.

ParlTrack’s content is Open Data, so some campaigning organisations such as the Paris-based La Quadrature du Net – who have similar values to the Open Rights Group, take the next step and reuse the data published by ParlTrack to build their own tool. Political Memory tracks the political decisions of the MEPs from a digital rights perspective. This makes the MEPs' views on topics such as software patents, copyright reform, network-neutrality, and privacy completely transparent to anyone with an interest in finding out.

ParlTrack was also useful for the huge noise-making project LobbyPlag, which uses the amendments for the Data-Protection directive from Parltrack and traces them back to the companies that lobbied for them.

Another feature of ParlTrack is the ability to track amendments that an MEP has made. This information was not previously available to the public. Before late 2012, amendments to EU law were buried in sometimes huge PDF documents containing many hundred small snippets of text changes. One recent addition to ParlTrack, which is particularly popular, is the ability to make direct links to particular amendments with hyperlinks. As a result, debate is much simpler: Twitter can be used to send around an important amendment for everyone to see and give their opinion. A related and supposedly fun game - for policy geeks at least – is to select a random MEP and try to guess her or his home country and party.

Another feature of ParlTrack is the ability to track amendments that an MEP has made. This information was not previously available to the public. Before late 2012, amendments to EU law were buried in sometimes huge PDF documents containing many hundred small snippets of text changes. One recent addition to ParlTrack, which is particularly popular, is the ability to make direct links to particular amendments with hyperlinks. As a result, debate is much simpler: Twitter can be used to send around an important amendment for everyone to see and give their opinion. A related and supposedly fun game - for policy geeks at least – is to select a random MEP and try to guess her or his home country and party.

ParlTrack already provides valuable insights, but the current state is barely scratching the surface of what is possible. There are many immediate and mid-term improvements ahead. The most important is probably the web-service, where organisations can maintain their commentary and analysis based on ParlTrack data. Another interesting development could be to highlight trending topics and MEPs that drive the most visitors. Predictions when a dossier should enter the next procedural step could be calculated from historical data. It would be also interesting to follow when and how these directives are implemented in the member-states.

ParlTrack so far has been fully funded by Stefan, which he was luckily able to do so due to some spare resources he had. He is raising funds because he would like spend more time working on ParlTrack. You can donate money on his fundraising page. You can follow ParlTrack on Twitter.

Image: Stefan Marsiske CC-BY-SA

The one true account of the history of news

Has the paper of record has been replaced by the tweet of the moment? Richard Hine looks at how the way we consume news has changed.

Richard Hine began his career as an advertising copywriter. After moving to New York at the age of 24, he held creative and marketing positions at Adweek, Time magazine, where he became publisher of Time’s Latin America edition, and The Wall Street Journal, where he became vice president of marketing and business development.

Once upon a time there was news. Things happened. Smart journalists were assigned to report and write about these events. An all-powerful editor decided how the stories should be assembled and displayed in a way that best indicated their relative importance to the community. And the world, in the form of a newspaper, was delivered directly to your doorstep.

“News” was a real-life storybook with a beginning, middle and an end.

We believed in it.

“News” was the way we, as individuals, could make sense of the world at least once a day.

We agreed this to be true.

Plus, the “news” was mostly good. Suddenly, it was the 1990s! The economy was strong. America was not at war.

We were happy.

And then it was 1996. We all had cable TV. And 20 million of us were waiting patiently for our dial-up internet connection to go through. But “news” was still “news.” Despite the predictions of media experts, CNN hadn’t killed newspapers or even newsmagazines. In fact, when big stuff happened live or was given saturation coverage on CNN, print sales went up—people’s desire to read about what happened, to understand it, to put it into the context of our shared history, actually increased.

Along came a Fox.

Until Fox News launched in 1996, nobody knew how unfair and unbalanced the news was. Thankfully, Fox rectified that. It helped America understand that a blowjob in the White House was the only thing we needed to worry about, despite whatever Osama Bin Laden might have been planning.

By 2000, Fox News was so powerful that when it hired a cousin of George W. Bush and allowed him to award the 2000 Presidential Election to George W. Bush even though the election was still “too close to call” by any traditional journalistic standards, all the other networks went along with the plan. (Later, when traditional journalistic organisations actually counted all the votes, it turned out Al Gore had actually won. But I guess we should just get over it and stop being such sore losers, right?)

