Censoring Computer Games

Calum Grant looks at the history of video game censorship.

Censorship is a funny thing. When the likes of Pong, Pacman and Tetris were initially making waves, few people could have anticipated the regulatory laws, fines and prosecutions that were to be instituted over pixelated images bouncing around computer screens. But like all new technology - be it the internet, the printing press or even electricity - once the novelty had worn off and people became aware of what new possibilities were being opened up, governmental control measures were accordingly introduced.

After Michael Faraday had discovered how to create electrical power through mechanical means he was asked by William Gladstone, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, about the practical applications of this newfangled electricity. He replied that while he wasn't precisely sure what they would be, but was sure the government would inevitably find a way to tax them. Not only are computer games taxed in the UK, but their content is subject to legislative control. What is and isn't a suitable virtual task or setting for the citizens of this country is decided upon by a group of people who really aren't players of such games, let alone at the cutting edge of what is out there. It wasn't at the behest of several experts or various special interest groups that brought censorship to the games industry. Indeed, what ultimately instigated rating systems and the means to ban games was calls from the national press, in a chilling example of how few vocal objectors are needed to curb freedom for everyone in the United Kingdom.

The aforementioned games came into being in the late 1970's and early 80's, but over the course of following decades technological progress has allowed games consoles to establish their presence in the homes of more and more houses in the western world. Two dimensional platform-based digital adventures were all the rage, and were marketed specifically towards children. This salient fact is often overlooked, that this new technology which utilised the improving processor speed of computers was first being used as a new range of children's toys. Rather than this new gadget being confined to the tinkering hands of the wealthy, the experts or the posers, it found its way into the little hands of a curious and captivated generation.

Unfortunately, it was also this novel aspect which brought about calls from the tabloid press to introduce regulatory standards akin to those used for film. The violent nature of games like Mortal Kombat, in which players street fight to the death, served as lightening conductors for the sparks of misinformed 'save the children' like calls to fall upon. That was the early 90's, and to look at these games now and see the poor and crude graphics they employed makes one wonder how they ever caused anyone to bat an eyelid, let alone compel them to call for the introduction of legislation.

Nevertheless, the UK games publisher trade body relented and created several age cut-offs customers would have to meet in order to legitimately purchase them. In spite of this, games with violence towards people or animals, and/or the inclusion of sexual content had to be submitted to the BBFC, the body whose primary responsibility is the age rating and censorship of motion picture films. In a somewhat comical turn of events it later transpired that the 'Video Recordings Act' which they used to prosecute retailers for selling games to minor was technically unenforceable due to a technical error during the passing of the bill. This strange anomaly was discovered while civil servants were researching the bill was was to supersede it in 2009, meaning for a time those supplying any violent and sexy games to children could not be lawfully be prosecuted. Unfortunately this golden age was short lived, as the blunder was soon corrected.

The first game ever to be effectively banned in the UK was the late '90s title 'Carmageddon' in which the gamer roams the streets in a car running down pedestrians. Though not banned per se, it was denied a rating classification making it technically unsellable. The games producers, presumably anticipating such action, already had an alternative version of the game in which the humans on the pavements were replaced with green blooded zombies. When resubmitting this version of the game to the censure board it passed with flying colours especially green. Such creatures didn't give rise to the same qualms and it was given an 18 certificate.

Players of one of the biggest game franchises in existence 'Grand Theft Auto' will perhaps be dumbstruck to learn of this ruling, given that the GTA games allow the player to run down, shoot and beat up the virtual innocents bystanders in the game to their hearts content. It is thanks to games like Carmageddon that enough ground was broken for misanthropes everywhere to have an outlet for their tendencies to be unleashed without actually harming everyone. Some might argue they are harming themselves, but the incidence of lone sociopathic killers reeking death on Britain's streets has not yet reached a level to be noticeable by the same press who are quick to condone the dangers they allege such game to have.

Indeed, I recall that one of my school teachers wasn't sure whether one of the Grand Theft Auto titles was suitable for his son. Rather than going on other opinions, however, he decided to simply rent the game and play it. In doing this he was allowing himself to make the most informed decision possible about what he considered permissible and acceptable for his son to play. The result? After the rental time had elapsed he immediately bought the game to sate the compelling desire to keep playing the game to completion, often appealing to my class for advice on how to successfully carry out various tasks within the game. The son had to wait for his old man to finish before he even had a chance to play.

As charming as that story is, it's certainly not possible to put such a method into practice for every game, film, book, website, etc. their child would like to see, and so content warning of certain aspects present in games is hard to argue against. On the other hand the outright ban of a computer game for all adults only serves to raise the profile and carry out the games marketing for them.

For example, when the brutal killing of one teenager by another occurred in 2004 an again outraged press asserted that the game 'Manhunt' was causal factor in bringing about the savage murder. The game is undeniably violent, but the context of the plot and the fact that it was markets for an adult audience should not have been so easily forgotten. The gamer inhabits a protagonist who has been kidnapped and has woken up in a compound which is used to make snuff films (movies which depict the killing of people). The plot of the game is trying to escape the facility without getting caught and in turn killing many of the evil men trying to kill you in full view of the cameras everywhere. Various sectors of the press then alleged, off the back of comments made by the victims family, that the young killer had played this game obsessively in the weeks leading up to the murder. However, in a bizarre turn, it transpired to be exactly the other way around that the victim had played the game extensively while the killer had never laid hands on it.

Nevertheless the damage was done. In response to mounting pressure from the press, major game retailers refused to sell Manhunt. This ultimately drove up sales of the game overall. Recognising the effect such publicity had on sales, the producers behind manhunt were sure not to tone down the levels of violence for the sequel resulting in it being banned before its release in the UK.

What emerges from these scenarios is a familiar response, and video games frequently come up against this reaction from the more reactionary elements of the new media. It is very easy to generate shocking headlines and articles of groundless drivel about how violent games are and the fallout it must be wreaking, but this has culminated in regulations which lead to some quite bizarre rulings. Why should it not be okay to assassinate mercenaries hired by a rich sadist in one game but fine to kill green blooded fellow who, for all we know, mean us no harm at all? It seems that trying to take a moral position on what is permissible in the world of pixels is doomed to give rise to such farcical situations, and ultimately fail in its intent.

The viewing of films, on the other hand, is widespread. They are deemed to be a world apart in terms of cultural significance and ethical worth when compared to computer games. More importantly, the people who make such rulings on films have usually spent a lifetime watching and appreciating them. Gaming is unfortunately still perceived to be a juvenile past time, and the generation gap between those playing the games and those deciding what is legal to play is what is resulting in a more patriarchal relationship between censors and gamers.

