The brewing war on some shapes

Wendy M. Grossman delves into the challenges that 3D printing is set to bring to individuals as well as governments, and what needs to be considered in order to offer protection to the masses.

It's about time we had a new new-technology panic, and here it is. This week the US State Department invoked the International Traffic in Arms Regulations to demand the removal of design files for "The Liberator" gun from Defense Distributed's "island of misfit objects", Defcad.

Defcad started up in the summer of 2012 when Makerbot, the owner of the 3D printing design-sharing site Thingiverse, refused to host designs for firearms. Those who know Net history will see a parallel here to early Usenet, when the relatively small group who ran things refused to create rec.drugs and talk.drugs. Frustrated, Gorden Moffett, John Gilmore, and Brian Reid routed around the decision and created the alt hierarchy, and with it alt.drugs, alt.sex, and, for symmetry, alt.rock-n-roll, setting the tone for Internet defiance of centralized control. This episode was followed by such incidents as the many mirror sites set up to host Scientology secrets in 1995 and the so-called Streisand effect. And yet it still seems not to have landed. By the time the US State Department acted, the files had been downloaded 100,000 times, and they're now readily available on your favorite torrent site.

Society at large is not in any imminent danger from these downloads, certainly compared to the millions of (metal) guns sold in the US each year: it's the sort of thing people grab because they *can*, out of curiosity. Few have the resources to really use the files. See for example Philip Bump, who recounts in The Atlantic the impossibility of actually getting the thing printed. The Guardian's Charles Arthur writes that specialists approached by British newspapers refused to print the design for safety reasons. Obviously it's not making plastic guns that's the issue; it's how to control who has them. This is the source of the panic, and the danger isn't the gun but the bad law people make when in that state of mind, particularly in the light of recent terrorist attacks.

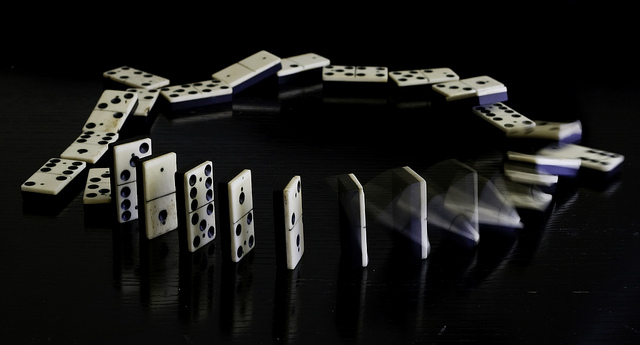

The early proponents of 3D printing specifically, and additive manufacturing more generally, hope it will eliminate some transportation costs, use materials more efficiently, create utterly new possibilities, and enable customization. In their recent book, Fabricated, Cornell researcher Hod Lipson and technology analyst Melba Kurman talk about the three stages they believe 3D manufacturing will go through:

First we will gain control over the shape of physical things. Then we will gain new levels of control over their composition, the materials they're made of. Finally, we will gain control over the behavior of physical things.

Under the influence of Lipson and Kurman, the world is on the verge of becoming infinitely malleable. They seem particularly entranced by the prospects for food printing customized to provide the healthiest possible diet for a particular genotype and lifestyle and living human tissue. The Defcad launch video linked above, however, has a different set of excitements: the democratization of manufacturing items previously controlled by regulation or copyright, much as the Internet did to digital content. Per the video, the site's goal is making an "unblockable open-source search engine for all 3D-printed parts", bypassing industry and government to make "the important things" like "medical devices, drugs, goods, guns".This is the 2013 physical world equivalent of Timothy May's Crypto Anarchist Manifesto. (Except, of course, that faced with a government threat the site promptly voided its video promise of "No takedowns - ever".

I've long thought that the first phase, now rushing at us, would recapitulate, far less pleasantly, the copyright and content wars of the last 20 years of the Internet's development. When the Defcad link came up for discussion among a few members of the Open Rights Group advisory council, I said as much. Certainly, the market and uses are growing fast. Alan Cox, who has posted some thoughts on this particular issue, calls this takedown the beginning of "the unavoidable collision between speech and physical objects", had a different take.

Cox felt there were four areas government should think about: trademark enforcement, regulation to protect people in shared environments (such as roadways; never mind thoroughly tested self-driving cars; what about the guy who's printed a wheel?); health and safety education for maker communities; and the recyclability of materials. "I would be far more concerned about the number of people who end up injuring themselves on badly designed home 3D printed objects," he concluded. This all makes sense to me.

But the bigger thing governments should think about is what can sensibly be regulated, and for that they must first free their minds of thinking they know what *things* look like. In that discussion, Cox called guns "irrelevant and old-fashioned". The key change brought by 3D printing and other additive manufacturing technologies is that we are not limited to the constrained shapes of the past. They knew Defcad had firearms because Defcad said so. Criminals wouldn't be so helpful - and if we could reliably understand what a series of bits described we wouldn't be in so much trouble with respect to cybersecurity.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

'Digital' goods to be brought into the real world.

3D printing has risen to the surface of the technological agenda, with many individuals and organisations discrediting the technological advancements that have been made, and drawing light to the implications that will arise if such machinery were allowed to thrive. It has created a stir amongst those who hold the belief that 3D printing will ultimately destroy industry and create mass unemployment, and those who believe that 3D printing positively demonstrates the technological advancements that society has made. They proclaim that such technological advancements will only work to alter the way we conduct business, and not necessarily render human labour redundant.

