Humans Have No Default Setting

Loz Kaye, Leader of the Pirate Party UK, looks at why the Snoopers Charter has crawled its way back into the political agenda, and why it will it may not solve the problems that politicians are hoping it will.

Looking at the news, Britain feels quite a grim place at the moment. From Woolwich to Wales high profile murders have left us wondering who we are as a nation - and how we stop such atrocities in the future. Over the years I can't count the times I have looked away from the tabloids in the local Coop with the haunting repeated images of the latest missing or murdered child wishing it would just stop.

The responsibility for trying to make it stop falls, to great degree, on our politicians. It seems many have the same wish, that there would be one easy thing to do that could make it go away. As so often, technology is given the blame, it's the Internet's fault and Google's "deadly web of poison and hatred" as the Daily Mail would have it. From casual use of computers and phones, it is tempting to think there is an easy off switch. Basically the only concrete thing the government and opposition have offered as a response to recent events is surveillance, web blocking and filters.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragic events in Woolwich the likes of Theresa May and Labour's Lord Reid were quick to call for the return of the Snoopers' Charter. The implication was that its blanket surveillance powers would somehow have prevented a thuggish street attack, with the Home Secretary claiming that it was part of giving law enforcement "the tools that they need".

However, no one has demonstrated in a concrete way how the CDB would have prevented this particular incident, with security service sources saying in fact it would not have helped. Lord Reid seems to suggest that increased blanket powers would deal in a general way with a great nebulous threat he paints. This is despite for example Danish police recently reporting that data retention has not helped them, in fact the information is described as "unusable".

This boils down to political opportunism, a chance to take a pot shot at all of us who have fought to protect civil liberties. Even MI5 sources characterised this as cheap.

The other side of the Internet blame game since Woolwich has been laying the responsibility for radicalisation at the door of "Sheikh Google", with impressionable young people creating their own cut and paste ideology. This is hardly a new approach, the 2011 Prevent strategy review to deal with countering domestic extremism declared "Internet filtering across the public estate is essential".

Even so, the very same document concedes that there is not the evidence to back this up nor is there the capacity to do it: "We do not yet have a filtering product which has been rolled out comprehensively across Government Departments, agencies and statutory organisations and we are unable to determine the extent to which effective filtering is in place..." The situation on the ground is fundamentally the same as two years ago. No new powers over the Internet were called for when Theresa May said it was "a strategy that will serve us well for many years to come". What has changed since then, other than a desire for sound bites about hate preachers?

Similar calls have come in the wake of the most distressing crimes I think most of us can conceive of, the death of young children. Once again the speed to which some commentators have used specific cases to push a particular agenda is profoundly unsettling. This has also come from quarters which should frankly know better. The Guardian editorial which wilfully mixed together legal images and records of attacks on children to make a case for "banning Internet pornography", however they think that might be achieved, was deeply irresponsible.

Let's be clear. Images of attacks on children are evidence of crimes. I, and society at large, expect these crimes to be investigated, that has always been the case and nothing has changed about that.

However, there is no way to get from that to the calls like John Carr 's for Google to change its default settings, or the more diffuse thundering that 'something should be done' by the tabloids. Agreeing that you are 18 plus is hardly a high barrier, and it is not even likely that this will happen in the way Carr describes. Nor is there evidence that further restrictions would be productive. Much is made both in relation to extremism and pornography to the increasing ubiquity of the Internet and availability of material. But there is no demonstrable surge in sexual assaults attributable to this factor.

Moreover, where blocking has been tried it has been found to be ineffective, in the Netherlands for example the Internet Safety task force found filters did not "contribute to the jointly formulated goal and therefore cannot be employed effectively". While there is not evidence to back up blocks benefitting the social good, what we do know is the collateral damage such attempts make. ORG has clearly demonstrated the effects of over blocking on mobile networks.

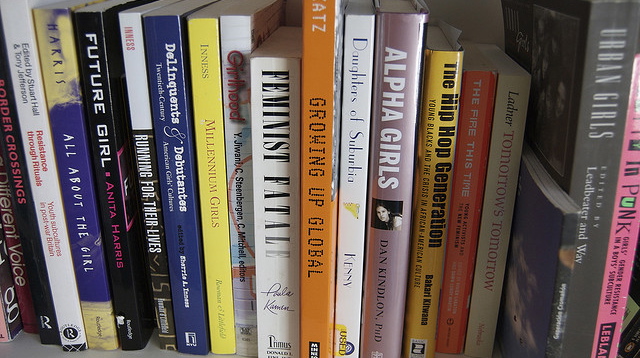

David Cameron has been promising "good, clean WiFi" in public spaces to give parents peace of mind. But he is not in a position to offer any such thing. We should not be in the business of outsourcing moral choice, nor encouraging parents to think it is possible, let alone desirable. Nor should we just focus on just one part of culture and society, however fashionable it is to hold forth about the web and social media at the moment. I haven't seen calls on the Publishers' Association to somehow make bookshops default 18 plus following the 50 shades of profit their members have made from erotica. Even if we wish it otherwise, the uncomfortable truth is this. Humanity does not have factory settings. There is no button to push to make evil stop.

There are always a huge number of complex factors that feed in to complex social problems. The Prevent strategy highlights a range of settings which are important in addressing radicalisation - the criminal justice system, schools, universities, health delivery, faith institutions and organisations, prisons and probation. One can say the same about attacks on children, and of course many institutions have a role to play in combatting them, perhaps not least the Catholic Church.

To make the Internet the key factor is wrong headed. Two major elements identified in Prevent as to why people are attracted to extremism are being in a lower socio-economic group, and that extremist views are "significantly associated ... with experience of racial or religious harassment".