Calum Grant is a freelance writer based in London. He has a background in physics and biology research, and science and mathematics teaching. You can find his website here.

As such

Wendy M. Grossman looks at the changes in patent law in New Zealand.

There was a brief but heady moment last week when we all read the headline New Zealand band software patents and thought: Wow.

That lasted a couple of hours, until I read Florian Mueller's FOSS Patents blog, which explains why that emphatically did not happen. Instead, he argues, whether there's a genuine ban or not will hinge on how the law is interpreted by the courts and the patent office: "…the courts and the patent office in New Zealand still have massive wiggle room to allow software patents." In a follow-up post, he provides a lot more detail behind his thinking, of which the most interesting part is his discussion of what kind of law would have been a clear ban. (In one of those you-couldn't-make-this-up details, I note that the Commerce Minister in charge of the bill is named Craig Foss. How utterly perfect.)

Mueller also points to two other assessments that largely agree with his: Techdirt, which calls the law "a worthwhile experiment to monitor", and Intellectual Asset Management, which says the range of what can be patented has only slightly narrowed and that the New Zealand courts will rely on UK case law for guidance. Since the UK has granted and continues to grant plenty of patents on software, it seems clear that these three experts are right: software will continue to be patented in New Zealand, just possibly not quite as easily as before.

Silicon Beat helpfully points to the relevant clause:

(1)A computer program is not an invention and not a manner of manufacture for the purposes of this Act. (2) Subsection(1) prevents anything from being an invention or a manner of manufacture for the purposes of this Act only to the extent that a claim in a patent or an application relates to a computer program as such.

(3) A claim in a patent or an application relates to a computer program as such if the actual contribution made by the alleged invention lies solely in it being a computer program.

It all hinges on that "As such" - clarity only a lawyer could love.

Mueller argues that the widespread overreaction in the mainstream media has to do with the fact that patent law is poorly understood by anyone who's not an expert. That's fair, especially when coupled with the pressure to churn out stories. I suspect, though, that the reaction also reflects the pent-up frustration among many both inside and outside the industry who see software patents as a hindrance rather than the economic booster they're intended to be. See for example the Washington Post's Timothy B. Lee asking with real yearning why the US can't follow suit, citing a new General Audit Office report that highlights the particular problems with software patents.

For a long time now, the software patents have seemed like a big game of Chicken: plenty of people say they want to rein the patent system back in -- but no one's willing to be the first to lay down the application forms. I saw this in action back in 2004 at a Berkeley, California discussion of patent reform that pulled in lawyers from the heart of Silicon Valley.

My favorite quote, from a patent lawyer in a large Silicon Valley company who wanted everyone to end the arms race by simply agreeing to stop:

You can tell the system isn't working when engineers don't respect it. And they don't. They see patents being awarded to people they consider not as smart as they are for work they think is mediocre, and they think it's a game. It should be an honor to be granted a patent. We should raise the bar." Unlike a lot of people, he didn't, however, think it was necessary to get rid of software patents or even, necessarily the ultra-controversial patents on business methods. "We need to get rid of bad patents."

Judging from the preamble to the published versions of the bill the legislative effort started with the intention of tightening the law on what may be patented in order to bring it into line with other countries: "This low threshold can lead to broader patent rights being granted in New Zealand than in other countries, which can disadvantage New Zealand businesses and consumers, as technology that may be freely available in other countries can be covered by patents in New Zealand. This can discourage innovation and inhibit growth in productivity and exports." While it's refreshing to see *any* government recognize that intellectual property regimes can inhibit innovation as well as encourage it, harmonizing, rather the ground-breaking, was clearly the intent.

So, sadly, we're still in that giant game of Chicken. If the US wants to abolish software patents it's going to have to do so as a ground-breaker. And it's always hard to be the guy who puts down the weapons first. Yet there are hints that even the US is beginning to see the problem.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of the earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Image: New Zealand Pigeons on TV aerial; Silverstream, Upper Hutt by Lance Andrewes CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

First-World Problems

Wendy M. Grossman looks at the 'first-world' problems that the digital world is currently enduring.

A friend who for a while worked for a large company with offices all over the place used to recount the complaints he heard people make. Of which, my personal favorite was, "My twin 30-inch monitors are blocking my view of the mountains."

Closer to home, my actual neighbors take it personally when too many alien cars are parked on their street ("I don't want to have to see them" says one) and gripe about the noise of the planes from Heathrow (which in a different part of their brains they're glad is conveniently close for when they fly on vacation to Australia or Macau). It's the unselfconscious naturalness with which people use the word "nightmare" for their broken washing machine or the tiny dead pixel-sized flaw in the paint on their Jaguar E-type that makes entertainment out of the lack of perspective and arrogant ease of life in a country where one does not have to walk five miles to bring back water in a bucket.

Sometime in late 2008, when the recession was just beginning, I heard a Russian economist expounding on American radio the reasons why Americans would be unable to cope with a real economic depression, as opposed to Russians. Russians, he said, are used to living in small spaces with their extended families. Russians, he said, help each other. Russians, he said, are used to getting up and doing stuff for themselves instead of sitting around on couches watching TV. I thought he was full of garp. For one thing, Americans may be flung far from their relatives, but there is a strong local community culture built around friends and local interests, especially churches, that he was completely either ignoring or ignorant of.

In a case of real economic breakdown, I feel sure that neighbors with big lawns backing onto each other would gear up to share the space to grow vegetables and raise chickens and maybe a couple of goats. I have no trouble imagining older neighbors teaching skills like cooking, preserving, sewing, and wood and metal working to younger ones. And so on. It's not the life today in suburban Anywhere USA, but people do what they must to survive. Few people anywhere become couch potatoes because that's all they can do. They do it because they *can*, a very different situation. People change when circumstances change.

Conflating the US and UK somewhat here, this month has been a scary vista of circumstances changing. For years, privacy advocates have lamented the public's apparent lack of interest in privacy. Companies selling privacy-enhancing technologies have come and gone, from DigiCash to Canada's Zero Knowledge Systems to the lemming-like march to pay with personal data for "free" Internet services. The security services' reaction to the Snowden and Wikileaks revelations - the detention of Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald's partner, David Miranda, the raid on the Guardian, the treatment of Bradley Manning - suggests that either they believe the public really doesn't care or they want to intimidate us to make sure we don't dare to care. Bruce Schneier believes something close to the latter: he calls Miranda's detention poorly controlled anger, the most dangerous explanation of all, though he also thinks the real target was documents Miranda was carrying. At Slate, William Saletan calls the detenction an abuse of anti-terrorism law.