Z-corp have constructively drawn attention to the positive effects that 3D printing will have upon national economies if the concept were to fully ignite and take off. Z-corp have suggested that 3D printing will not only increase business productivity and innovation, it will also improve communication, speed up up the time that it takes for a product to be available to the market, reduce development costs, and make it easier to win business over. In addition, 3D printing could potentially have the power to replenish economies, as start up companies will no longer be restricted by manufacturing costs, and can put a product in the market without having to make substantial financial investments. However, this new way of conducting business can ultimately alter the supply chain, and perhaps detract the need for human labour in industries.

The concept of 3D printing has alarmed many individuals who have expressed concern about the potential copy right infringements that may occur as a direct result of making 3D printing available to the public. It is feared that 3D printing will open a window for intellectual theft, for there will be no means of preventing individuals from duplicating work without reimbursing the original artist. It will facilitate the loss of earnings for individuals who currently stay protected by mass production. Overall, 3D printing explicitly hints at the fact that it will alter the manner in which manufacturing will take place, it will deprive artists of royalties, render the manufacturing industry obsolete, and create further dents in the unemployment statistics.

Furthermore, criticism has blanched from anti-gun campaigners who have expressed concern that 3D printing will herald an unprecedented amount of weapon ownership amongst citizens on a world wide scale, with no means of controlling the flow of gun ownership. The first 3D printed gun was successfully fired in the US; the body of the weapon was created using the 3D printer, with the rest of the required pieces were easily purchased from gun shops, without the need for a license. The main concern is how to monitor and restrict the number of people that possess the blue prints that construct the weapons. Once someone is in possession of the required information, it will be hard to monitor the flow of information in order to prevent people from creating weapons with the intention of wreaking havoc.

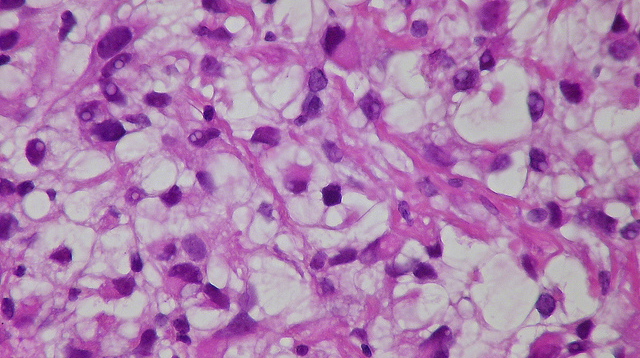

However, the NHS reports that there are currently over 10,000 individuals waiting for an organ donation in the UK. As our life expectancy steadily increases, so does our need for organ donations. There currently is a negative correlation between the demand and supply for organ donations, a trend which is likely to continue unless regenerative medicine can substitute the difference and revolutionise the medical realm. What irks most about the criticism that 3D printing has had to endure, is the fact that it can revolutionise the medical realm. 3D printers can help to create replacement tissue organs that are printed layer-upon-layer into three dimensional structures, which can be used to replace organs for those who are currently waiting for replacements. Perhaps such technological advancements should be celebrated for the positive changes that they bring to the table, and not be criticised for our inability to keep up with technology. It can have the potential to save lives.

Is 3D printing and new emerging technologies making the human race redundant and threatening the labour market or technology is simply creating new ways in which people work and interact? The problem seems to be that technology is developing at a faster rate than our ability to adapt to change; maybe we shouldn't be trying to slow technological advacements down, maybe we should try travelling at the same pace.

Image: Metastatic renal carcinoma, clear cell type Case 198 by Pulmonary Pathology CC BY-SA 2.0

Policy Jam

Wendy M Grossman examines the lengthy process of policy creation, and the ways in which technology can help to reshape and shorten the process.

There are two ways to approach fixing a complex system that everyone is unhappy with. One is to analyze the problem by asking what a fix would look like and then how to implement it. The other is to look at new technologies and ask how they can help.

In the case of government policy-making, the complaints are well-known and of long standing; they boil down essentially to the fact that policy is made by the few for the many, and there are always going to be disconnects in the interface between those two groups. The few may ignore, not understand, or not hear expert advice; the people most affected may not have a voice; entrenched prejudice may prove impossible to shake; the political climate may mean certain ideas simply will not be considered; or the resulting legislation may be derailed at the last minute by special interests. These difficulties are likely to remain no matter what mechanism you use for enacting legislation and no matter how you gather information and opinion beforehand. And the people don't always know best: in California, where the number of referendums turns the published voter instructions into something the size of a telephone book, popular policies may have adverse consequences that persist for decades after they become law.

The technology world has a weird and uneasy relationship with all this. Policy making is slow, which techies tend to hate. It's *governmental*, which libertarian techies tend to hate even more. Young upstarts simply ignore it by routing around it: the release of PGP onto the Internet in 1991, for example, up-ended entrenched policies on encryption. It's almost a sign investors could use that a technology company has reached the dreaded maturity when instead of bypassing laws by deploying new technologies it starts sending delegations to legislatures and hiring lobbyists.