1996 also saw the launch of a comedy program called The Daily Show which, in the era of the “fake news” disseminated by Fox News, quickly became one of the most trusted news sources in the world.

You know the rest, right?

Terror attacks. Phony intelligence. Fake wars. Torture. The New York Times goes along with it all. Holy shit, what kind of world is this?

We weren’t happy.

Nothing was true.

We couldn’t trust anyone.

Except maybe bloggers. And citizen journalists. And social media. And suddenly, now, what’s in the newspapers and on the TV doesn’t actually matter anymore. The only thing that matters is the news we choose to read and share and tweet and joke about. And our Klout scores.

Your mind is being polluted. Unless you agree with me.

When I joined TIME Magazine in 1992, one of the things we believed in was the ability of a news organization to separate the “news” from the “noise.”

In the past 20 years, the noise has multiplied and the traditional news organization has shrunk to the point where it often lacks the ability to be heard above the din. Media consolidation has put control of the mass media in the hands of very few people. The audience for news has been fragmented and polarized. In the US, that divides between the Fox News/Drudge Report/Rush Limbaugh vision of the world and The New York Times/MSNBC/Huffington Post way of seeing things. It’s creating a world of misinformation, ignorance, division, and bumper sticker insults offered as wisdom. Meanwhile, the celebrities, business people and politicians covered in the “news” know the game is no longer about telling the truth but about working the refs.

Everyone lies. (And unless they are on our team, it’s unforgivable.)

Facts don’t matter. (That one’s true. Mitt Romney told us.)

You can’t trust anyone. (Not journalists. Not the government. Not the media. Not even Lance Armstrong.)

We now live in an age in which the internet is the newspaper. Where the paper of record has been replaced by the tweet of the moment. Where a journalist’s success is measured not by the quality of her work, but by the traffic it generates. Where a fake news story from The Onion becomes a major feature in China’s People’s Daily and we think that’s funny. Where twice-elected President Obama is either a pragmatic centrist or Hitler, depending on the audience. Where honest debate is polluted by PR people or drowned by trolls. And nothing ever stops. And making sense of the world is literally impossible. It’s an age where you’re either a cynic or a dittohead, so you better pick a side. And, in case I wasn’t clear, print is dead.

Thus concludes The One True Account of the History of News. If you don’t like it, read a different version. Or write one yourself. Believe what you want. The news is all yours.

Do you think that the transition to digital print is a positive or negative move? Leave a comment below..

Image: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 @Doug88888

Bug-a-boo

Wendy M Grossman discusses the encroachment on personal data security by allowing 'back doors' for access by official bodies.

A few weeks ago, Matt Blaze, the head of the distributed systems lab at the University of Pennsylvania, and Susan Landau, published an opinion piece in Wired arguing that the FBI needs hackers, not back doors. This week, they, with co-authors Steve Bellovin, a professor in computer science at Columbia University, and Sandy Clark, a graduate student in Blaze's lab, published Going Bright: Wiretapping without Weakening Communications Infrastructure, the paper making their arguments more formally.

The gist is straightforward enough: when you pass a law mandating the installation of back doors in communications equipment you create, of necessity, a hole. To you, that may be legal access for interception (wiretapping). To the rest of us it's a security vulnerability that can be exploited by criminals and trolls every bit as effectively as one of those unpatched zero-day bugs that keep getting in the news. Like yesterday's announcement that the Federal Reserve's systems had been hacked. So instead of creating new holes, why not simply develop the expertise and tools to exploit the ones that already exist and seem to be an endemic part of creating complex software?

Yeah, no, they're not joking. April isn't for some time yet.

A little more background. In 1994, the US passed the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). It was promptly followed by legislation mandating lawful interception in Europe, Canada, and others. Since then, law enforcement in those countries has persistently tried to expand the range of services requires to install such equipment. In the UK, the current government proposes the Communications Capabilities Development Programme (CCDP) which would install deep packet inspection (DPI) boxes on internet service providers' networks so that all communications can be under surveillance.

There are many, many problems with this approach. One is cost: fellow Open Rights Group advisory council member Alec Muffett has done a wonderful job of pointing that out for CCFP in particular. If, he writes, you require a whole lot of small and medium-sized companies to install a proprietary piece of hardware/software that perforce must be frequently updated, you have just given the vendors of these items "a license to print money".