It is vital that as a digital rights movement we do not just protect our interests, without taking a wider interest in the society in which we take part. That will rightly lay us open to the charge of being shortsighted and anti-social. But of course poverty, abuse and racism are difficult to deal with. It is far more attractive for politicians to blame the Internet when they are under pressure from the tabloids. It's simpler to hold out promises of magic technological solutions even if they have no basis in reality. In austerity Britain it's cheaper to make social policy Google or BT's problem, and their expense. But this is lazy thinking, and worst of all will do nothing to address the full range of causes of some of our most worrying problems. We may yet come to pay dearly for current politicians' lack of imagination.

Image: Ostrich in the Serengeti, Tanzania by Iode.rummers CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Is 'Data Protection Regulation' really too much of a burden?

Professor Douwe Korff gives his thoughts on the ICO's letter to the Ministry of Justice on the 'Data Protection Regulation'

The "Data Protection Regulation" is currently being discussed by European policy makers. We think it could offer better privacy protection and give people more control over their data, which is much needed. The Ministry of Justice and the Information Commissioner's Officer have both expressed concerns about the proposals, however, suggesting the new law could be too burdensome. The Information Commissioner recently wrote to the Secretary of State Chris Grayling at the Ministry of Justice setting out his overarching concerns.

Here, Professor Douwe Korff gives a quick, off-the-cuff immediate commentary on the letter.

(You can read the ICO's letter here )

After paying some lip service to the importance of data protection, this is a typically negative attitude by the ICO to any worthwhile data protection regime. Here are my specific comments on his main points of criticism:

"...too much emphasis on punishment in stead of awareness raising and education"

Read: the ICO wants to continue with its useless "lets sort this out between friends" approach to big business (just like the HMRC deals with big corporations). It is not totally toothless, but basically refuses to bite (other than in one or two show cases against local authorities losing millions of records repeatedly).

"only data breaches that pose 'significant risk' should have to be reported to the ICO, otherwise it would cause too much work"

Comment: This would leave it to businesses themselves to assess if there is such a serious risk that they should report their own failures. It would result in most security breaches still going unreported and undetected. How much work is it for the ICO to quickly sift through reports of minor breaches, to fish out the more serious ones?

The ICO is against "prior authorisation" for some international data transfers.

Comment: this is a crucial safeguard that should remain in the regulation. again goes to show the ico doesnt really care about our data protection rights and interests.

The Information Commissioner doesnt want to be forced to impose administrative sanctions for mere "process failures" which did not lead to real privacy risks.

Comment: He basically doesnt like enforcing the law, but he ought to! what is he there for?!

He doesnt like having to take part in the "consistency mechanism"; it is "insufficiently risk-based" and "contains unrealistic time-limits".

Comment: The consistency mechanism is essential to ensure that the regulation is applied the same throughout the EU, and interpreted strictly (rather than arbitrarily and loosely, as is the case with the ICO's approach to the UK DPAct and the current DP Directive)! it again goes to show that he really wants to keep the UK as a country where data protection is not seriously enforced, even by the national DPA.

Oh, and of course he isn't asking for serious money to uphold our fundamental rights:

"... given the state of public finances across the EU and the more obviously higher priority causes competing for public funding, it is surely questionable that there will be more money available for DPAs than there is now."

Comment: At the moment, the ICO costs only £16 million a year, which is about 25p per citizen ...

To learn more about the Data Protection Regulation and how to contact your MEP, see the campaign website Naked Citizens.

#FBrape

Does the #FBrape campaign challenge our freedom of speech? Are feminists censoring the internet? Soraya Chemaly, one of the founders of the campaign, gives her insight into the issue.

Last week, I along with Jaclyn Friedman of Women, Action and the Media and Laura Bates, of Everyday Sexism, led a movement challenging Facebook's policies about content moderation. Facebook responded by saying it had failed to deal adequately with misogynistic content depicting violence against women and outlined the steps it would take to change a cultural tolerance for violence against women. The social activism, which involved raising awareness and asking advertisers to boycott the company until it acted in accordance to its own terms and guidelines, is notable because it is a rare public acknowledgement that misogyny and sexism are real, that they are harmful. Corporations, like Facebook, have a responsibility to treat hate based on gender in the same manner that they do other forms of hate speech.

Many people are saying this is a case of feminists censoring the Internet. I'd like to address this head on to explain why this is not the case. As a feminist and a writer, I understand free speech and hold it dear, but there are two issues being conflated in the concern that #FBrape, the name of the campaign in social media, will reduce speech. One is: how does Facebook regulate speech in its service? The second is: SHOULD Facebook be regulating speech?

Our initiative dealt with number one, how is Facebook regulating speech? Facebook is clearly regulating speech - they have a moderation policy and a detailed reporting and review process. The issue is that they were not interpreting these processes in a way that treated girls and women fairly and equally. That was the issue addressed in our program.

Page with names like "Raping Your Girlfriend," and text and images of popular rape memes depicting about-to-be-raped, incapacitated girls were easily found. Pictures and videos of girls and women frightened, humiliated, bruised, beaten, raped, gang raped, bathed in blood, and, in a recently publicized case, beheaded were "liked" by tens of thousands. In a milder example that went viral through our campaign, Facebook declined to remove an image of a woman, mouth covered in tape, in which the caption read, "Don't tap her and rap her. Tape her and rape her." Facebook's response to readers who reported it read, "We reviewed the photo you submitted, but found it did not violate our community standards."

Content like this defied reason and Facebook's own terms, which prohibit posts that "attack others based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, disability or medical condition."

Facebook "censors" content every day already. The company had in place the formal language of a reasonable content policy geared toward ensuring users' safety, but it was not implementing it effectively. This failure disproportionately affected girls and women. That is why we demanded that the company reassess it's definition and interpretation of "hate speech" and train moderators to recognize why violence against women is a real problem and, when graphically represented in the ways found, hateful and threatening,

This content isn't "offensive". The photographs and videos we found depict gross human rights violations for the cruel use, entertainment and profit of others. The offense is that these depictions are considered funny or controversial.