It was therefore interesting to listen to the civil servants assembled for yesterday's London tea camp chew over short presentations from various people attempting to make real change in how policy-making happens in Britain. This is a discussion that I'd missed until now but that is taking place in a number of venues and reflects a broader plan for civil service reform that includes improving policy-making.

Among the major questions raised yesterday is how to broaden the range of information and participants: today's model of publishing consultations, collecting and collating responses, and then publishing reports and draft legislation attracts only the most dedicated respondents who then risk being thought of as cranks if they say the same thing too often even if they're both expert and right.

This is Anthony Zacharzewski's focus; his organization, Demsoc, aims to broaden participation. Government policy, he said yesterday, "has to be based on the best possible information. There are far more sources of information out there than policy-makers use." One of the things he complained about is speed: "People don't want to wait four years to change policy. We have to find people in the networks where they are already having conversations. They won't come to us."

And yet: policy-making isn't a speed trial. Policy that is going to affect a nation for decades to come should be implemented deliberately, slowly, and after careful thought.

Hannah Rutter, (Twitter: @openpolicyuk), from the Cabinet Office, struggles with the meaning of "open" in "open policy". "How to consult more widely is just one sliver," she said. "There's a broader piece about how to broaden the quality of the evidence we're getting - not just more academics and more think tanks - the people who are experiencing and delivering the services."

Other speakers are looking at how the civil service works, trying to use agile technologies to remake how policy is created, and running small, manageable experimental projects that can be shut down quickly and cheaply if they don't work. "If you're going to fail, fail fast," as Alice Newton (Twitter: @aliceenewton) put it.

That particular idea up-ends a characteristic of British government that the late Margaret Thatcher was especially keen on: policy begins at the center and propagates outward. The UK has no analogue to the US, where local government has its own revenue-raising powers and where therefore policies may start locally and then sweep the states before arriving at the federal level (data breach notification laws, for example, which started in California and worked eastward). Allowing the local authorities at the coal face to propose and test policies they want and let the successful ones percolate upwards would be a profound reversal of decades of increasing power at the center.

The more complex issue is harder to solve: how do you change the influence of money and promises of jobs that can sway and distort policy decisions, most notably but not solely in areas like copyright? It was the realization that policy-makers were simply not hearing the other side of the copyright debate that led Lawrence Lesssig to found a movement to counter that kind of influence. This is the problem open policy really has to tackle. Because: what politician will tell the nice man promising jobs in their local constituency to go away because a bunch of ragged-trousered posters on Twitter are opposed to the policy the nice man wants?

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of the earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are occasionally posted at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Namesakes

Wendy M. Grossman explores the continuation of domain wars that are currently a topic of discussion within Peru and Brazil.

The domain name wars are back: Brazil and Peru are objecting to Amazon.com's application to control .amazon. This sort of dispute has been going on for at least 20 years, and always, in my view, for the same reason: there is no consensus about what the domain name system is *for*. Various paradigms have been suggested over the last 30 years - directory, list of trademarks, geographic guide, free-for-all. There are cases to be made for all these ideas, by consumer advocates, lawyers, governments, or engineers (respectively), but the most current answer seems to be "a way for ICANN to make money". Set up in 1998, ICANN is the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the organization in charge of allocating Internet names.

I have a lot of sympathy with Peru's and Brazil's claim "Amazon" is a lot older than Jeff Bezos On the other hand, they already have the country codes .br and .pe respectively; it's not like they'll fall off the Internet without .amazon as well. But the lack of consensus about the purpose of the DNS (other than to ease human navigation) means these conflicts are inevitable. No clear structure guides who gets precedence: countries or companies, geographical regions or brand names.

The brief background: traffic is routed around the Internet by computers that use numbers - Internet Protocol addresses. To make it easier for humans, in 1983 Paul Mockapetris created the Domain Name System, which provides a server that takes the name you request and routes your request to the correct number. Domain names are hierarchical and read right to left in order of increasing specificity: google.com takes you to Google's main page, news.google.com takes you to the news servers at Google. The rightmost piece (.com in google.com) is known as the top-level domain, and these come in two types: generic (.com, .edu) and country code (.us, .uk). The intention was that national enterprises would register under their country code, and only multinational organizations would register under the handful of generic top-level domains (gTLDs): .edu (educational), .org (non-profits), .mil (military), .net (for staff of ISPs), and, of course, .com (for commercial organizations).

Blame the users that things did not work out that way. As things shook out, everyone wanted to be in .com, the gTLD that Mockapetris had originally opposed creating. As the early rush online grew into the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, people began complaining that all the "good names" were taken. By this they meant that the *meaningful* names in .com were taken. By 1997, plans were afoot to create more gTLDs and add support for international - that is, non-ASCII - alphabets.

Since then, a relatively small number of new gTLDs have been created with, it seems to me, relatively little effect. As of March 2013, there were more than three times as many registrations in .com as in the next seven gTLDs put together. It's also notable that the top three continue to be the oldies: .com, .net, and .org. What isn't so easily calibrated is the percentage of registrations that are defensive: IBM, for example, is registered in .biz, .info, and .org (plus, I'm sure, many country code domains as well), all of which divert to its main site at ibm.com.

In 2011, ICANN announced it would create as many as 1,000 new gTLDs via an application process that starts with a $185,000 fee and that closed to new entries in March 2012. Vetting the 1,900 applications ICANN received is understandably slow.