At a debate in July that I attended, Duncan Campbell - whose own work exposing the Zircon spy satellites got New Statesman and the Glasgow site of BBC Scotland raided in 1987 - argued, "The walls of secrecy have to come down. We are an adult society. We have learned that terrorists are among us." Later, referring to a comparison made by German premier Angela Merkel between PRISM and Tempora and the activities of the Stasi: "We have lost the memories of fear that are so fresh in Germany. Heaven forfend that we should have to go through these experiences again to learn why it matters. But there is a generation of hackers and snoopers who have forgotten that it matters." Instead, he said, "We can have more trust if we get these programs out in the open." What he's asking for is a complete cultural change in the security services, a tall order they are going overboard to resist - and yet, as Charlie Stross pointed out this week, it may be forced on them through generational change.

Separately, a friend wondered: if David Miranda had been Glenn Greenwald's heavily pregnant wife, rather than his husband, would it have been clearer to his detainers how the world would view their actions? Another asked, "Do they *want* to make more terrorists?"

Don't we all want easy, comfortable lives? Where secure email services like and Silent Circle can operate for those who, really need them - and where those people aren't us? Where the indefatigable volunteer owner of a hugely useful site like Groklaw doesn't feel she has to stop explicating the hard parts of patent law? Where a newspaper publishing controversially in the public interest might be taken to court, but not raided? Today these are first-world problems.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Image: Recession Art by tim rich and lesley katon CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Hamlet and the British Library

Milena Popova looks at whether or not the British library are just in their decision to deny online access to Shakespeare's Hamlet, because of its 'violent content'.

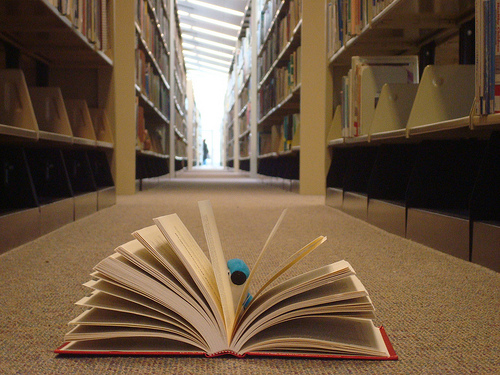

So this month author Mark Forsyth found out that the British Library blocks access to Hamlet on the grounds that it is violent. In pantheons across dimensions, the gods of irony collectively handed in their resignations. Of course, the pertinent question here is not why the institution charged with keeping a “comprehensive collection of books, manuscripts, periodicals, films and other recorded matter, whether printed or otherwise” should censor what is commonly considered one of the greatest works of English literature - I am going to take it as read that that’s frankly ridiculous. Rather, the pertinent question is what on earth is the British Library doing censoring anything in the first place? Therefore, I’d like to examine a few instances where a case might be made for a library of record censoring or restricting access to certain materials.

The curious case of back issues of the Sun

Among its many collections, the British Library takes pride in its newspaper section, which features pretty much every British and Irish newspaper published since 1840. One interesting feature of this collection is that it contains many images which under current legislation are defined as Level 1 indecent images of children. Prior to 2003, many models for Page 3 and similar features were aged 16 and 17. However the Sexual Offences Act 2003 extended the definition of “child” for the purposes of “indecent images of children” to include 16- and 17-year-olds, effectively consigning large chunks of back issues of The Sun to the category of “indecent images of children”. Possession and distribution of these is illegal. What should the British Library therefore do with it’s extensive collection of such images?

Mein Kampf

There is a popular belief that Hitler’s Mein Kampf is banned in Germany and Austria. Given the destruction that the ideas in that book unleashed on Europe and the world, one could even possibly understand a decision to ban it. The legal situation, however, is considerably more complex. Possession of the book for private use is legal in both countries. So is the sale of copies printed before April 1945. What is banned is the deliberate distribution of national socialist propaganda, including the import of new copies of the book. The reason no new editions of Mein Kampf in German have been published since 1945 is that the state of Bavaria holds the copyright to the book. That, however, expires in 2015, and there are significant concerns that neo-Nazi organisations will take the opportunity to republish Mein Kampf with their own slant on it. Should libraries in Germany and Austria therefore hold copies of the book? The answer is that they do. Libraries in both countries stock the book and allow use of it for research. There are also currently plans to publish a new, annotated edition, putting the work in an appropriate historical context. There is clearly a recognition here that the banning and censorship of ideas is not an effective method of combating them. A critical examination, on the other hand, enabled by the availability of the book in libraries and by a new annotated edition is much more likely to ensure history is not repeated.

Banned books through history

Of course banning great works of English (and other) literature is hardly unprecedented. The Canterbury Tales have been banned and censored on and off for centuries. At different times people have taken issue with different aspects of the work, from its criticism of the church, to sexual innuendo and depictions of rape. As recently as 1995, the book was removed from a the syllabus of a high school course in Illinois for its sexual content.

J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye was the most censored book in US high schools and libraries between 1961 and 1982. It continues to feature regularly in the American Library Association’s top ten list of most challenged books. The reasons for challenging the work include vulgar language, blasphemy, undermining family values, sexual references, and encouragement of rebellion. I know I certainly found the book deeply emotionally moving as a hormonal teenager and also that it didn’t hold its own upon a second reading as an adult. Neither of those, however are in my view valid reasons to ban it.

Shakespeare himself is no stranger to being banned, censored and bowdlerised. Reasons people have objected to his work should by now sound familiar: vulgarity, blasphemy, sexual references, references to suicide and sex work. Add to that “encouraging homosexuality” (Twelfth Night) and anti-Semitism (The Merchant of Venice).

Ultimately, our society and our moral values change. I don’t necessarily want to live in a society where eroticised images of 16-year-olds or Mein Kampf are considered good things. Having said that, I don’t think any of the people who have challenged and banned Shakespeare and Chaucer through the ages would want to live in our culture today. Many of the works banned, challenged and censored throughout history are now considered classics. There is no way for us to know what society will value in 50 or 100 or 300 years’ time.

More importantly, even works which we today consider harmful or illegal have value in that they help us understand the cultural and historical context of their time. The British Library Board is specifically charged with managing the Library as a “national centre for reference, study and bibliographical and other information services, in relation both to scientific and technological matters and to the humanities.” It is there to store, preserve and make available to the public and to researchers documents and artefacts of humanity: our culture, our history, our knowledge. As a library of record, the British Library in my view has an obligation to store even the most dubious of our cultural output. While a valid case may sometimes be made to restrict access to certain materials, this should always be on solid legal grounds, after thorough review, transparently and on a case-by-case basis. Blanket filtering of any work, let alone Hamlet, on grounds as spurious as “violent content”, is in no way consistent with the ethos of the institution.