Facebook is not "the internet." We chose it because it had content and community guidelines. The company, with more than a billion users, is an influential force. It is both a mirror and a microcosm of a global culture. As such, it is no more or less sexist or misogynistic than any other company or aspect of media. However, by creating a review process it became an arbiter of norms and provided a way to challenge those that encourage and perpetuate gross and easily demonstrable prejudices against girls and women. We are hopeful that this is a first step in making safer spaces both online and off.

The question of WHETHER Facebook should have a content moderation and review process is an entirely separate one.

Soraya Chemaly is a cultural critic and feminist activist. Her work and writing focuses on the role of gender in culture, in media, politics, religion and more, with am emphasis on the role that sexualized violence plays in sex-based prejudices and gender inequality.

Forcing functions

Will open data support values of democracy, openness, transparency, and social justice? Wendy M Grossman explores the question.

At the recent OpenTech, perennial grain-of-sand-in-the-Internet-oyster Bill Thompson, in a session on open data, asked an interesting question. In a nod to NTK's old slogan, "They stole our revolution – now we're stealing it back", he asked: how can we ensure that open data supports values of democracy, openness, transparency, and social justice? The Internet pioneers did their best to embed these things into their designs, and the open architecture, software, and licensing they pioneered can be taken without paying by any oppressive government or large company that cares to. Is this what we want for open data, too?

Thompson writes (and, if I remember correctly, actually said, more or less):

…destruction seems like a real danger, not least because the principles on which the Internet is founded leave us open to exploitation and appropriation by those who see openness as an opportunity to take without paying – the venture capitalists, startups and big tech companies who have built their empires in the commons and argue that their right to build fences and walls is just another aspect of ‘openness’.

Constraining the ability to take what's been freely developed and exploited has certainly been attempted, most famously by Richard Stallman's efforts to use copyright law to create software licenses that would bar companies from taking free software and locking it up into proprietary software. It's part of what Creative Commons is about, too: giving people the ability to easily specify how their work may be used. Barring commercial exploitation without payment is a popular option: most people want a cut when they see others making a profit from their work.

The problem, unfortunately, is that it isn't really possible to create an open system that can *only* be used by the "good guys" in "good" ways. The "free speech, not free beer" analogy Stallman used to explain "free software" applies. You can make licensing terms that bar Microsoft from taking GNU/Linux, adding a new user interface, and claiming copyright in the whole thing. But you can't make licensing terms that bar people using Linux from using it to build wiretapping boxes for governments to install in ISPs to collect everyone's email. If you did, either the terms wouldn't hold up in a court of law or it would no longer be free software but instead proprietary software controlled by a well-meaning elite.

One of the fascinating things about the early days of the Internet is the way everyone viewed it as an unbroken field of snow they could mold into the image they wanted. What makes the Internet special is that any of those models really can apply: it's as reasonable to be the entertainment industry and see it as a platform that just needs some locks and laws to improve its effectiveness as a distribution channel, as to be Bill Thompson and view it as a platform for social justice that's in danger of being subverted.

One could view the legal history of The Pirate Bay as a worked example, at least as it's shown in the documentary TPB-AFK: The Pirate Bay – Away From Keyboard, released in February and freely downloadable under a Creative Commons license from a torrent site near you (like The Pirate Bay). The documentary has had the best possible publicity this week when the movie studios issued DMCA takedown notices to a batch of sites.

I'm not sure what leg their DMCA claims could stand on, so the most likely explanation is the one TorrentFreak came up with: that the notices are collateral damage. The only remotely likely thing in the documentary to have set them off – other than simple false positives – is the four movie studio logos that appear in it.

There are many lessons to take away from the movie, most notably how much more nuanced the TPB founders' views are than they came across at the time. My favorite moment is probably when Fredrik Tiamo discusses the opposing counsels' inability to understand how TPB actually worked: "We tried to get organized, but we failed every single time." Instead, no boss, no contracts, no company. "We're just a couple of guys in a chat room." My other favorite is probably the moment when Monique Wadsted, Hollywood's lawyer on the case, explains that the notion that young people are disaffected with copyright law is a myth.

"We prefer AFK to IRL," says one of the founders, "because we think the Internet is real."

Given its impact on their business, I'm sure the entertainment industry thinks the Internet is real, too. They're just one of many groups who would like to close down the Internet so it can't be exploited by the "bad guys": security people, governments, child protection campaigners, and so on. Open data will be no different. So, sadly, my answer to Bill Thompson is no, there probably isn't a way to do what he has in mind. Closed in the name of social justice is still closed. Open systems can be exploited by both good and bad guys (for your value of "good" and "bad"); the group exploiting a closed system is always *someone's* bad guy.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted irregularly during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Can a VPN protect you from government surveillance?

Nick Pearson explains the functions of a VPN, and how to best choose one that will ensure your privacy is protected.

As the global debate over online government surveillance rages on, it's reasonable to assume the use of privacy tools to foil state-spying efforts will only increase. The protection of online privacy is already a booming industry online, with a number of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), claiming to protect your data from government intrusion. VPNs can do a lot of things, such as allowing you to get around regional YouTube restrictions, or helping you escape the online parameters of whatever censorious regime you may be living under. But can they really stop governments from accessing your data, and what will happen if a government asks an VPN for information on a customer?

What is a VPN?

A VPN, to quote Wikipedia, “enables a host computer to send and receive data across shared or public networks as if they were an integral part of the private network with all the functionality, security and management policies of the private network.” A VPN in the context of a privacy platform, is a network that ensures all the data you’re sending and receiving is encrypted and never logged, thus preventing spying. But while the acronym “VPN” has become a byword for online privacy, not all VPNs are actually privacy services – and even the ones that are may not be serious about protecting privacy.

Data retention

The key issue concerns the storing of data. The European Data Directive mandates that all ISPs must store user data, which includes logs of who you've emailed and logs of what websites you've visited, for at least one year after the user leaves the ISP's service. In the US, there is no data retention law – although that may change – but ISPs are free to store data for as long as they like, and many happily do so in order to better assist law enforcement. Whether or not a VPN can protect your privacy revolves around the integrity of its own data retention policy.