The bigger problem, however, as Landau has wrote in 2005 (PDF), is security. A hole is a hole: when a burglar who finds an unlocked door isn't deterred by its having been intended solely for the use of the homeowner. The Internet is different, she argues, and the insecurities you create when you try to apply CALEA to modern telephony - digital, carried over the Internet as one among many flows of data packets rather than over a dedicated direct circuit connection - have far-reaching implications that include serious damage to national security.

Nothing since has invalidated that argument. If you'd like some technical details, here's Cisco describing how it works: as you'll see, the interception element creates two streams, sending one on unaltered and sending the other to the monitoring address. Privacy International's Eric King has exposed the international trade in legally mandated surveillance technologies. Finally, as Blaze, Landau, Clark, and Bellovin write here, recent years have turned up hard evidence that lawful intercept back doors have been exploited. The most famous case is the 2004 pre-Olympic incident in which more than 100 Greek government officials and other dignitaries had their cellphones tapped via software installed on the Vodafone Greece network. So their argument that this approach is dangerous is, I think, well-founded.

The FBI, like other law enforcement services, is complaining that its ability to intercept communications is "going dark". There are many possible responses to that, and many people, including these authors, have made them. Even if they can no longer intercept phone calls with a simple nudge to a guy in a control room at AT&T in the US or BT in the UK, they have much, much more data accessible to them from all sorts of source: surveillance has become endemic. And the decades of such complaints make it easy to be jaded about this: it was, 20 years ago, the government's argument why the use of strong cryptography had to be restricted. We know how that turned out: the need to enable electronic commerce won that particular day, and somehow civilisation surived.

But if we accept that there is a genuine need for some amount of legal wire-tapping as a legitimate investigative tool, then what? Hence this paper's suggestion that a less damaging alternative is to encourage the FBI and others to exploit the vulnerabilities that already exist in modern computer systems. Learn, in other words, to hack. Yes, over time those vulnerabilities will get closed up, but there will inevitably be new ones. Like cybercriminals, law enforcement will have to be adept at adapting to changing technology.

The authors admit there are many details to be worked out with respect to policy, limitations, and so on. It seems to me inevitable – because of the way incentives work on humans – that if we pursue this path there will come a point where law enforcement or the security services quietly pressure manufacturers not to fix certain bugs because they've become too useful. And then you start wondering: in this scenario do people like UCL's Brad Karp, whose mission is to design systems with smaller attack surfaces, become enemies of the state?

Wendy M. Grossman’s web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of the earlier columns in this series.

Adblocking: a new legal battleground?

"It would be draconian, as well as practically impossible, to attempt to prevent users from carrying out their own ad-blocking." Guy Burgess examines possible the legal challenges to ad-blocking software.

Guy Burgess is a New Zealand lawyer.

Consider these two facts:

Fact 1: many of the world’s largest internet companies, including Google and Facebook, derive most of their revenue from serving up online advertisements.

Fact 2: one of the most popular browser add-ons is Adblock Plus, free software designed to eliminate online advertising from a user’s browser, with the Firefox version alone recording close to one million downloads per week.

You don’t need to be a financial guru to see the potential problem here. Could browser ad blocking one day become so prevalent that it jeopardises potentially billions of dollars of online ad revenue, and the primary business models of many online and new media businesses? If so, it will inevitably face legal attack.

The concept of browser ad blocking software is simple: when a user opens a web page, the software detects any advertisements included in the page and automatically removes them while leaving the rest of the page intact. The user gets to view just the content they wanted (for example, the article or page of search results) without being bothered by banner ads, sponsored links or other advertising. Other claimed benefits include faster loading pages, reduced bandwidth, and reduced tracking of surfing habits. There is little if any downside for the user, but a big potential downside for the website and its advertisers whose paid ads are silently zapped before being seen – and perhaps clicked on – by the user.

Currently, advertising-supported sites seem unperturbed. Google itself – the world’s largest online advertising provider – offers Chrome-versions of Adblock directly from its official Chrome Web Store (somewhat incongruously boasting that it can even block video ads from Google’s own YouTube site). And there seems little cause for concern at present: online advertising is thriving, which suggests that ad blocking is not, statistically, too widespread.