Image: 2008-04-05 (London, Petrie and British Library) - 097 by Nic McPhee CC BY-SA 2.0

To filter, or not to filter...

Stephen McLeod asks, do the same rules of engagement apply with relation to the internet?

Remember the advice that adults used to give young people about using the Internet, back when it came from the mouths of 'experts' such as the illustrious Carol Vorderman?

'Never give out your real name online'

'Never give out your e-mail address to a stranger'

'Never send your photograph to anybody you don't know'

Whilst this advice seems laughable in the infinitely connected world of 2013 (well, to most of us anyway, this can still be found on some Government websites), it was just as ridiculous back then - especially to those of us who were the last generation to grow up without having the Internet wired into our everyday interactions. As we took to discovering the best ways to navigate this brave new digital frontier on ridiculous 28k dial-up modems, it was already clear that adults simply did not understand the way that things online worked.

Can you imagine the reaction from a parent 10 years ago, had their child had come running into the living room, exclaiming:

'Mum! Dad! Somebody said nasty things to me on the Internet.'?

Probably not.

For those of us who have been online for a long time, it can seem bizarrely naive that anybody would expect to come online and not expect to be the subject of any abuse. The culture of the Internet has long since been about stirring up reactions. Everywhere you look, users are playing devil's advocate; purposefully asking divisive questions; and criticising statements from every angle to such an extent that nobody can be sure whether anybody is actually being serious about anything anymore.

…and that's the beauty of it; the Internet is serious business after all. The architecture of the web, and the ability to be anonymous or employ multiple identities all at once forces us to confront the inconsistencies in our own positions; challenges how we react to others who disagree with us; and highlights hidden prejudices. It is the ultimate playground for deconstructivist postmodernism.

Young people who have discovered the deepest corners of the Internet long before their parents have had to confront all of this chaotic and often contradictory approach to the way people communicate purely off of their own backs. Many have had to subconsciously develop sophisticated ways of dealing with a medium which is complex and often aggressively confrontational. The relative ease of this process for these generations isn't something that we should be too surprised about. How many of you are aware of what it's actually like to be a high-school student in recent years? Some of the things said by teenagers in 'playgrounds' across the country would raise more shock and consternation than the tweets that increasingly garner outraged national media attention.

As the discussions in recent weeks have illustrated, those who are most vocal on these topics have still simply failed to understand the fundamental fact that the same old rules of engagement do not apply when it comes to the Internet - or at least, not with regards to their application. Just as we know and learn how to deal with the sliding scale of what is appropriate in 'real life' situations with people we find undesirable, we have to adapt to the environment of the Internet. Whilst there are undoubtedly threats that should be taken seriously, we must also recognise that not all messages which appear alarming are created equal, nor should warrant the same level of response. How we deal with abuse online will unquestionably require the law to respond to some degree (with all of the jurisdictional restrictions and complications which that brings), but it is necessarily eventually a social and cultural question rather than a legal one.

Instead of looking to implement restrictive legal remedies against the providers of platforms which allow the anonymous transmission or exchange of information, we must ensure that both ourselves and our young people are properly equipped to handle the realities of this world that they arguably know a lot more about than the majority of their seniors. We have to stop patronising them by making out that we know better than them about how to survive in every given difficult situation they will encounter, just as we don't interfere in every interaction they have whilst amongst their friends at school.

Let's also bear in mind just how contradictory the advice that's been given over the years about how to be safe online has actually been - moving from a position of keeping your identity anonymous as we've seen in the opening paragraphs, to one where instead now we are apparently actively calling for networks like Twitter to verify everybody against their real name and address so that we can find out who the perpetrators are… or... something.

The recent media flurry around the deaths of young people after receiving abusive anonymous messages on platforms such as Ask.FM has caused the oh-so-predictable misinformed knee-jerk reactions that have come to characterise what we might expect, and just reinforces to young folk again that adults really don't have a clue what they are talking about. What I haven't seen mentioned in a single one of the reports concerning the 'responsibility of online providers to prevent anonymous abuse on their systems' is the fact that users actively consent to questions from anonymous users. Tumblr does it. Ask.FM does it. Formspring.me does it. All of these services provide a simple way for people to avoid getting exactly the sort of messages that they are being charged with responsibility for.

In some places (such as Twitter) this might not be as easy a process as people who are high profile (and thus naturally receive a higher volume of interactions) may like, but this is certainly not the case when it comes to the likes of Ask.FM. Not only can you choose to never receive anonymous messages, but you also have an additional blacklist for specific users you might want to filter out. See this screenshot of their settings panel:

We must be careful not to confuse the issues of one circumstance with another.

The real question that we should be asking is not how to find a legal redress against networks (read: The entire Internet) for providing people with an anonymous way to communicate, but why when given the choice to opt out of interactions from people that don't identify themselves, people choose to continue to receive them… even when that includes abusive messages. The feature itself is often used so that people can send Valentines-esque messages in a secret admirer type fashion, and so in reality it often comes down to questions about insecurity, self-esteem, and how people want to be seen by others. Shouldn't we perhaps be concentrating on this instead, and how best to help our young folk deal with these sorts of issues, instead of leaving them to work it out on their own…?

Whatever the answer is, it isn't to point the finger of blame at the Internet.

Stephen Blythe is an internet law geek with an LLM on the way, and Digital Marketing Manager for tech firm Amor Group. You can find him on Twitter, and Google+.

Illustration by Nadine Khatib

Image: Illustration by Nadine Khatib

The bully season

Wendy M. Grossman looks how recent news headlines have exposed the different kinds of online bullying.

For much of this year I've been helping write and edit guides to coping with and preventing cyberbullying - the kind of thing, in fact, that has been cited as playing a role in the death by suicide of 14-year-old Hannah Smith. The upshot may be bullies on the brain, because this month they seem to be everywhere one looks. In escalating order:

Item: In one of those disputes that arises from time to time in the US because of the persistent battle over who should pay whom, customers of Time-Warner cable currently cannot view CBS or its affiliated channel, Showtime. For those in the UK, this is about equivalent to Virgin cable deciding to block ITV. It is as clear a demonstration of why network neutrality is about antitrust as one could wish. Time-Warner argues that it deserves more money for delivering the audience to CBS, a broadcaster and producer of content. CBS argues that if it didn't provide content, no one would subscribe to Time-Warner. To make its point, CBS is blocking Time-Warner cable Internet subscribers from accessing content on its Web sites. Caught in the middle are consumers, who continue to receive cable bills in the full amount for less than the service they're paying for. As Ken Levine wrote yesterday, We're all just pawns. The only winners are file-sharing sites. There can be no greater impetus for unauthorized downloading than a complete inability to access content for which you have legally paid.