A study from TorrentFreak shows, many VPNs retain user data in exactly the same way as an Internet service provider (ISP), which renders them pretty much useless as a privacy service. VPNs have to abide by the laws in their jurisdiction. If law enforcement demands a VPN hand over its data on a customer, then they must comply. But if there's no data to hand over, then a user's privacy is always protected. Sure, law enforcement could demand a VPN start logging data on a particular user (which is probably what happened in the case of HideMyAss and Lulzsec), but any VPN serious about privacy would shut down the service before complying with such an order.

Some VPNs retain data because it essentially makes their lives easier and is used to troubleshoot problems with the network. Others retain data because they believe it's necessary to comply with the law – even though that may not be the case. If they are honest, such VPNs would not market themselves as a privacy service. But not all are honest; some downright lie, and others simply hide behind the conflation of the words 'VPN' and 'privacy'.

How to choose a VPN

So if you want to use a VPN for privacy purposes, what should you do? Firstly, examine the VPN's terms and conditions closely. Make sure it's very clear about how long it stores data. If in doubt ask them. Most genuine privacy services will only retain data for a few hours maximum. Secondly, find out what the VPN will do if the laws in its jurisdiction concerning data retention changes. Any privacy service worth its salt, should be prepared to move jurisdiction if changing laws compromise user privacy (admittedly there's some grey areas here, but a commitment to moving jurisdiction is a good sign the VPN takes privacy seriously). Finally, ask the VPN how far it's willing to go to protect the privacy of its users in the face of demands from law enforcement. You may not get a straightforward answer to this question, but if a VPN has built its business on privacy commitments then it's more likely to put-up as much resistance as possible to protect its business' reputation.

Nick Pearson is the founder of IVPN. IVPN is a VPN privacy service and Electronic Frontier Foundation member aimed at journalists, people living in areas of online censorship, and privacy-conscious individuals.

Image: Caméra de vidéo-surveillance by Frédéric BISSON CC BY 2.0

Who are the BPI's new website blocking targets?

James Brandes looks at the torrent sites, filesharing aggregators and streaming services in the firing line, and asks if the fat lady sung for Grooveshark?

James Brandes is a Copyright Agent who operates the Digital Copyright Consultancy. The Digital Copyright Consultancy provides anti-piracy protection for a wide variety of clients' in the music and adult entertainment industries. It has worked on 4,000 + assignments for 82 clients' and has removed over 5,000,000 infringing links and search results. Projects have ranged from providing piracy protection services for Digital EP releases to well known dance compilations/rock albums and adult DVD releases/website content.

The British Phonographic Industry (BPI) is on the warpath and is targeting torrent sites, file sharing aggregators and streaming services. In their continuing battle against websites that allegedly contain or provide search capability of unlicensed music content, the BPI will likely ask Internet Service Providers to voluntarily block these sites in the first instance. Should that fail however, costly litigation via the High Court seems a conceivable consequence. Earlier this year; 3 torrent sites (KickAssTorrents, H3TT and Fenopy) were all blocked in the UK at the ISP level following on from the high profile blockade of notorious torrent site The Pirate Bay. Serious questions must now be asked about the new list.

The Pirate Bay still refuses to remove torrent search results, KickAssTorrents has been similarly recalcitrant in the past year and H3TT charges content owners / their agents to send Notices for removal of infringing material. But there are sites that take a different approach to responding to Copyright Infringement Notices. I'll explain how and why they're different.

The list compiled by the BPI and its members is a mixture of BitTorrent sites, file sharing aggregators, streaming services and pirate link sites that upload content to one-click file hosting services. Some are more contentious than others. In this article, I'll largely talk about services that I've dealt with extensively through my anti-piracy activities.

Starting with Torrent sites, it should always be borne in mind that BitTorrent is a technology which in itself is legal. However, the legality of many of its uses has been, and currently is being aggressively litigated worldwide. It's probably fair to say that the vast majority of Torrent administrators know that their service is used by many to distribute unlicensed content. Furthermore, they've made a lot of money off the back of advertising revenue. As a consequence, it's somewhat understandable that content owners/their agents and copyright protection bodies want to take action against them.

However, whilst I remove a great deal of content from one-click file hosting services, torrents and even search engines such as Google, I feel distinctly uneasy about the blocking of websites in their entirety. At what stage should it be considered? Is wholesale website blocking a step too far? And is it actually effective? Some technology commentators have their doubts.

If we take a look at BitSnoop first, it indexes over 20 million torrents in its database. I think it'd be a reasonable assumption that the site owners know that a fair amount of content found by its torrent search engine is unlicensed. But the site, in its defence,responds extremely quickly to DMCA/Copyright Notices via an automated DMCA Bot. Offending URLs are in fact removed within minutes.They also publish a list detailing the number of DMCA Notices they've received in the past year. It's interesting reading.

But the plot thickens. If you check the BPI's Google's Transparency Report, you'll see that the BPI have sent DMCA Notices to Google for over 300,000 infringing Bitsnoop URLs. Further investigation via Chillingeffects reveals that few of these Bitsnoop URLs have actually been removed at the source (they're still live) which is a somewhat curious strategy.

Is there an ulterior motive to make Bitsnoop look bad? Debatable, but I'm certainly of the opinion that the BPI should remove the allegedly infringing content from Bitsnoop first before considering more draconian measures such as website blocking. Thus, blocking Bitsnoop seems premature at this stage.

Having said that, things can and do often change - KickAssTorrents used to be extremely cooperative with regards to removing torrents/search results, yet for some inexplicable reason have largely stopped cooperating with content owners and their agents.

Just over 2 years ago, torrent search engine IsoHunt was forced to implement a keyword filter to block infringing content on behalf of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and nor can it rely on safe harbour provisions provided by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 either. It's the 4th largest torrent site in the world and has been subject to a number of law suits.