Overall statistics on browser ad blocking are hard to come by, but Mozilla records over 178 million total downloads of Adblock Plus and over 14 million average daily users for its Firefox browser alone. Even when extrapolated over all browsers, this still only represents a small percentage of web traffic. Whether this will grow significantly remains to be seen. There are also technical ways in which websites try to defeat ad-blockers, but this is somewhat of a cat-and-mouse game between developers, with dynamically-updated filter lists and other techniques giving ad-blockers the upper hand. What legal steps might be taken if browser ad blocking does reach a point where it is seen as a threat to bottom lines and business models?

The legal position

There does not appear to have been any court case to date involving browser ad blocking. This may be an indicator of the lack of concern or loss, or of the difficulty of such a legal challenge, however there have been some US legal battles involving other forms of ad blocking/skipping that help set the scene for future legal fights.

An early example arose in the famous US “Betamax case” proceedings of the late 1970s and early 1980s in which studios challenged the legality (under copyright law) of home video recorders. The studios claimed, in part, that “the commercial attractiveness of television broadcasts would be diminished because Betamax owners would use the pause button or fast-forward control to avoid viewing advertisements”. The Court rejected that claim because, it said, the viewer must still receive and record the commercials and then “must fast-forward and, for the most part, guess as to when the commercial has passed”, a process which the Court said “may be too tedious”.

Fast-forward to 2002, when several US networks sued the maker of the ReplayTV DVR in part due to its commercial-skipping features, alleging that such technology “attacks the fundamental economic underpinnings of free television”. The case effectively ended after ReplayTV went into bankruptcy a short while later, so no legal precedent was set.

In a 2003 case involving file-sharing service Aimster, prominent judge Richard Posner wrote that, based on earlier cases, commercial-skipping “amounted to creating an unauthorised derivative work … namely a commercial-free copy that would reduce the copyright owner’s income from his original program, since ‘free’ television programs are financed by the purchase of commercials by advertising”. However, commercial-skipping was not the focus of that case.

The issue was revived earlier this year, with CBS, Fox and NBC suing Dish Network over its commercial-skipping technology, saying they were doing so “in order to aggressively defend the future of free, over-the-air television”. The legal basis of (part of) the claim is, in essence, that commercial-skipping infringes copyright by modifying the broadcast stream presented to end users.

It is not a particularly big leap to apply those arguments to browser ad blocking.

Could a legal attack be launched on browser ad blocking?

Two areas of law that could potentially be used in efforts to attack the legality of browser ad-blocking are:

1. Copyright law: it could be claimed that ad blocking constitutes copyright infringement, by causing unauthorised modification to a web page (which in many cases will be protected by copyright) – that is, it creates an unauthorised adaptation of the page. As mentioned above, this has been the basis of television commercial-skipping lawsuits, and has received supportive comment from US courts.

2. Trade practices / commercial laws: it could be claimed that the use of third party software to remove paid advertising constitutes interference with contractual relations, e.g. an advertiser and a website have entered into a contract whereby the site will display an advertisement in return for a fee or commission, but this arrangement is being intentionally stymied by ad blocking software. Alternatively, it could be claimed that ad blocking software induces the breach of website terms and conditions that prohibit ad-blocking (if such a term is present, which currently is relatively uncommon).

Both of these scenarios have significant legal and practical challenges in the context of browser ad blocking, but are not inconceivable if the targets are the identifiable distributors of the ad blocking software or the maintainers who update “filter lists” that the blockers commonly rely on, as opposed to targeting end users. Likewise, if a browser distribution started to bundle and enable ad-blocking features by default, it could become a target for legal action.

Another possibility is specific regulation, where a law is passed that specifically bans the use or distribution of ad blocking software. Similar precedent is found in laws banning the sale of digital rights management “circumvention devices”. For example, New Zealand’s copyright law bans the sale or distribution of such devices in certain circumstances but notably does not ban the private use of DRM circumvention devices. This partly reflects policy decisions about intellectual property and user rights, but also acknowledges the practical difficulty of banning private use of such devices. It would be draconian, as well as practically impossible, to attempt to prevent users from carrying out their own ad-blocking. Attempts to prevent the creation or distribution of “filter lists” also raises significant freedom of speech issues.

As with file sharing, the billions of dollars potentially at stake will likely prove fertile ground for legal challenges and legislative responses.