The absurdity of the whole situation is that what really matters are the numbers. You can, as the instructions for bypassing the UK court-ordered block on accessing The Pirate Bay show, get to a site using only its number (assuming you know it). Censorship efforts so far have focused on blocking access to a given site by altering the DNS server's response to requests for its name - a man-in-the-middle attack, basically. Yet few understand the numbers; it's the names that have meanings people care about.

Personally, I've never been convinced that the new gTLDs answer any real need. More, they revive and intensify all the old conflicts and confusions: under the old system you can have amazon.pe, amazon.us, and amazon.com and the "amazon" in each case can mean something different. Under the new one, only one usage can win. Kieren McCarthy, who has covered ICANN in greater detail than any other journalist I'm aware of and who even worked for the organization for a time, has raised a more frightening issue: that the Governmental Advisory Committee has demanded "safeguards" for the new gTLDs that, if implemented, could mean government-ordered content restrictions.

From the day ICANN was created, this potential for the organization to engage in censorship has been a frequently-voiced concern. So far, it has stuck to a narrow technical remit. But this year is seeing many more concerted efforts: the British Prime Minister is pitching for clean public wifi, and Eric Schmidt is imagining an Internet carved up by censorship into national regions. Whatever the DNS is for, it shouldn't be for implementing censorship. As Evgeny Morozov would despise me for saying: it would break the Internet as we know it.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted throughout the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Image: Amazon4 CIAT International Center for Tropical Agriculture CC BY-SA 2.0

Cautiously apocalyptic

"We've been waiting for societal readiness," Ian Danforth says, at the end of his list of factors that have kept us waiting for robots. The head of the pet-like prototype machine on the table next him nods.

Danforth is demonstrating the only actual robot at this year's at We Robot, which is otherwise mostly lawyers scoping out the legal challenges robots will bring. Danforth's video clip has it rolling around a little to chase a ball: I imagine becoming quickly bored (yes, yes, Aibo).

Yet Danforth confidently predicts that in six months "incredible, unexpected new robots you want in your home" will be available; in a year thousands of homes will have them; in two years tens of thousands; and five years will produce the first "true AI". We are less than a mile away from the research lab where John McCarthy labored for 50 years; in 1956 he thought it would take six months.

Danforth's ideas tap into a particular trend, which Ken Goldberg at UC Berkeley calls "cloud robotics". Today's networked computational power means that you can launch a cute pet robot into the market with rather limited abilities, and let it improve in the field via the cloud. People enjoy teaching pets tricks and find it endearing when they fail; why shouldn't this apply to robots? Coalescence happens for me when someone asks what kind of data this cute little pet will be collecting, especially in conjunction with other recent events. Answer: video, audio, accelerometer, and geolocation from an attached GPS unit, all sent to a central server, from where the data can be shared back out again so my robot suddenly knows a trick that yours has learned. Someone's actually implementing Rupert Sheldrake's morphic resonance.

Danforth claims the data will not be looked at by humans. Not impressed: as the ACLU's Jay Stanley has pointed out, what matters is less whether data is examined by humans or read by machines than the way the resulting decisions reverberate through the rest of our lives. Later, Danforth tells me the stream will be encrypted in transit to and from the server, and he hopes that if law enforcement issues a subpoena he'll be able to say he has no data to show them. Now, why does that make me want to say CALEA and communications data bill?

The notion of robot as intimate data collection device came up at the first We Robot last year, among the many other things lawyers worry about, like liability, but this is less hypothetical. It shows that Charlie Stross was right in his talk about the future of Moore's Law that computational power is yesterday's future, just as increasing transportation speeds were the future of the first half of the 20th century. Today's future is rapidly emerging as data (his meditations on the implications of bandwidth included lifelogging). Big data, open data, algorithmic decision-making. Asimov did not, if I remember correctly, consider this aspect of robotics. His robots fought through individual behavioral tangles brought upon them by the Three Laws, but did not collaborate across vast data networks and did not wrestle with deciding whether disclosing their intimate knowledge of you to a hostile interrogator would cause you sufficient harm that they should harm the interrogator or self-destruct rather than answer.

"Asimov's robots fought through individual behavioral tangles brought upon them by the Three Laws, but did not collaborate across vast data networks"

Julie Martin saw this as a possibly hopeful thing: "Robotics cases may force people to look at things they should be looking at," she said. "It shouldn't be different because it's robotics." She meant that the world is now full of data collection technologies we shouldn't be taking so casually, and robots provide an opportunity to make that visible enough to engage people in stopping it. In response, Ian Kerr commented that Ryan Calo has made similar comments about drones in the past – that they would spark a chance to h4ave and win a privacy debate that should have already taken place, "but I'm cautiously apocalyptic about that now".

One of Martin's examples was Tesla's recent spat with the New York Times, which showed how much data cars can collect about their drivers. Unfortunately, if the past discussions are any guide, the argument others will make is that in a world of CCTV cameras, wiretap-ready telephone services and ISPs, online profiling, and audit trails, "why should robotics be any different" will be the line used to justify the invasion of our most private settings. Cue Bill Steele's 1970s song The Walls Have Ears.