IsoHunt usually act within 24 hours to disable URLs. The BPI has sent takedown requests to Google for 310,000 URLs yet if this notice posted at Chillingeffects is anything to go by, then one can presume that most of these URLs are still live. As with Bitsnoop, blocking IsoHunt seems to be a little hasty at this stage and blocking would only be appropriate if this site significantly changed its removal policy.

Some other smaller Torrent sites are also on the list. For instance, TorrentReactor is another torrent site which in my experience, has always compiled with copyright takedown requests promptly and expeditiously. In fact, TorrentReactor personally contacted my business the 'Digital Copyright Consultancy' approximately 1 year ago to ask whether I was satisfied with their abuse team's performance. The answer to that question was yes. The BPI has sent thousands of Notices to Google yet it would appear doesn't send Notices to Torrentreactor as the files are still live.

ExtraTorrent is the 5th largest torrent website in the world. They remove content quickly and efficiently. The BPI has sent close to 200,000 takedown requests to Google. Again, the files haven't been removed at source.

Monova has also been targeted by the BPI. I can report that this site removes infringing URLs on request and has been consistently cooperative for a number of years. Predictably, a quick perusal of Chillingeffects will reveal that the BPI has not removed some of the infringing Monova URLs at their source - they're still live.

Regardless of what you may think about Torrent services like the above (they almost certainly have knowledge of general infringing activity), I don't think web blocking is suitable at present particularly when they already remove infringing URLs after receiving notice of them.

Other services have also incurred the wrath of the BPI. FilesTube is a filesharing aggregator and indexes content from over 100 one-click filehosting services and pirate link sites. It currently indexes in excess of 500,000,000 files and has over 1,000,000 likes on Facebook. The filesharing search engine has the reputation as 'the go to' place if you want to find content uploaded to one-click filehosting sites.

However, whilst its main purpose is to largely index content from one-click file hosting services, they do react extremely quickly and remove infringing search results within an hour of receiving a Copyright/DMCA Notice. In fact, the Digital Copyright Consultancy has removed well over 150,000 search results from FilesTube so far. Other similar sites include Filecrop, Filetram and Rapidlibrary and all remove search results when requested. So blocking these websites in their entirety is perhaps questionable.

New Album Releases is a pirate linking site which makes money via its affiliate arrangements with various pay per click one-click file hosting services (please see a previous article by myself on Open Rights if you need an explanation of this business model) and via advertising. They have operated for a number of years. While they claim via a clumsy disclaimer that they're not responsible for uploading content to one-click filehosting sites and that they're merely a search engine, they've uploaded thousands of albums without the permission of the original content owners. Moreover, they don't remove content on request and constantly re-upload albums even when it's very apparent that the content owner wants it removed.

The one-click file hosting services they upload to are well aware that Newalbumreleases are repeat infringers yet do very little to police their servers or discourage their activities.

Why? It would be commercial suicide to discourage Newalbumreleases' pirate activity, as they're a profitable affiliate which helps to change free downloaders into paying premium members. Consequently, this gives Newalbumreleases carte blanche to re-upload content with impunity. In conclusion, I'd argue that a website block for Newalbumreleases would be more justified.

BeeMP3, Dilandau, MP3juices, MP3lemon, MP3raid and MP3skull all feature in the BPI list but what kind of sites are they? These are MP3 download/search engines that aggregate content from a wide variety of services like 4Shared, Soundcloud and one of Russia's largest social networks, Vkontakte - now called vk.com.

A couple of these search sites have no DMCA/Copyright policy and the others, make it difficult to remove content (long winded takedown forms etc). There's perhaps some justification for web blocking in this case.

Grooveshark is an online music streaming service based in the United States. It's not a stranger to controversy - a law suit by Universal in fact claimed that Grooveshark employees systematically uploaded unauthorised music to the service.As of May 2013, Grooveshark has been sued for copyright-violations by all the major music companies including Warner Music Group, EMI Music Publishing, Universal Music Group, & Sony Music Entertainment. In fact, one of the suits alleged liabilities at $17 billion which seems totally outlandish.

While I can't comment on their DMCA/Copyright Procedures as I've had no experience removing content from their site, their inclusion on this list seems surprising especially considering its size, deep pockets and general visibility of its management on social networks. For example, all the key players have business LinkedIn accounts. This further development is surely very troubling for Grooveshark but I doubt they'll go down without a fight.

On the subject of blocking websites, a number of commentators have questioned its efficacy from the beginning and they perhaps have a point. For instance, research by Torrentfreak has indicated that at least 8% of all Pirate Bay traffic is now provided by proxy services.The Pirate Bay blockade has thus highlighted the problems with regards to web blocking - new domains registered, an abundance of proxy servers and numerous other circumvention techniques have been successfully used.

But even if we discount the efficiency of website blockades at the ISP level, surely an organisation such as the BPI should focus on removing content at its source and then exhausting all subsequent possible avenues before resorting to drastic measures such as website blocking? It is my contention that blocking websites entirely should be a last resort when all other options have failed.

Equality bytes

Does BT need television to compete with other service providers? Should the owners who own the means of distribution be allowed to also own the content it streams? Wendy M Grossman explores the issue of network neutrality.

This week BT announced it would give free access for its residential broadband subscribers to its two sports channels (BT Sport 1 and BT Sport 2) plus US-based ESPN. Is this the moment the UK starts fighting, like the US, over network neutrality?

For years the received wisdom has been that the UK is too different. In both countries the legacy monopoly telecommunications supplier ran into deregulation in the mid-1980s. In the US, that began with the court-ordered break-up of AT&T, leading to the set of seven "Baby Bells", which have since merged back into three, much like the shards of the liquid metal man in Terminator 2. In the UK, it's been government policy to open up BT's network to competitors, and its behavior is closely scrutinized. That's harder to do in the US where so much happens at the state, rather than federal, level.

While both countries have large companies wishing to lock consumers into bundles that include broadband, telephone, mobile, and television, the average British Internet user who cares to look has probably dozens of choices of supplier, not all of whom buy their upstream bandwidth from BT Wholesale. The average American is lucky if they have two.