Item: over at Knowledge Ecology International, James Love writes that Michael Froman, the US trade relations ambassador, wrote to the US International Trade Commission objecting to the injunction stopping Apple from violating a patent a court ruled belonged to Samsung. Groklaw has more on the way this particular patent dispute has turned into let's-play-national-favorites. Again, the pawns here are consumers, who care very little who wins as long as they can get smart phones that are easy and fun to use and who, though the prices attached to those phones, are paying for both sides of this dispute. Historically, Apple does better focusing on (insanely) great new ideas than it does in suing the old ones. But litigious behavior, too, is part of the legacy of Steve Jobs, who vowed to destroy Android because it was a "stolen product". That's Apple's excuse. And the US?

Item: I love online shopping probably more than the next person, but this Mother Jones article outlining the working conditions for those working in the warehouses of a company that could be Amazon.com and the Democracy Now follow-upgive me pause.

Item: In a particularly vicious kind of attack, a number of otherwise innocuous sites, including that of a furniture retailer, were hacked so that users following links from pornography sites would be taken there and infected with malware while being shown images of child sexual abuse. As Charles Arthur finds in the Guardian, the purpose of the images was simply to scare people into not getting their machines cleaned. A not unreasonable fear: arrests based on repair folks finding such material on people's machines have been known to happen. This is a vicious attack for all concerned: the businesses whose sites were hacked may find themselves on blacklists and the hacked individuals are at risk for both identity theft and the possession of illegal images.

Item: It's hard for me to imagine a more innocuous campaign than one to get Jane Austen's face onto a £10 note. And yet the successful outcome got Caroline Criado-Perez rape threats on Twitter. After some initial hesitation, the wheels of Twitter and the police cranked into gear and there have been arrests. Good: these threats were not just another misunderstood Twitter joke. And yet: with all the regulatory posturing David Cameron has been doing lately, we must be careful not to return to the days when it was common for media to warn women that the online world was too dangerous for them to handle. I was pointed this week at an excellent essay by Laura Miller from those days (unfortunately, not online: you must source a copy of the book Resisting the Virtual Life in order to read it) warning that characterizing cyberspace as the "frontier" and women and children as endangered is a narrative that inevitably leads to regulation. Criado-Perez didn't need new regulation to control Twitter or the police; she just needed them to *act*.

Item: A thirteen-year-old girl who was the victim of sexual abuse by a 41-year-old man also needed the justice system to act. And it did, up to point: it got the abuser arrested, prosecuted, and into court. At which point the whole thing broke down. The prosecutor described her as looking older than 13; the judge called her "predatory" and said she egged her abuser on. This is the nastiest, most profound, most personal kind of bullying because it comes from the very people who are supposed to be the ultimate repositories of society's trust. And it didn't happen online, it happened in real life. If David Cameron really wants to protect children, *this* is where he should start.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

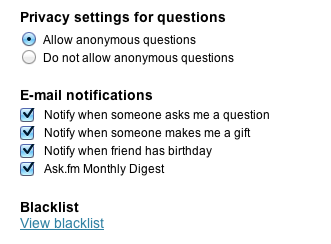

Nudging the public into censorship: The effect of default opt-in on decision making

Ben Meghreblian looks at how research into decision making can cast light on the government encouraging Internet users to have their Internet connections filtered by default.

Last year the Government decided that it wanted ISPs to “actively encourage parents...to switch on parental controls”. Two weeks ago the Department for Department for Culture, Media & Sport released a policy paper in which they said:

“Where children could be accessing the internet, we need good filters that are preselected to be on, and we need parents aware and engaged in the setting of those filters.” (pp. 36)

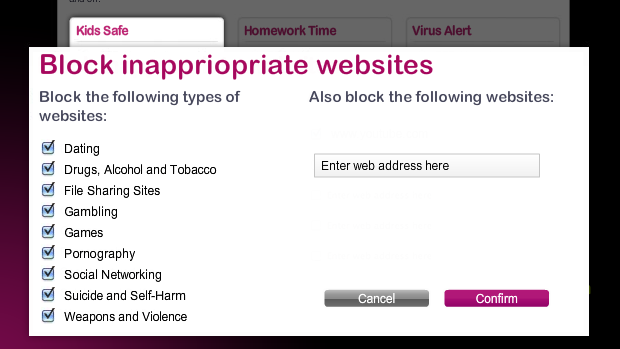

Deploying a configuration screen with one or more options pre-selected raises questions regarding how ‘free’ a choice this is, how considered users decisions will be, and how many will choose the alternative (unfiltered) option. The screen describing the filtering categories might look something like this:

We can shine light on this issue from research in many fields including psychology and economics, where choosing the default option is known as ‘status quo bias’ and regularly affects decision making. In policy-making circles, an awareness of how to use defaults to affect decision-making has been called ‘nudge’ - Sunstein & Thaler say this can be used to:

“...attempt to steer people's choices in welfare-promoting directions without eliminating freedom of choice”

How welfare-promoting these proposed Internet filters are, and how free peoples’ choices will be are the key issues.

N.B. Interested readers may wish to read ’Nudge and the Manipulation of Choice: A Framework for the Responsible Use of the Nudge Approach to Behaviour Change in Public Policy’

Status-quo bias and defaults in brief

Status quo bias can be explained as a cognitive bias towards the current state of affairs. From a rational perspective, when individuals are making decisions about various alternatives, only the preference-relevant features should influence their decisions (for example prospective car buyers choosing from a set of colours for their new car). But in reality, when a choice is labelled as the status quo it influences decision-making above what would be predicted.

A choice can be labelled as the status-quo or default in two main ways:

- Pre-selecting an option as the default

-

Referring to statistics regarding past majority choice

As discussed in the examples below, framing an option as the default greatly increases the chances that that option will be chosen, even when the option assigned to be pre-selected is random. This knowledge, coupled with a policy-maker’s agenda, could lead to a situation where a person is ‘nudged’ into making a particular decision. As Mandl and colleagues warn:

“A major risk of defaults is that they could be exploited for misleading users and making them to choose options that are not really needed to fulfill their requirements.” (pp. 19)

Examples from research - how defaults affect decision making:

Default choice

Perhaps the most well known example of default opt-in is that of organ donation. Countries who employ a default opt-in (presumed consent) scheme see average rates of 97.56% compared to countries who employ a default opt-out (explicit consent), where the average rate is 22.73%.

A similar pattern of behaviour can be seen in decisions relating to car insurance, healthcare plans, and internet privacy policies, where both defaults and the linguistic framing of options affect opt-in rates.