At this point an evil thought occurs: you sell a cute robot people will fall in love with. You include the kind of subscription service common in software, where you push updates and improvements to the robot automatically. Or, in the way of today's world, you offer those services free, contingent on my agreeing to data sharing. When I fail to resubscribe or refuse to provide data, all that stops. With an Internet service, the site stops giving me personalized service (search results, targeted ads). A pet robot would seem to stop loving me back. This seems to me a chilling but perfectly plausible business model and not at all what we imagine when we long for a robot to do the housecleaning.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series.

Image: Embodied AI's pet robot, by Wendy M. Grossman

Facts are Scared

Wendy Grossman gives some background to the call to open up the Postcode database, beginning with the question: Can you copyright facts?

There's a principle established in US law by the case Feist vs Rural Telephone Service Company that facts cannot be copyrighted. (Not that people don't try.) More than that, Feist established that a database of facts as basic as names, addresses, and telephone numbers compiled with little "sweat of the brow", cannot claim protection as intellectual property.

I hadn't heard of Feist in 1993, when the late Personal Computer World assigned a piece about the Postcode Address File (PAF)) and the telephone directory database, but the principle that information taxpayers pay to collect should belong to the public was apparently thoroughly embedded. I was shocked to learn that in Britain these databases were not only copyrighted, to the Post Office and British Telecom respectively, but that people had to pay to use them.

Twenty years later, Ofcom has just concluded a consultation to discuss PAF's licensing arrangements. The gist of its recommendations: that the Royal Mail simplify its pricing, but that it continue to "recover its costs" through licensing. The Open Data User Group begs to differ. Its response to the consultation objects to the redaction of costing details and questions the figures; suggests alternatives to PAF itself; ; and argues that PAF should become an open dataset free at the point of use in the public interest. ODUG also objects to Ofcom's "business-as-usual" tone.

ODUG's chair, Heather Savory, told the Guardian a few months ago: "This is data which comes from publicly funded, publicly owned bodies. The Royal Mail is very opaque about the costs and profits of keeping PAF up to date, but we're pretty sure they could afford to make it free."

Other than when you receive postal mail, the most common way you encounter PAF is that you fill out a Web address form by typing a postcode and choosing from a picklist of valid addresses. In the mid-1980s, software companies began licensing it to provide that functionality for over-the-phone sellers and direct marketers; by 1993 they were beginning to link PAF to other databases to create new applications. Jean Lemon, then the value-added resellers manager for the Post Office, told me about 15 licensees were authorized to sell software based on PAF; Ofcom's report says there are now 250 licensed "solution providers" who embed PAF in products from those familiar ecommerce applications to customer relationship management systems.

It's clear no one foresaw the data's many potential uses. Spokespeople for GB Address, one of those 15 1993 companies, told me: "When we started we thought there'd be a good market among mail order companies, but it turns out there's a big market among any companies collecting addresses: charities, travel companies, insurance companies, hospitals."

By 1996, I returned to the subject when a resident of the US state of Oregon paid a modest media charge to buy a copy of the state's vehicle licensing database and put the whole thing online. Cue discussions of privacy, the value of public data, and so on. The feature I wrote about that incident for the Daily Telegraph (TEXT) included an inevitable comparison to the situation in the UK, where getting a single address out of the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency requires you to fill out a form justifying why you need it and pay a (small) fee. So one reason something like "couldn't happen here" is that you can't get the data. This is how we get silly situations like requirements to click on data licenses on local council Web sites

At that point, the Royal Mail was barely beginning to think about the Internet. Lemon, revisited, told me that costs were coming down and the adding PAF to Internet application back ends didn't seem particularly difficult. She even raised the question of whether to continue to recover costs by selling licenses or to make the database freely available. Now, 17 years and three-four, Internet generations later, Ofcom is still dubious. .

Ofcom notes that although the £27 million PAF brought the Royal Mail in revenues in 2011/2012 is only 0.4 percent of its overall revenues, it's more than the £23 million the Royal Mail's operating profit that year. (Although: so what? What matters is how significant the roughly £2 million over operating costs PAF earns is to the Royal Mail's overall viability.) If, it argues, the Royal Mail absorbs the cost of maintaining PAF, then either the cost of postage will have to rise or the Royal Mail will have to be less profitable. But as ODUG points out, creating instead an Open National Address Dataset would benefit everyone while vastly lowering the costs the Royal Mail is claiming. The case for retaining "cost recovery" only makes sense if you consider Royal Mail's business in isolation.

If, however, we look at the Royal Mail as an element of the larger national economic system and an essential piece of the national instruacture, then keeping the data closed is absurd. Ofcom estimates the value of PAF to the British economy at £1 billion - 40 times the revenue it brings the Royal Mail. How much greater would the value to all of us if it were free?

Wendy M. Grossman's Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of all the earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted throughout the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

SilenceBreaker Media: recycling computers for disadvantaged communities

SilenceBreaker Media are developing a community focused multimedia hub to connect, inform and empower people via public access to technology. Jane Watkinson and Jay Baker talk about the debates thrown up by the discussion of net neutrality.

SilenceBreaker Media aim to reduce waste by collecting and rebuilding used computers for the benefit of disadvantaged communities – providing them with low-cost, ethical computers and training for them to get online, and get communicating using multimedia.