You can read more articles by Guy Burgess at www.burgess.co.nz

Image: CC BY 2.0 atomicjeep

Privacy in the balance - as always!

Nigel Waters talks about the future of privacy: the battle between those who want to monitor us for their own gain, and those who want to preserve an individual's right to privacy.

Nigel Waters has a wealth of experience from across the privacy spectrum. He has been the deputy Commonwealth Privacy Commissioner of Australia, and currently works for Privacy International and is Public Officer of the Australian Privacy Foundation. He is a visiting fellow at the University of New South Wales Law Faculty.

With another international privacy day just passed, individuals worldwide face the same threats to their privacy as in previous years, but with perhaps a little more hope of protection, through a combination of laws, enforcement, civil society mobilisation and ‘privacy by design’.

Governments and businesses continue to press for ever-greater monitoring and surveillance, in all areas of life from transport to health care. Governments justify it on the basis of meeting law enforcement, efficiency and genuine service provision objectives. Businesses claim that greater knowledge of existing and potential customers allows them to better meet peoples’ needs, but are understandably motivated primarily by commercial objectives.

Both governments and businesses are reluctant to offer individuals real choice about how much personal information they are prepared to share – arguing that in many cases this would compromise the other public interest (or commercial) objectives. The reality is that many current business models, in both the private and public sectors, assume or demand universal access to information about people’s circumstances and activities. Increasing emphasis on data aggregation (Big Data) increase the pressure on a ‘private sphere’ and use of cloud computing services re-awakens a longstanding issue about who is responsible for data processed by one organisation on behalf of another.

The good news is that lawmakers continue to recognise and respond to these threats – the number of jurisdictions with information privacy or data protection laws passed 70 in 2012. While they vary in their strength, most include not only detailed rules but also complaint and enforcement mechanisms and sanctions, rather than relying on weak self-regulatory schemes. Under most laws, there are at least semi-independent supervisory privacy enforcement authorities (PEAs), and there has been progress in recent years in setting up processes for cross-border enforcement co-operation – with some high profile cases including investigations into Google, Facebook and Sony amongst other businesses.

PEAs increasingly also liaise on common public sector issues such as law enforcement information exchanges and biometric identification – seeking to minimise privacy intrusion while meeting legitimate public interest objectives. An increased use of privacy impact assessment (PIA) at the planning stages of new systems should make it easier to strike this balance, although government agencies remain resistant to effective use of PIAs and the technique has not yet taken root in the private sector.

In the last few years, many high profile data security breaches have led to a new strand of regulation – mandatory security breach notification requirements – either alongside or within existing information privacy laws, and these requirements are arguably doing more to focus senior management attention on privacy principles than 30 years of human rights based data protection laws have been able to achieve. Commercial risk – whether in the form of financial losses or reputational damage is clearly a more powerful motivator than mere compliance or altruism.

Civil society has become better organised both in individual countries and internationally, with a formal seat at the table in privacy discussions at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and greater opportunities for input at other international forums such as the EU, the Council of Europe and the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners, though not yet at Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) or in closed door intergovernmental trade negotiations such as the Anti-counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) and the Trans-pacific Partnership (TPP). However, civil society capacity remains minuscule relative to the resources that business groups can and do devote to lobbying in all these forums.

Major reviews of the main international privacy instruments – the OECD Guidelines, the Council of Europe Convention 108 and the EU Directives - are in progress and to date seem to be ‘holding the line’ against attempts by some government and business interests to weaken these foundation principles. There continues to be legitimate debate about the practical effectiveness of current regimes, focusing on the concept of accountability, which has many different meanings. There is a broad consensus on the need for organisations to demonstrate their compliance with privacy rules – but not on the extent to which a data controller’s acceptance of responsibility can substitute for detailed compliance requirements and close supervision by independent PEAs, and for effective controls on cross-border data transfers.

2013 will no doubt throw up some new privacy challenges, from new technologies and business models, but they are likely to be variants on existing issues rather than fundamentally different. As always, the real challenge will remain the willingness, and capacity, of societies’ institutions to say no to some superficially attractive initiatives in the name of preserving individuals’ right to a private life as a key manifestation of human autonomy and dignity.

Image: CC BY-SA 2.0 Edith Soto

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.