Interestingly, research has demonstrated that if people are given the option to delay making a decision, those who accept the delay (even 15mins) are less likely to choose the default.

Active choice

In comparison, giving people an active choice (nothing pre-selected as default) can lead to more beneficial outcomes. An active choice offers a seemingly free choice and appears to lead to decision outcomes which may be quantitatively and/or qualitatively desirable.

For instance, in one study 28% more employees chose to participate in a 401(k) savings scheme when they were given an active choice about whether or not to participate (compared to when the default was not to participate).

Interestingly, researchers have recently developed a concept called ‘enhanced active choice’ (EAC) which retains the concept of active choice, but adds language to certain options to make their associated risks more obvious. When testing out this theory, the researchers found that 75% (EAC) vs. 62% (active choice) agreed to get a flu shot. This concept was applied to healthcare, where the researchers argue that presenting patients with a default choice is likely unethical.

N.B. Interested readers may wish to read a ’Salvaging the concept of nudge’ which offers a defence of nudge in healthcare contexts.

Why people choose the default option

There tend to be three reasons why people choose the default option:

-

The default is seen as a suggestion/recommendation by the policy-maker. Additionally, if an expert opinion is sought and their bias is in the direction of the status quo, the decision is almost certainly to also be in that direction.

-

Making a decision involves effort, whereas accepting the default is effortless. Effort can be physical (filling forms, telephone, posting) or mental (weighing up alternatives).

-

Defaults often represent the existing state or status quo, and change usually represents a trade-off. There may be perceived risks associated with change, and people are loss averse (they experience losses more than equivalent gains).

What might this tell us about filtering choices?

Pre-selected

- Given the above evidence regarding default choices combined with the Government position, ‘asking’ (under threat of legislation) ISPs to implement default blocking, it seems clear that a large number of users will be nudged into choosing a filtered internet connection.

- Actual numbers are hard to predict and partially dependent on the actual design of the decision screen, but if we look at some comparable studies uptake may be as high as 89% (almost 9/10) of users being nudged into filtering their internet connection.

- In the case of parents this number may be even higher, dependent on the language used to describe the filters (see below).

Framing filters as ‘parental controls’

- For parents configuring their internet filter, if the filter is framed as a ‘parental control’ or suchlike which reminds them of their additional role (i.e. not just an internet user, but also a parent) it is likely to lead to greater risk aversion and therefore an increased choice of the filtered connection.

- Counterintuitively, this effect may also affect those adults who are not parents, but who well understand a parent’s role, although it could also be argued that such framing will clarify the intended target for the controls, leading to non-parent adults to infer that the filtered option is not designed for them.

- The psychological theory which speaks to this is called ‘priming’, where a person’s behaviour can be influenced by exposure to prior stimuli. Examples include priming people with words around a certain theme (e.g. happy/sad), describing or exposing them to certain behaviour (e.g. risky/careful), and reminding them of possible roles they could perform/parts of their selves (e.g. parent/daughter).

Different linguistic framing

- As mentioned in the examples above, linguistic framing of a problem and additional explanatory text can affect decision making. For example, with a default opt-in condition, phrasing in the positive or negative has been shown to affect users’ decisions

- If we assume the ISPs will use a pre-selected Yes/No choice, a comparable study design suggests that the ISPs could expect an uptake of up to 89.2% e.g:

![]()

- However, the ISPs could potentially attain an even higher opt-in rate (up to (96.3%) with a single unticked checkbox:

☐ Do NOT filter my internet connection

Closing thoughts

There seems to be a contradiction in what the Government wants. On the one hand it wants “...filters that are preselected to be on...”, and on the other hand it also wants “...parents aware and engaged in the setting of those filters”. But from what the research tells us about decision-making, these two desires seem to work against each other.

We know that defaults will cause more people to turn on their filters. But deploying defaults also will likely reduce how carefully people consider their options and engage with the issues. When launching this new policy, David Cameron said “One click to protect your whole home and to keep your children safe”, but this arguably encourages a ‘click and forget’ approach to parenting.

Although in the Prime Minister’s speech and in the Government’s earlier response, references are rightly made to education and the role of ‘digital parenting’, surprisingly there appears to be no mention of these issues in the proposed configuration screen. Given the importance of the decision, surely this an ideal place to signpost these issues. For example, why not include messages on the screen that will:

-

engage people in the complexities of the arguments e.g. pros and cons, how (overly) successful the blocking is

-

encourage those who are parents to consider the issues, start a discussion with their children about online safety, and empower them to manage risk

-

inform parents of the other options available to them such as device-based filtering

To quote Professor Tanya Byron, the clinical psychologist who authored one of the expert reviews commissioned by the Government over the past couple of years:

“Children and young people need to be empowered to keep themselves safe – this isn’t just about a top-down approach. Children will be children – pushing boundaries and taking risks. At a public swimming pool we have gates, put up signs, have lifeguards andshallow ends, but we also teach children how to swim”

N.B. Last week the Government released proposed amendments to the Consumer Protection Regulations (Unfair Trading) that would “ban pre-ticked tick boxes for extras that the consumer may not want or need”.

Ben Meghreblian has a background in psychology & IT and is currently working on a report for the Open Rights Group relating to internet filtering. His interests include psychology, human rights, technology, and science-related topics. He tweets @benmeg

Image: Internet censorship in Slovak by opensourceway CC BY-SA 2.0

The problem with #twittersilence

Catherine Baker gives her insight into why she decided to not partake in the #twittersilence movement.

My Sunday morning Twitter timeline has rarely been busier than on #twittersilence day, 4 August - and not just because the BBC was going to be announcing the next Doctor.

Receiving misogynistic abuse and intimidatory threats online is an everyday reality for many women, especially those who use the internet to talk about their experiences of being marginalised in society and to build solidarity with others. Over the weekend of 27/28 July, it became headline news in the UK after Caroline Criado-Perez, who had been campaigning for the Bank of England to commit to always including a female historical figure on its banknotes, spoke out about the rape threats she had received.

What followed was a week of debates, both on Twitter and in the mainstream media, about how to solve the problem - although the parameters of that problem could look very different depending on what information was reaching you.

The headline story was about the abuse being directed to a number of white cis women who were currently in the public eye, and the idea to solve it by installing a ‘report abuse’ button on Twitter.

Not in the headlines were many other women’s experiences of online abuse, particularly those of women who are also marginalised in other ways, such as being a woman of colour, trans*, a Muslim, or disabled. In positions like these, not only may you be receiving even more abuse, you’re also less likely to be believed. An abuse button, which could be misused by organised campaigns to shut down critical opinions, could harm you in ways that supporters of the idea who have more privilege may not have been able to see (this fear resurfaced last week when Twitter suspended the @transphobes account, which had been collating examples of transphobic speech on Twitter).