The bigger differences lie in the way television is funded and provided, partly because of the UK's entrenched public service broadcasting and partly because of geography. Given the US's size, in many areas either you have cable or a satellite dish or you don't have television at all because the nearest broadcast station is too far away. In the UK, terrestrial broadcast blankets the nation and the major broadcasters (BBC, ITV, Sky) have teamed up to offer free satellite (Freesat) and broadcast (Freeview) systems whose array of channels is entirely competitive with cable or paid satellite if you can do without the premium channels (mostly movies and sports). I cut the cord on cable a year ago in favor of Freesat plus an online subscription to the tennis tours.

Given this situation, it's not surprising if BT thinks it needs television content in order to compete effectively with Virgin and other ISPs.

In 2010, the BBC's Rory Cellan-Jones asked the network neutrality question about BT when BT Retail's commercial director referred in an interview about prioritizing network traffic so that television streams would reach consumers uninterrupted. There are, Ofcom told Cellan-Jones at the time, no rules against the widespread practice of traffic shaping, and let's face it: if you're watching a video stream or making a voice call it's a lot more important to get your packets immediately and continuously than if you're loading a Web page or reading your email.

In 2011, BT's announcement of Content Connect raised similar questions; that wholesale service was, again, intended to speed delivery of streaming video by using local servers - which sounds like the kind of content caching that goes on all over the place.

For me, what raised more questions was BT's announcement in June 2012 that it had paid £738 million for the rights to 38 Premier League football games and then in February 2013 that it had acquired ESPN's UK and Irish channels. These channels are the basis of BT Sport, which will broadcast a load of football, in direct competition with Sky (and, they tell me, some women's tennis). We are now talking about the country's most significant telecommunications infrastructure provider competing directly with other companies whose content it carries.

Accordingly, this is the announcement that to me is the serious one. The really vital thing in ensuring network neutrality is not banning practices that speed service but in avoiding giving dominant suppliers leverage over their competitors or incentives to break it. Otherwise, you get discriminatory service - exactly what the EU is investigating Google for. This is the classic first principle of antitrust law: the owners of the means of distribution should not be allowed to also own the content that streams through it.

Two of the best-known cases under the US's 1890 Sherman Act illustrate the point perfectly: the break-ups of the movie studios and of Standard Oil. In the former, the movie studios were required to divest themselves of theater chains; in the latter, the company was broken up into dozens of smaller ones. As in the AT&T break-up, some of those smaller ones - Exxon and Mobil - have merged back together, but by the time they did the landscape had substantially altered.

In some of these cases you could argue that regulatory action was rendered unnecessary because new technologies were about to present them with new forms of competition. The AT&T break-up was in 1984 and separated local and long distance reveues; by 1990 the Internet would have begun threatening the latter anyway - although law professor Susan Crawford argues that the subsequent mergers have undone the break-up's competition benefits. Similarly, Paramount Pictures' break-up in 1949 was rapidly followed by the challenge of television.

We can't bet on such a radical change this time. Instead, BT may become a content supplier to other ISPs while, conversely, in the US Google is building out local fiber. Watch this space.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Image: untitled by Jonas CC BY 2.0

Unravelling 3D Printing and Intellectual Property Laws: From Napster to Thingiverse and beyond

Dr. Dinusha Mendis's article gives an insight into what 3D printing is, and what challenges it will pose to intellectual property laws.

What is 3D Printing?

Additive Layer Manufacturing (ALM) or 3D printing as it is more commonly known, is a computer driven manufacturing technology through which 3D shapes and products are created by printing successive layers of material. By using software programmes such as Computer Aided Design (CAD), Google Sketch-Up and Blender, for example, which has the ability to send descriptions of each individual layer to a 3D printer, a three-dimensional object is created - layer by layer. The technology employs materials such as plastic, resin, alumide, chocolate and metal to print 3D objects. Companies such as Sculpteo amongst others, makes available these material which is sold in weight. Its ability to print almost anything, has paved the way for advances in the medical, transport, food, and the toy and hobby industries amongst others whilst also opening up the doors to the weapons industry leading to the creation of 3D printed guns. Whilst 3D printing is set to revolutionise the manufacturing industry and herald the 'third industrial revolution' it is also seen as a 'disruptive technology'.

Is it a new technology?

The concept of 3D printing is not new and dates back to the 1970's. The first patent for the technology was granted in 1977 to Wyn Kelly Swainson and although it did not lead to a commercially available 3D printer at the time, it paved the way for practical additive manufacturing of 3D parts under computer control. The first commercial 3D printer was launched in 1988 by Charles Hull following a patent for 'Stereolithography' granted to him in March 1986. The reasons for the latest 'hype' surrounding 3D printing are two-fold: (1) the coming into being of an entirely new market for 3D desktop printers; and (2) the reduction in prices. For example, the cost of a build-your-own desk top printer is about £750. A commercial printer, on the other hand, can cost about £1,500 and can go up to more than £600,000.

3D Printing and Intellectual Property Laws: The start of a long battle?

In 2011, Thomas Valenty a hobbyist designed a couple of Warhammer-style figurines, owned by Games Workshops' a British game production and retailing company. The issue was that these figures, although tweaked, were identical to the 'Imperial Guard' figures forming part of the Warhammer series. Valenty uploaded the 3D designs of these figures on Thingiverse, an online platform, which invites people to create and share designs freely for free downloading for anyone with a 3D printer. This led to other fans uploading their own designs - all based on Games Workshop's Warhammerseries which resulted in Games Workshop serving a 'notice and takedown order' on Thingiversein accordance with the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act 1998. Thingiversepromptly removed the files and although the issue was settled amicably, it clearly signalled the start of a battle between 3D printing, Intellectual Property (IP) laws and the personal manufacturing era.