Key to achieving this is our adherence to the principles of net neutrality that are endemic within our projects and activities. Specifically, our unique focus is on the unequal supply of computer resources and teaching of relevant information and communications technology (ICT) skills in order to access and use the internet in the first place and how such supply does not match demand, especially in disadvantaged communities. Our projects involve participants learning how to physically rebuild a computer and install open source software, alongside gaining computer/internet related skills that participants can utilise to access the ever-increasing range of services and information computers and the internet provide.

Web 2.0, in particular, has connected communities and mobilised movements through sharing, cooperation, collaboration, and collectivism – something Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the World Wide Web, himself says was the whole point of the web in the first place. Social media has helped bring people together, transcending sex, race, class, and nationality, to exchange information – information that has been relatively free, open and easily accessible. But this is under threat.

The issue of net neutrality connects to wider debates regarding property rights and related socio-economic relations. Private property rights have been essential to capitalist development and accumulation. Given the growing importance of the internet and its potential for spreading democratic rights and free speech, the internet is increasingly being treated like another form of private property and a 'rightful' commodity of businesses and multinational organisations (e.g. Comcast), alongside some governments (e.g. 'Arab Spring') and intergovernmental organisations (e.g. ITU).

Often such parties see net neutrality as undermining free-market principles of efficiency and believe that net neutrality regulation – ensuring equality and non-discrimination of use – somehow undermines internet freedom. We can see from the recent ballooning of unemployment, debt, credit and asset bubbles alongside the increasing intensification and size of financial crashes and bailouts that the neoliberal model of 'self-sustainable' markets, privatisation and 'trickle-down' economics, this anti-net neutrality argument is based on, is facing a serious legitimacy crisis.

Thus, as with many things, the internet is under constant barrage of commercialisation and consumerist individualism. While net neutrality has become the key battle of the internet territory, social media has, too, been permeated and polluted by a culture dominated by monolithic multinational media corporations and as a result has often regressed into self-absorption, narcissism, and individualism, with profiles and status updates reduced to marketing campaigns for the individual wanting to look their best and have lots of 'friends'.

While this is not a problem exclusive to the internet, what perhaps might be is the open source movement, which is also being pummelled by right-wing libertarians perceiving free software not as opportunity for people power, but individual freedom over collectivism. There is a danger that such arguments can expose the internet to be viewed as a private property right that can then fall under the control by the few at the expense of the many. Access to the internet, as the UN and Berners-Lee have stated, is a human right and should not be undermined through corporate control, profit seeking or exploitation.

With post-war suburban sprawl, citizens turned into consumers, buying cars to travel home and television sets for in-house entertainment, impacting the appeal of the city centre's music halls, picture houses, and theatres. Concerns came as town footfall decreased and stores closed, and many people – from garage to car to parking space to workplace – didn't have to interact with neighbours or speak to many people at all, chatter provided by the radio. With the increasing prominence of the internet today, and the stereotype of the teenage blogger in their parents' basement, these concerns may seem familiar.

As digital downloads supersede the mountain of vinyl and plastic that filled the shelves of city centre stores, and once-unstoppable corporations like HMV and Blockbuster fall by the wayside, what will become of the high street? There may well not be much left for us beyond the suburban sprawl and its basements full of bloggers, a cruel punchline for net advocates. That is, unless we utilise the internet to connect people and put ideas, dialogue, and debate into action to contribute to a culture of communal areas, where people interact, go outside their homes in buildings they share with others, and stay in the cities for their daily entertainment of live music and art rather than the big screen back home providing 'messages from our sponsors' beamed directly into your ironically-named 'living' room. This is partly why SilenceBreaker Media are developing a community focused multimedia hub to connect, inform and empower people via public access to technology.

We can utilise technology to improve our localities, for the betterment of the population as a whole. That’s where our voices come in – and, again, technology can enable us to engage in diplomatic dialogue with those in power as never before. But there still needs to be the provision of resources and skills for the digitally excluded to do this.

For more on SilenceBreaker Media's net neutrality campaign watch our animation. For more detailed information regarding the campaign also check out our Net Neutrality campaign section on our website.

Has the German government’s Leistungsschutzrecht just protected the Internet by mistake?

Ed Paton-Williams reports on Germany’s new copyright law and how it might have accidentally done the Internet more good than harm.

German newspapers have been lobbying for a change to German copyright law for several years. They think that search engines and news aggregators like Google News threaten their businesses by reproducing their content without permission. Google News shows its users links to newspaper articles, a 240 character snippet of those articles.

Google argues that they’re increasing the amount of people who visit newspapers’ websites and see the adverts on those sites. Google doesn’t sell any adverts for its Google News pages. German newspaper groups, including Axel Springer - a News International-style corporation - think that Google and others should pay a licence fee if they want to put links and snippets of articles on sites like Google News.

Germany’s coalition government of Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the Liberals proposed in their 2009 coalition agreement to pass a law to “improve the protection of press products on the Internet.” They then introduced a Bill in November 2012 (often referred to as Leistungsschutzrecht or ancillary copyright) saying that websites would have to pay for a licence if they wanted to show links to or snippets of publishers’ copyrighted content just like the newspaper groups had asked for.

Internet advocacy groups like Digitale Gesellschaft ran campaigns against the Bill as did Google with its Defend Your Net campaign and Wikimedia Deutschland. Despite those campaigns and the opposition of the Social Democrats, the Greens and the Left Party, the German Parliament passed the Bill this morning. Victory for the newspaper publishers then. Actually, no.