The links in the last paragraph give a much more complex picture of Twitter as a political space, though I’d argue they help to make that picture more precise and accurate - at least regarding the networks of users to whom #twittersilence meant anything. They also illustrate some of the questions that intersectional feminism is likely to raise and that other varieties of (white) feminism may be less likely to attend to.

Twitter’s functionality for users to disseminate links quickly to the people who follow them and for writers and readers to take part in two-way, publicly visible conversations has made it a place where these different worldviews come into fractious conflict. Two significant incidents in the last year, reactions to dismissive remarks by Caitlin Moran about race and to transphobic language by Suzanne Moore, did much to create a recent history of mistrust that fed into how #twittersilence was received.

The idea of #twittersilence as a protest against ‘trolls’ originated with a tweet by Caitlin Moran a few hours after the abuse button petition was launched.

I can’t write about #twittersilence without acknowledging that I was one of the people who chose not to take part (though I also respect the choices of the friends and colleagues who did). I had several reasons for that, some to do with the concept of silence as a protest, and others to do with how the events leading up to #twittersilence had been framed.

If abuse and threats are deliberately being used to silence women online, silencing oneself didn’t feel like an effective form of protest (and out of character with the idea of ‘shouting back’ that had already been raised as a response). I was uneasy, too, about the restrictive way in which online abuse had been being covered, as if it was only a problem now that white cis women in the media were complaining.

Framing the silence as a protest by the ‘pleasant people’ also has constraining implications for the idea of Twitter as a political space - as if the world is made up of pleasant people, trolls, and no-one in between. This would shut down whole traditions of angry expression by the oppressed, as Kat Haché points out in her critique of the expectation of ‘civility’, or as Audre Lorde observed in her classic essay on ‘The Uses of Anger’, which made the case that the anger of women of colour against racism could, ‘focused with precision [...] become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change’.

A further problem for me was that, in Twitter’s recent history, some women writers criticised on Twitter for racism or transphobia have described that as part of the abuse they receive. The language of these criticisms is often angry, yet the motivation, and the power relations, behind them, seem very different to the threats men have been directing at women in order to stop them talking. ‘Why should it be my responsibility to be polite to people who believe that I am a deception[?]’, asks Haché, rejecting the argument that she should show civility towards people who deny her right to exist as a trans woman. Indeed: why should it be?

Twitter is sometimes compared to London’s 18th-century coffee-houses as a conversational forum for public opinion. It’s more like one single coffeehouse of infinite size, where everyone can overhear and try to take part in almost any other conversation. Its speed and scale create new kinds of questions: is it responsible for a celebrity user to retweet messages from members of the public who disagree with them? Are there times when repeated speaking out by users from a marginalised group can give the appearance of a ‘mass minority’ when the power dynamics haven’t really changed? The ethics of Twitter as an instant political space are still to be established. To fulfil the hopes that many of its users have in it, however, it will need to accommodate as diverse as possible a range of tactics, styles and values of activism, with awareness that the simplest solutions may hurt those who benefit from Twitter most.

Catherine Baker works as a lecturer in Hull and has been active on Twitter since 2010. The views expressed here are her own and do not speak for her department or her university.

Image: Follow me on Twitter! by Slava Murava Kiss CC BY-NC 2.0

The Right to Open Access to Humanities and Social Science Research

Ernesto Priego looks at initiatives to increase public access to academic work and research data.

Open access refers to the free access to and reuse of scholarly works. Peter Suber, who was the principal drafter of the Budapest Open Access Initiative (February 2002), and authored the book titled Open Access (2012), defines it as academic literature which is “digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions.”. Creative Commons remains the leading organisation in the development of open licenses that provide a social and legal framework to works that are openly available. Being digital, online and free of charge, open access scholarly outputs require open licenses that ensure their reuse within specific parameters determined by the licensor.

It was also in June 2012, ten years after the Budapest meeting, that the report from the National Working Group on Expanding Access to Published Research Findings (led by Dame Janet Finch CBE) published their report, titled 'Accessibility, sustainability, excellence: how to expand access to research publications' [PDF]. The report made recommendations to improve open access to academic works from the UK, and the Government announced on 16 July 2012 that it had accepted the recommendations looking to the Funding Councils and Research Councils to further develop their existing policies, some of which had been in place since 2005.

It is no coincidence that the Government’s response to the Finch Report was issued at the same time as their Open Data White Paper, which led to the establishment of a Research Transparency Board in order to develop policies to increase public access to research data. Like the Open Access ‘movement’ itself, most of these proposals originated from a conception of research that identifies it with ‘science’, but not necessarily to the arts, humanities and social sciences (e.g. the Royal Society’s Science as an Open Enterprise report).

A series of Open Access policies have followed these events, such as Research Councils UK’s Open Access policy (announced 16 July 2012), coming into effect for all research articles submitted for funding from 1 April 2013. The Higher Education Funding Councils (HEFCE) also got their gears in motion for developing proposals to ensure that research works submitted to the Research Excellence Framework (REF) or similar assessment exercise after 2014 are as widely accessible as possible; initiating a consultation with their partners in research funding and other interested parties. The European Union Commission also published new policies [PDF] both for open access to publications and for access to research data resulting from projects funded under Horizon 2020 (coming into effect in 2014).

This series of announcements and policies have created a great deal of anxiety and confusion amongst researchers. The Finch Report suddenly shook several sectors of academia that had not considered open access publishing before, or that work in fields where ‘data’ is a foreign language, or where the traditionally accepted outputs are not necessarily journal articles but monographs. It is possible that for many researchers in the arts, humanities and social sciences the notion of sharing research outputs openly through Creative Commons licenses was unheard of. In the UK, the editors of 21 history journals, for example, issued an open statement in December last year opposing to using so-called ‘free culture’ licenses, stating they would only use CC BY NC ND (Creative Commons Non-commercial Non-derivative) licences only, and explaining that in their opinion less restrictive licenses meant that “commercial re-use, plagiarism, and republication of an author’s work will be possible”.

A similar opinion was expressed by six academics in the letters page of the London Review Books (24 January 2013), stating that the use of Creative Commons Attribution licenses “would seriously undermine the integrity of the work scholars produce,” suggesting that more permissive open licenses that allow reuse of research outputs are a threat to “academic freedom, the international standing of UK scholarship and intellectual property rights.”