3D printing and Intellectual Property law in the UK

Quite simply, an assessment of the present IP laws in the UK reveal that the existing IP laws were not created with 3D printing in mind and therefore are not capable of dealing with piracy and counterfeiting issues thrown up by this technology. Whilst 3D printing a product may not infringe one element of IP law, it is quite possible that it will breach another type of IP. To complicate matters, a further assessment of the IP laws reveal that the same branch of IP can lead to both infringement and non-infringement of protected products which are 3D printed. For example, whilst under section 10 of Trade Marks Act 1994, it will be an infringement to print a product protected by a trade mark, section 11(2) states that if labelled correctly, infringement can be avoided.

Similarly, in the area of design and copyright laws, the law states in accordance withsections 51-52of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988(as amended)that copyright protection for a sculpture (or work of artistic craftsmanship) is limited to objects created principally for their artistic merit - i.e. the fine arts.The question then is what happens to those designs (blueprints) which are considered 'utilitarian'? According toLucasfilm v. Ainsworth[2011] 3 WLR 487it was held that a 3D object which comes into being from such a 'utilitarian' design document does not infringecopyright. In effect, this means that if a CAD file or model embodying a design, for anything other than an artistic work, is used for creating a 3D printed product, it will be deemed to be a design document for that particular product and copyright will not be infringed by making an article to that design or by copying an article made to the design. However, copying the 'design document' or CAD file without authorisation will constitute an infringement of copyright.

From Napster to Thingiverse - and beyond

A further point arises in relation to the 3D printing of IP protected products for 'private and personal use' if carried out at home for private use. In UK, the lack of a 'private copying' exception has left this a grey area. However, in drawing parallels with the Napsterrevolution, and the recent surge of online platforms in the 3D printing sphere such as Thingiverse, Shapeways, Cubifyand Quirky - the doors are open for litigation on the basis offacilitating and inducing online infringement of copyrightof 3D printed products, which are protected by IP laws. Additive Layer Manufacturing or 3D printing is here to stay and the possibilities are endless - from printing toy soldiers, to guns, to beef and liver transplants.

With 3D printing spreading into a variety of industries, it is time to learn lessons from the past which has shown that implementing draconian IP laws is not the forward. The present author suggests solutions in the form of setting up an iTunes-style store for spare parts, or by licensing 3D files more widely as also explained in her article "The Clone Wars: Episode 1". As such, in moving forward in the '3D printing-IP battleground', the way forward should be to adopt new business models in adapting to this new technology.

Bio

Dr. Dinusha Mendis is a Senior Lecturer in Law and Co-Director of the Centre for Intellectual Property Policy and Management (CIPPM) at Bournemouth University. Dinusha specialises in digital aspects of Intellectual Property (IP) Law, in particular copyright law. Dinusha's recent projects have included considering the challenges to Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) as a result of Emerging Technologies, such as the IP implications of 3D Printing. She is the author of the recently published paper "The Clone Wars": Episode 1 - The Rise of 3D Printing and its Implications for Intellectual Property Law: Learning Lessons from the Past?' [2013] 35(3) European Intellectual Property Review pp. 155-169.

'Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing' book review

Javier Ruiz reviews the book,'Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing' by Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman.

Printing in three dimensions -- or "additive manufacturing" as it is technically known -- has been hitting the headlines recently. The announcement in the USA of the first fully functioning gun almost 100% produced by 3D printing has instantly made millions aware of the potential of this technology. It has also prompted calls for its regulation. But in Lipson and Kurman's book, weaponry is among the least disrupted sector in the advent of 3D printing. Why limit yourself to printing a gun, when you can print a heart?

This may sound far fetched, but researchers at Cornell University are already working on printed heart valves, and other printed body part replacements, such as bones, are now routine. Bioprinting has moved from science fiction to the news. Only recently researchers at Princeton have managed to print a bionic ear. In fact it is difficult to think of an area not touched by 3D printing as we go through similar jaw-dropping examples in almost every imaginable human activity.

Art and fashion are obvious candidates, and here imagination knows no limits. Artists are printing organically shaped tables, and chain mail clothing made of interlocking pieces that have been created together. In education, 3D printers are slowly finding their way in, but also out of the STEM and vocational boxes to start influencing general teaching and learning. This is similar to the way that computers left the IT lab behind to become embedded in every aspect of education. Digital cuisine is apparently seeing huge developments, as people mod their printers to fit anything edible that can be squeezed through nozzles. The octopus shaped cornbread looked particularly good, but ultimately this is not that different from fast food fries or Pringles.

These examples are at the cutting edge, but 3D printing is already mature in standard industrial design, with rapid prototyping of car and computer parts the norm. The impact on mass production is yet to be realised however. Lipson and Kurman believe that 3D printing will transform manufacturing but will not necessarily replace mass produced cheap goods. Instead it will allow for the development of new types of industry. Localised, nimble manufacturing of personalised goods in small batches will stretch the market power of the long tail. At present, communities of designers and manufacturers flourish at online places such as Thingiverse, Shapeways and 100kGarages, and are already redefining the relationship between producers and consumers. Some of the pioneers in this area of DiY are even printing the printers themselves, such as the RepRap.

The examples above are great to lighten up dinner table conversations, but the book is not simply a futuristic cabinet of curiosities. There are highly approachable introductions to the technologies and processes. If you ever wondered what the differences between stereolithography (SL) and laser sintering (LS) are, then this book is for you. A particularly interesting section deals with the symbiotic relationship of 3D printing with design software, an often overlooked constraint on what is currently possible. Most contemporary CAD software evolved from industrial machining based on cuts and grinds, and carries some inherent limitations that will take some time to overcome.

Equally important are the materials available. There is a growing range of options to suit most tasks; mainly plastics, but also metals and organic materials - who would have guessed that powdered crab shell would be ideal? In industry the challenges come from finding more environmentally friendly and recyclable materials, composites of conductive and non-conductive materials to allow for the printing of electronics and reactive materials that change their properties to suit conditions. But the ultimate goal is to move to "digital materials" that are composed of discrete units called voxels. The same way that a 2D screen is composed of pixels, 3D printers one day may pile up three-dimensional dots with specific properties that combined will allow for the creation of any object.