There had been last-minute changes to the Bill which actually allowed websites to show short snippets of copyright text without paying a licence fee. Websites that want to use longer extracts or an entire article will still have to pay a fee. The Bill has done a complete about-turn and the German Parliament has in fact legislated to protect Google News’ model.

The easiest conclusion to draw is that the German government just hasn’t realised what it’s done. It’s legislated to allow Google and others to continue what they’re doing anyway. Even though their instincts seem to be to ensure that newspapers can continue with their current outdated business models, the German government has passed a law which may well ensure that newspapers have to change the way they make money.

Whether that’s what the German government intended or not, we should hope that the newspaper publishers dedicate their efforts to developing a business model that doesn’t rely on Governments passing laws that cripple the internet. Getting people to pay for the privilege of increasing another site’s traffic and advertising revenue just doesn’t make any sense and it discourages innovation. The newspapers should concentrate on doing some innovation themselves and work out how they can use the Internet to make money without charging those who want to link to their articles.

If the German newspaper industry wants to carry on pushing for licences for links and snippets then they’ll come up against dedicated opposition from Digitale Gesellschaft, Wikimedia and others again and again.

Ed Paton-Williams is a Campaigns Intern at Open Rights Group. He's interested in technology, politics and studied German at university which makes this pretty much the best possible topic for him. He blogs on British politics, gender and the politics of technology at edpw.wordpress.com

Image: CC-BY-NC-SA Flickr: dalbera

What went on in ORGZine in February?

February has whizzed by, so if you didn't have time to read all the zine articles, don't panic! This month's editorial highlights thus month's gems.

February's offerings were on a variety of subjects, from money to.. Scientology! Richard Hine gave us his opnion on the changing nature of 'news'; Guy Burgess discussed whether ad-blocking will become the next legal batleground; Nigel Waters talked about the future of privacy; Stefan Marsiske talked us through ParlTrack, a website which provides data about the European Parliament in an accesible format; Tobias Lauinger on one-click hosting and file-sharing; Rob Price on facial recognition; Ian Clark on what effect the worrying decline in record shops has on those who aren't online; and Mili Popova on digital colonialism.

February saw several interesting articles from Wendy M Grossman: on what we can learn from the cyber-attacks of the New York Times, on the encroachment on personal data security that allowing back doors for officials creates, on what we consider currency to be, and on Scientology's rocky relationship with the internet.

Looking forward to March in ORGZine:

As spring makes its first dainty steps, we'll be publishing a whole range of articles: members of SilenceBreaker Media discussing net neutrality and the importance of community; musings on ownership by Rick Valkfinge, founder of the first Pirate Party in Sweden; an article from a group called the English Disco Lovers who are using search engine optimisiation to reclaim some hated initials; an article on the rights and interests of game users.

Our new multimedia editor will be getting into the swing of things over the next few weeks, so keep your eyes peeled for Claudia's podcasts and videos!

If you’d like to write for us, or have an idea about what you’d like to read about, then we’d love to hear from you. Email Danya at orgzine.editor@openrightsgroup.org

Any thoughts anbout the articles? If you have anything you want to add, please feel free to comment, you may get an answer from the article's author!

What would you like to read about in ORGZine? Leave a comment below!

Widening the digital divide, one record shop at a time..

"Shouldn’t we ensure that, as we move towards an all-encompassing digital age, no-one is left behind?" Ian Clark looks at the issues thrown up by the demise of HMV.

The recent woes facing entertainment chain HMV played out some fairly familiar themes. A retailer that had failed to keep up with the shift by consumers to online shopping as a means to consume and purchase merchandise had found itself in financial difficulties, no longer able to keep up with the demands and expectations of its traditional customer base. The HMV story is not new or revelatory, and it certainly won’t be the last such example of a retailer struggling to compete with changing habits.

However, the reactions to its (not so sudden) demise were interesting. It was interesting to note, for example, the outpouring of nostalgia for the chain. HMV appeared to be viewed as an important cultural institution that occupied a special place in all of our hearts. Certainly, the famous symbol of HMV has become synonymous with the music industry in the UK, and it is hard to imagine the image of Nipper and his master’s gramophone being consigned to the history books. And yet, this nostalgia was for a multinational corporation. And, it’s worth reminding ourselves, a multinational corporation that, despite the nostalgia, has hardly been a benign force on the high street, having previously faced questions about its profits from CD sales.

The combination of the growth of HMV, the incursion by supermarkets and the emergence of the internet have had a significant impact upon independent record stores, resulting in substantial closures as they struggled to compete. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of independent record stores fell from 700 to under 300. For these stores (and, arguably, for the consumer) the competition from these three forces were a substantial threat to a diverse and vibrant retailing environment. It’s hard to imagine any of those who have been affected by this combined assault on their business being particularly sympathetic if there is one fewer force to contend with. Indeed, it has been suggested that the demise of HMV would actually be a good thing as far as the independents are concerned. The owner of Rough Trade, Geoff Travis, has already suggested that his company may look to expand in the light of HMV’s demise. Indeed, prior to HMV’s current woes, there were already signs that independents were starting to make a comeback. Given the growth in movements opposed to globalisation and multinational corporations (see the rise of the Occupy movement and the impact of UK Uncut), is it really a bad thing if a large chain falls and opens up opportunities for smaller independents? Would we be equally distressed if Tesco were to suffer a similar fate?