There are still many questions, fears and interests of all sorts defining the current debate around open access outside STEM fields. Funding allocation works differently across fields, and in spite of recent policies for many scholars funding to publish in ‘Gold’ Open Access publications that rely on Article Processing Charges remains a distant dream. In combination to varying degrees of confusion about copyright and the perceived dangers of openness, we are far from seeing a general consensus on how academics should embrace the values of Open Access.

Some academics feel they are being ‘bullied’ into Open Access, forced to share outputs through methods they feel might jeopardise their career prospects. Perhaps this is the most important case that Open Access advocates need to make: the urgent transformation of the traditional systems of assessment and promotion, that were defined in times in which transparency, openness, wider access and nearly-instant dissemination channels did not exist. These are strange times indeed when some junior academics feel they need to fight for what they perceive as their right not to publish open access (even sometimes when they’ve been funded by the taxpayer or by funders with Open Access policies). It is my personal belief that Open Access advocates are fighting for the right of others to access research that had traditionally been paywalled from the general public, and for the right of scholars at all career stages to ensure their work has more prospects of getting disseminated and eventually, luckily, more widely read, cited and ‘reused’.

Those of us who believe that Open Access is about ensuring wider and fairer dissemination and construction of knowledge, across borders and without paywalls for those who should most benefit from it (learners and readers, regardless of who or where they might be) need also to work harder at empowering graduate students and Early Career Researchers to opt for Open Access publication platforms by collectively working towards a positive transformation in academic culture, one where open availability of online scholarship is not considered a liability but a desirable asset.

As promised, in February 2013 HEFCE made a call for advice on developing the four UK funding bodies’ joint policy on open access in the post-2014 REF, and on 24 July 2013 they followed it up by launching an online consultation inviting “responses from higher education institutions and other groups, organisations and individuals with an interest in scholarly publishing and research”. (Read the consultation here). This is an opportunity for the UK academic community to exercise their right to have their say—before it is definitely too late.

Ernesto Priego is Lecturer in Library Science at City University London.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of his employers or colleagues.

Sleeping with the enemy

Wendy M Grossman looks at the Home Office's attempts at trying to keep its citizens informed via social media.

Sometime in the mid-1990s, when the barrage of daily postal mail was at its height, I started suggesting to PR people a campaign to send out all press releases on the backs of postcards. The suggestion was not well received, so I smirked a little when PR people started posting headlines and links on Twitter.

Dealing with government press people was always a different experience, however. They were far less likely to be sending you screeds of (mostly) unwanted paper or phoning you to ask if you'd read them, and much more likely to be the obdurate wall between you and the person you'd like to talk to. I recall the Home Office as the most difficult: you'd never get past the press desk, and what you'd eventually receive, in answer to the list of questions you were forced to submit, was a couple of anodyne quotes attributable only to "a government spokesman". Hence, I think, the aggressiveness of the British press when they did get a chance at these folks – I say aggressive, Conrad Black, as his former employee Ben Rooney (@benjrooney) pointed out on Twitter this morning, says destructive and irresponsible. I figure it's the same frustration that leads a driver to cover a few hundred yards of city street at 50mph after being stuck in a traffic knot for ten minutes. Your best shot was (and is) to grab these people when they spoke at conferences.

Yesterday's edition of tea camp, the monthly meetings that pull together dozens of digitizers from all parts of government, featured a varied discussion of what that's meant for government press teams. Twitter accounts. Facebook pages. DEFRA has a tumblr on how they're tackling bovine tuberculosis, run by one enthusiastic person.

"We don't have press releases any more," said Christina Hammond-Aziz (@hammondazizsays), from the Food Standards Agency. Instead, they have Web stories, which anyone can read or subscribe to via RSS, and as not-different as that sounds, it's an improvement over the situation that prevailed for a while, which had one team writing a press release and another writing a Web story that linked to it.

On the one hand, you have to applaud initiatives that so clearly widen the range of people these communications teams will engage with. It's surely right that you shouldn't have to be a journalist on a national newspaper (or an academic expert answering a formal consultation) to be able to engage directly with the people in charge of making and communicating policy.

On the other…take this quote, from Stephen Hale (@hmshale), head of digital for the Department of Health: "The press team at the Department of Health is brilliant at what they do. They're a crack team – they can quieten down or amplify a story if they need to." And this one, from Penny Fox (@wonderlanded), deputy head of news and digital at DEFRA: "We have ten Twitter accounts solely about policy." Her colleague, Verity Hambrook (@verityhambrook), re the policy team: "[they] can use their account to target the right group of people."

I like the idea that engagement with those genuinely interested in government policy is widening out and becoming more flexible. But – and this was the question I asked – do these many different forms of engagement feed back in the sense of recanting when the response clearly shows the policy is wrong? The answer – from whom I'm not sure now – was yes. Instead of just doing ordinary 12-page PDF consultations, they do SurveyMonkeys, and the results of those and follow-up discussions feed back into new SurveyMonkeys. Throughout, they make sure the policy teams are aware of the criticisms they're getting.

Today, as if by magic, along came what could prove to be a very good test: the Home Office (@ukhomeoffice) has been boasting by tweet about sending out UK Border Authority agents to tube stations to spot-question people they think might be illegal immigrants and the 139 arrests it's made (there's also a press release - er, Web story. As myriad twitter responses point out, such questioning is not only racist but illegal. Under section 31.19 of the Home Office's own guidelines (PDF), immigration officers must have information that "constitutes reasonable suspicion" and questioning must be consensual; they do not have the power to compel someone to stop or answer questions and they have no power to arrest you if you walk on and ignore them. I am a foreigner myself, and although (white, 59, female) I'm hardly likely to be stopped, Britain today suddenly seems less of a safe place for me to live. The operation offended even the UK Independence Party, quite possibly the people it was supposed to impress.

If the notion of feedback into policy has any meaning, the Twitter storm should make the Home Office stop, check with its lawyers, apologize, and change behavior. Let's hope the behavior the Home Office changes is less its club-footed use of Twitter and more its treatment of ordinary people going about their daily lives.

Wendy M. Grossman’s Web site has an extensive archive of her books, articles, and music, and an archive of earlier columns in this series. Stories about the border wars between cyberspace and real life are posted occasionally during the week at the net.wars Pinboard - or follow on Twitter.

Latest Articles

Featured Article

Schmidt Happens

Wendy M. Grossman responds to "loopy" statements made by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt in regards to censorship and encryption.

ORGZine: the Digital Rights magazine written for and by Open Rights Group supporters and engaged experts expressing their personal views

People who have written us are: campaigners, inventors, legal professionals , artists, writers, curators and publishers, technology experts, volunteers, think tanks, MPs, journalists and ORG supporters.