This book is unabashedly optimistic about the potential of this technology to change the way we humans make the world, and it is hard not be infected by the clear passion and knowledge of the authors. However, that is not to say that it has the tendency to get annoyingly rose-tinted. Lipson and Kurman carefully explain where the state of the art lies right now, where are the obstacles to the utopia, and what we can realistically expect in the foreseeable future. They also consider the ethical, social and legal implications.

Besides considering the currently small risks from the creation of weapons and designer drugs, the authors see consumer safety as a huge issue. The law will need to clarify responsibilities, probably through case law. Intellectual property will also become a battlefield. Designs and copyrights of physical objects can be very difficult subjects before you get to 3D printing. The book runs through some of the basic issues around 3D printing and IP law, including an introduction to Open Source Hardware, but without much detail. UK based printing aficionados should remember that the IP regime here can be very different to the USA. A more detailed analysis of there legal implications from a UK perspective can be found here.

Google Glass: just because you can…

Paul Bernal weighs out the privacy implications that are set to arise from the new Google Glass creation.

As a bit of a geek, and a some-time game player, it’s hard not to like the look of Google Glass. Sure, it makes you look a little dorky in its current incarnation, but people like me are used to looking dorky, and don’t really care that much about it. What it does, however, is cool, and cool in a big way. We get heads-up displays that would have been unimaginable even a few years ago, a chance to feel like Arnie in the Terminator, with the information about everything we can see immediately available. It’s cool – in a dorky, sci-fi kind of way, and for those of us brought up on a diet of SF it’s close to irresistible.

And yet, there’s something in the back of my mind – well, OK, pretty close to the front of my mind now – that says that we should be thinking twice about pushing forward with developments like this. Just because we can make something as cool as Google Glass, doesn’t mean that we should make it. There are implications to developments like this, and risks attached to it, both direct and indirect.

Risks to the wearer’s privacy

First we need to be clear what Google Glass does – and how it’s intended to be used. The idea is that the little camera on the headset essentially ‘sees’ what you see. It then analyses what it can see, and provides the information about what you see – or information related to it. In one of the promotional videos for it, for example, as the wearer looks at a subway station, the Glass alerts the wearer to the fact that there’s a delay on the subway, so he’d better walk. Then he looks at a poster for a concert – it analyses the poster, then links directly to a ticket agency that lets him buy a ticket for the concert.

Cool? Sure, but think about what’s going on in the background – because there’s a lot. First of all, and almost without saying, the Google Glass headset is tracking the wearer: what we can ‘geolocation’. It knows exactly where you are, whenever you’re using it. There are implications to that – I’ve written about them before – and this is yet another step towards making geolocation the ‘norm’. The idea is that Google (and others) want to know exactly where you are at all times – and of course that means that others could find out, whether for good purposes or bad.

Secondly, it means that Google are able to analyse what you are looking at – and profile you, with huge accuracy, in the real world, the way to a certain extent they already do in the online world. And, again, if Google can profile you, others can get access to that profile – either through legal means or illegal. You might have consented to giving others access, in one of those long Terms and Conditions documents you scrolled down without reading and clicked ‘OK’ to. The government might ask Google for access to your feed, in the course of some investigation or other. A hacker might even hack into your system to take a look…

…and this last risk, the risk of hacking, is a very real one. Weaknesses in Google Glass have already surfaced. As the Guardian reported a few days ago:

“Augmented reality glasses could be compromised by a hacker who would be able to see and hear everything the wearer does”

This particular weakness may or may not turn out to be a real risk – but the potential is there. Where data exists, and where systems exist, they are hackable – Google Glass, by its nature, could be a clear target. And what they get, as a result, could be seriously dangerous and damaging.

Risks to others’ privacy

Equally worrying are the risks to those the wearer looks at. There are specific risks – anyone who knows about the concept of ‘creepshots’ – surreptitiously taken photographs, usually of young women and girls, up skirts, down blouses etc, posted on the internet – should be see the possibilities immediately. As Gizmodo put it:

“Once these things stop being a rich-guy novelty and start actually hitting the streets, the rise in creepshots is going to be worse than any we’ve ever seen before”

They’re right – and the makers of Google Glass should be aware of the possibilities. Some people are even working on developing an app to allow you to take a picture using Google Glass just by winking, which would extend the possibilities of creepshots one creepy step forward – at the moment, at least, voice commands are needed to take shots, alerting the victim, but with winking or other surreptitious command systems even that protection would be gone.

Creepshots are just one extreme – the other opportunities for invasions of privacy are huge. In mitigation, some say ‘Oh, at least you can see that people are wearing Google Glass, so you know they’re filming you’. Well, yes, but there are lots of problems with that. Firstly, should we really need to check the glasses of everyone who can see us? Secondly, this is just the first generation of Google Glass. What will the next one look like? Cooler, less like something out of Star Trek? And the technology could be used in ways that are much less obvious – hack and disguise your own Google Glass and make it look like a pair of ordinary sunglasses? Not hard for a hacker. They’ll be available on the net within a pretty short time.

Normalising surveillance

All these, however, are just details. The real risk is at a much higher level – but it may be a danger that’s already been discounted. It’s the risk that our society goes down a route where surveillance is the norm. Where we expect to be filmed, to have our every movement, our every action, our every word followed, analysed, compiled, and aggregated for the service of companies that want to make money out of us and governments that want to control us. Sure, Google Glass is cool, and sure it does some really cool stuff, but is it really worth that?

Now there may be ways to mitigate all these risks, and there may be ways that we can find to help overcome some of the issues. I’d like it to be so, because I love the coolness of the technology. Right now, though, I’m not convinced that we have – or even that we necessarily will be able to. It means, for me, I think we need to remember that just because we can do things like this, it doesn’t mean that we should.

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.