The combination of the growth of HMV, the incursion by supermarkets and the emergence of the internet have had a significant impact upon independent record stores, resulting in substantial closures as they struggled to compete. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of independent record stores fell from 700 to under 300. For these stores (and, arguably, for the consumer) the competition from these three forces were a substantial threat to a diverse and vibrant retailing environment. It’s hard to imagine any of those who have been affected by this combined assault on their business being particularly sympathetic if there is one fewer force to contend with. Indeed, it has been suggested that the demise of HMV would actually be a good thing as far as the independents are concerned. The owner of Rough Trade, Geoff Travis, has already suggested that his company may look to expand in the light of HMV’s demise. Indeed, prior to HMV’s current woes, there were already signs that independents were starting to make a comeback. Given the growth in movements opposed to globalisation and multinational corporations (see the rise of the Occupy movement and the impact of UK Uncut), is it really a bad thing if a large chain falls and opens up opportunities for smaller independents? Would we be equally distressed if Tesco were to suffer a similar fate?

Aside from competition on the high street, the demise opens up a lot of questions regarding the direction the digital age is taking us. The foundation of a capitalist economy is, ostensibly, choice. If consumers prefer a particular retailer over a competitor, the competitor will either need to seriously revisit its business model, or face inevitable extinction. Competition, we are told, benefits the consumer as businesses engage in a struggle to grow their business. Where companies fail to attract sufficient customers (or fail to encourage existing customers to spend more in their store) they fail. Consequently, should sufficient numbers of customers take their business to online retailers rather than the high street, high street retailers will fail. This is particularly a concern as consumers move from the high street to online retailers. However, this then leaves the question, what about those who use that service and have no alternative available to them?

The combination of a decline in independent record stores, entertainment retailers in general and HMV poses a real problem for some film and music lovers. Whilst many of us enjoy the benefits of internet access in our own homes, enabling a wealth of options for purchasing CDs and DVDs (not to mention streaming services and downloads of course) there are a great deal many others who do not have this luxury. For those that do not have home internet access (nearly 8 million people have never used the internet, let alone have a connection at home), the high street is their only viable option. The dearth of independents and the potential loss of HMV outlets leave many with a very restricted choice. For some, supermarket chains will be the only option left open to them. And, as we know, supermarkets are not in the business of providing a broad range, catering to every niche interest. They are only interested in items that will sell, ie populist titles, predominantly because they are already offered as loss leaders. Whilst there is nothing wrong with a focus on populist titles, there is something troubling about the way the market is heading. Those at the upper end of the economic spectrum will have a broad range of music and film available to them at the click of a mouse, whether by download or traditional physical formats. Those at the lower end, on the other hand, will be restricted to a small handful of populist titles. The free market is, effectively, patronising those on the wrong side of the economic divide.

The combination of a decline in independent record stores, entertainment retailers in general and HMV poses a real problem for some film and music lovers. Whilst many of us enjoy the benefits of internet access in our own homes, enabling a wealth of options for purchasing CDs and DVDs (not to mention streaming services and downloads of course) there are a great deal many others who do not have this luxury. For those that do not have home internet access (nearly 8 million people have never used the internet, let alone have a connection at home), the high street is their only viable option. The dearth of independents and the potential loss of HMV outlets leave many with a very restricted choice. For some, supermarket chains will be the only option left open to them. And, as we know, supermarkets are not in the business of providing a broad range, catering to every niche interest. They are only interested in items that will sell, ie populist titles, predominantly because they are already offered as loss leaders. Whilst there is nothing wrong with a focus on populist titles, there is something troubling about the way the market is heading. Those at the upper end of the economic spectrum will have a broad range of music and film available to them at the click of a mouse, whether by download or traditional physical formats. Those at the lower end, on the other hand, will be restricted to a small handful of populist titles. The free market is, effectively, patronising those on the wrong side of the economic divide.

This societal change pushed by the majority, by these market forces, risks isolating and excluding further a substantial section of our society. Consequently, could it be argued that we are moving towards a digital era which we as a society are not yet fully equipped to embrace? Shouldn’t we ensure that, as we move towards an all-encompassing digital age, no-one is left behind? Do market forces harden and entrench social divides, allowing the behaviours of the majority to take precedence over the needs of the community as a whole? Instead of rushing forwards into this new digital era in the name of ‘progress’ and ‘competitiveness’, shouldn’t we resist the forces of the market so that we can all progress together? Are we really ready for the digital age we have entered? From the point of view of the near eight million people who have never accessed the internet in this country, probably not.

This societal change pushed by the majority, by these market forces, risks isolating and excluding further a substantial section of our society. Consequently, could it be argued that we are moving towards a digital era which we as a society are not yet fully equipped to embrace? Shouldn’t we ensure that, as we move towards an all-encompassing digital age, no-one is left behind? Do market forces harden and entrench social divides, allowing the behaviours of the majority to take precedence over the needs of the community as a whole? Instead of rushing forwards into this new digital era in the name of ‘progress’ and ‘competitiveness’, shouldn’t we resist the forces of the market so that we can all progress together? Are we really ready for the digital age we have entered? From the point of view of the near eight million people who have never accessed the internet in this country, probably not.

You can read more articles by Ian Clark on his blog Infoism and follow him on twitter @ or follow Infoism @infoism

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.